On the Wrong Side of History

Towards a New Approach to Ostalgie Cinema

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Astafeva, Tatiana: On the Wrong Side of History: Towards a New Approach to Ostalgie Cinema. In: Research in Film and History. New Approaches (2021), pp. 1–21. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/15779.

Introduction

The phenomenon of ostalgie1 appeared in the 1990s and manifested itself predominantly in literature, entertainment, and commercial (mostly tourist) spheres. The proliferation of the so-called ostalgie wave coincided the critical discussions of Spaßgesellschaft and consequently ostalgie was approached as a noncritical romantization of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Ostalgie films, therefore, were produced in the context that regarded the phenomenon as regressive: the conceptualizations of ostalgie in film studies for the most part inherited the points of critique that were addressed in the first discussions of ostalgie novels, Ossi-parties, and Trabi safari. Mary-Elizabeth O’Brien acknowledged a moral aspect of the debates that saw the phenomenon as a device for simplifying the GDR past: “[ostalgie is regarded as] irresponsible, because it failed to recognize the GDR’s human-rights violations and the suffering of its victims”.2 Following the interpretations that see the phenomenon as “at best a naive sentimentalising and at worst an intentional banalising of the GDR past”,3 ostalgie films are criticized for reducing the German history in its complexity to simplified characters and stereotypes.

Less critical approaches consider ostalgie cinema to be an oppositional memory about the GDR past. These conceptualizations echo the understanding of ostalgie phenomenon that Aleida Assmann suggested in her analysis of German memory culture after reunification:

While today the GDR is officially condemned as a state with no rule of law (Unrechtsstaat), it lives on in people’s memories as an important phase of their biography and identity. The abrupt and sweeping devaluation of the half if not the whole life leads to the oppositional memory, so-called “ostalgie”.4

Therefore, according to Thomas Ahbe, it functioned as a “communicative praxis in which memories are dealt with, processed — not repressed, denied or concealed”.5 In this line of thought, ostalgie films were opposed to those that dealt with the reflections on the Stasi legacy, like DAS LEBEN DER ANDEREN / THE LIVES OF OTHERS (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, 2006), that aimed to give back the critical sight on the GDR.6

With more focus on the cinematic peculiarities of ostalgie, some studies explore the phenomenon through its embodiment in the realm of material culture. These approaches, for the most part, derive from the understanding of ostalgie as a counter-memory, seeing the material culture and everyday life as the only possible realms for addressing nostalgic longing for the GDR. In many ways, such examinations follow nostalgia cinema’s critique of Fredric Jameson and inherit accusations in the idealization of the past and understand ostalgie films as a regressive phenomenon. For Jameson, the nostalgia film style is attained through intertextuality — the effect of the “connotation of ‘pastness’” — reorganizing the past images into the form of a pastiche, symptomatic of the postmodern crisis of historicity. Being a romanticized stylization, nostalgia cinema was criticized by Jameson for possessing a “pseudohistorical depth, in which the history of aesthetic styles displaces a ‘real’ history”.7 In this vein, according to Jaimey Fisher:

Ostalgie seems, indeed, to confirm Higson’s and Koepnick’s critiques of nostalgia in heritage cinema that tends to preserve a fantastical past via fetishized, museum-like mise-en-scène. If Ostalgie served the useful purpose of reminding audiences of everyday life in the GDR — an everyday life that may have intermingled with but also outstretched conventional politics — there is a sense, looking back now from a post-2000 landscape, that films like Sonnenallee, Heroes like Us, and even Good-Bye, Lenin! went too far in recuperating the GDR, often by obscuring the suffering caused by the state.8

Being analyzed in the context of the post-reunification German film industry, ostalgie films are seen as part of the general commercialization of the cinema in the 1990s. In this vein, cinematic versions of ostalgie are regarded to be a mere marketing strategy or fetishization of the GDR past, a “lucrative industry (for retailers and television and film producers alike)”9 that tends to create an appealing image of the past and as a result lacks any critical reflection.10 In the same way, films are labeled ostalgic for marketing purposes to refer to their (mostly failed) attempts to reproduce the commercial success of Thomas Brussig’s SONNENALLEE (1999) or to copy the peculiarities that made Wolfgang Becker’s GOOD BYE, LENIN! (2003) popular. This labeling, then, indicates that ostalgie cinema is contextualized as an industrial process, or a production trend in terms of Tino Balio,11 but it has not been clarified what exactly constructs an ostalgic quality, or essence, of a film.

To sum up, studies on ostalgie films explore the reception, cultural significance, or ideological potentials of ostalgie cinema extracted for the most part from a narrative analysis. Ostalgie cinema is connected to the context of the German memory culture and understood as a “falsifying” form of memory. Another remarkable peculiarity is the prevalence of two ostalgie films as material for case studies: although a cinematic ostalgie wave is mentioned in many papers, GOOD BYE LENIN! and SONNENALLEE are still almost the only examples of ostalgie cinema that are analyzed.12 Further, the role of aesthetics is reduced to the analysis of the everyday material culture or, rarely, retro aesthetics. The approaches that see ostalgie film as a set of iconic commodities do address to some extent the visuality of the phenomenon. Nevertheless, they do not explain why these particular commodities in some cases exclusively contribute to the construction of a certain historical period and in others facilitate the ostalgic quality of a film.

The article starts with an assumption that ostalgie film must be assessed beyond the discourses of historical accuracy and dismissive critique that the phenomenon of ostalgie cinema inherited for the most part from the ostalgie TV shows and other manifestations of nostalgic longing for the GDR in popular culture and commercial sphere. I argue that the emphasis on the sociocultural level of ostalgie can be enriched with potentially significant meanings of the phenomenon in cinema. Next, I introduce an interdisciplinary phenomenological approach, based on the understanding of nostalgic historical experience by Frank Ankersmit. I argue that this approach can be helpful in the critical analysis of emotionally and aesthetically charged cinematic phenomena like ostalgie. In this case, it is not so much “nostalgia triggers” but rather a nostalgic historical experience produced on both narrative and aesthetics levels and conceptualized as an experience of distance13 that can be regarded as a core of ostalgie films. Further, an exemplary analysis of the film KUNDSCHAFTER DES FRIEDENS / OLD AGENT MEN (Robert Thalheim, 2017) is provided that is based on the above-mentioned approach. Finally, in the conclusion, the essay discusses how the analysis of the specificity of ostalgie films can contribute further to a more complex understanding of German films about the GDR past.

Nostalgic Historical Experience

Following the debates within social sciences about the nature of historical knowledge and its methodology in the 1970s, the analytical philosophy of history has been gradually supplanted by narrativism. Frank Ankersmit in his book Narrative Logic. Semantic Analysis of Language of Historians (1983) followed this shift by proceeding from Hayden White’s tropological critique of explanatory historiography and claiming that history is constructed exclusively through the narrative, which is formed by rhetorical tropes. Already in 1994 in his work History and Tropology: The Rise and Fall of Metaphor Ankersmit had expressed not only his own critique of narratology but also acknowledged a general crisis within the narratological methodology.

The main line of criticism articulated by Ankersmit was to question the equation of the past with the historical narrative, which in turn would eliminate any discrepancy between the present and the past:

Since the actual past is only an argument and is never conclusive in settling historiographical debate, the idea of a correspondence between a historical narrative and the actual past will get us nowhere if we want to understand the narrative writing of history. […] Whether we see historical narrative as a conjunction of statements or as a whole, in neither case can we meaningfully speak of a correspondence between historical reality and historical narrative.14

In this context, Ankersmit introduces the phenomenon of nostalgia from a phenomenological position through the concept of “historical experience”.15 For Ankersmit, nostalgia is “the strongest form of memory”16 that deals with the longing for the past as something that is missing and cannot be returned, but can be grasped as an experience of distance17 between the present and the past. Nostalgic historical experience, nevertheless, is not an entirely affective Nacherleben (reliving) of the past in the sense of Dilthey and Rickert; for Ankersmit, an experience of the past18 is not possible, but rather in nostalgia the unattainability, the distance of the past, comes to the fore. In the moment of nostalgic historical experience, the past is realized as “breaking away from the present”19 and the present is “suddenly relegated to the periphery”.20 In other words, the past and the present are simultaneously interconnected and detached from each other in nostalgic historical experience — the past comes to the fore but for the experience of distance to happen one should realize oneself in the present:

Nostalgia gives us the unity of the past and the present: for, the experience of difference requires the simultaneous presence of what lies on both ends of the difference, that is, of both the past and the present. In the experience of difference, the past and the present are united. However, they are both present only in their difference — and it is this qualification that permits us to express the paradox of the unity of past and present. But in both cases, whether we prefer to see nostalgia as the experience of difference or as the unity of past and present, difference becomes central while the past and the present themselves are reduced to mere derivative phenomena. The past no longer is the “real” object it was for historism. The “reality” experienced in nostalgia is difference itself and not what lies at the other side of the difference — that is, “the past” as such.21

It may seem that the focus on the rupture between the past and the present that Ankersmit writes about indicates similarity of the conceptualizations of Ankersmit and Svetlana Boym as the core of nostalgia.22 But I would argue that Ankersmit’s historical approach to nostalgia not only essentially differs but can be more fruitful for the analysis of cinematic manifestations of ostalgie. Svetlana Boym introduces two types of nostalgia: restorative, which “engage[s] in the antimodern myth-making of history by means of a return to national symbols and myths” and “manifests itself in total reconstructions of monuments of the past”,23 and reflective, which is focused “not on recovery of what is perceived to be an absolute truth but on the meditation on history and passage of time”.24 These types, or rather tendencies that may overlap,25 differ in their relation to the distance between present and past: restorative nostalgia tries to eliminate this difference and actually reestablish the past, whereas reflective nostalgia is based on this distance and cherishes it. What Ankersmit describes as nostalgic historical experience may seem to correspond reflective type of nostalgia in Boym’s theoretical considerations.

In this line of thought, for Ankersmit, restorative nostalgia as described by Boym is not possible at all, or it would be something other than nostalgia, as far as it corresponds with the historical experience in the sense of Collingwood, Dilthey, and Rickert — a “reliving” or “re-enactment” of the past — whereas Ankersmit agrees with Huizinga in that the past cannot be “relived” but should be realized as unattainable. Ankersmit addresses this essential difference and points out the a-historicity of the restorative type of nostalgic longing.26 Moreover, if one tries to apply this approach to film analysis, restorative nostalgia will encompass every historical film that is made with attention to details and that is dramatic in its mode.

Following the overall debates in historical science, Ankersmit connects nostalgic historical experience to the realm of memory. For Ankersmit, nostalgic historical experience does not refer to the concept of “historical truth” but rather operates within the realm of “authenticity.” Nevertheless, for Ankersmit, individual or collective memory should not necessarily precede nostalgic historical experience; nostalgia is opposed to big historical narratives and reminiscent of aesthetic experience that is also open to those who have no previous experience of this past. Further, whereas for Svetlana Boym nostalgia is a historical emotion — a purely affective phenomenon — for Ankersmit nostalgic historical experience is both affective and cognitive: in authentic nostalgic experience, the sensing about the past (atmosphere derived from particular everyday moments, small objects, habitual events) confronts the knowing of the past occurring in the present moment (big historical narratives):

We must observe that the events in our personal history that may trigger a nostalgic yearning are only rarely, and certainly not necessarily, the kind of events we hold to be of great significance in the story of our life. Thus we may nostalgically recall a certain atmosphere at a quite specific moment in our parental home or a holiday with our family; but we will seldom have nostalgic memories of having passed a particular examination or of having been promoted to a more responsible position.27

Nostalgia is a very affective relation to the past, and, in regard to cinema, its imaginative and sensitive essence can, therefore, be best grasped with the help of a phenomenological approach.28 The following film analysis aims to show how Ankersmit’s historical theory can provide the basis for an approach to ostalgie cinema combined with film studies theories.

Ostalgie and Its Quest for Historical Continuity

Unlike most ostalgie films, which thematize the fall of the Berlin Wall,29 OLD AGENT MEN takes a temporal distance from the GDR — it is set in 2015. Nevertheless, the article argues that ostalgic historical experience is possible even without direct situating of the plot during the GDR era.30 Indeed, the film OLD AGENT MEN effectively exploits this temporal distance of more than twenty-five years since German reunification to accentuate its ostalgic quality and allows for a more overt dealing with the GDR than most historical films primarily set in the past offer.

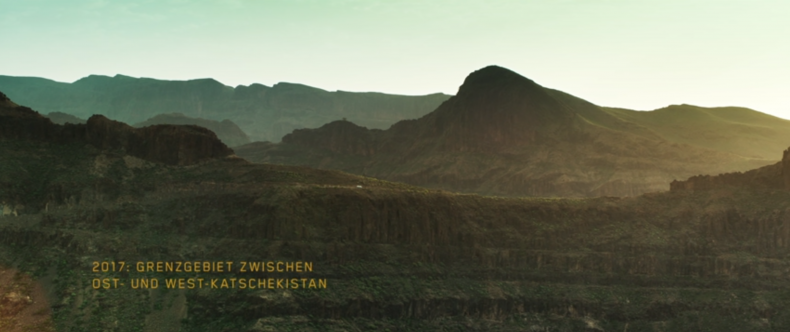

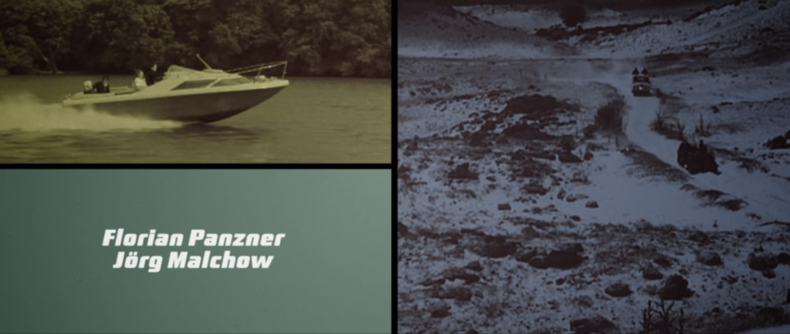

The departure point of the film is an almost hopeless assumption that the former East German secret agents may help solve current problems of the Federal Intelligence Service (BND — Bundesnachrichtendienst). Four retired ex-colleagues — Jochen Falk (Henry Hübchen), Jaecki (Michael Gwisdek), Locke (Thomas Thieme), and Harry (Winfried Glatzeder) — are called back on duty because only they have the relevant experience and knowledge to ensure a peaceful future for the divided republic of Katschekistan, an imagined former Soviet state. Starting with such an emblematic setup, OLD AGENT MEN employs plot and iconography to ensure its identification with an espionage genre. On the narrative level, the secret mission of rescuing Katschekistan drives the entire story of the film to unfold further in the form of a quest. On the audiovisual level, the film states its belonging to the espionage genre already in the teaser (fig. 1)31 and the opening sequence, which shows shots from action films of the 1960s in a split-screen technique (fig. 2) accompanied by a soundtrack typical for this genre:

The track with the title Old Agent Man begins like the Kraftwerk classic Trans Europa Express and is reminiscent of the golden days of crime and espionage films. The deep voice, the 60s organs, and the dramatic brass arrangement could be created for a James Bond film like Goldfinger.32

OLD AGENT MEN goes even further, teasing its (feigned) seriousness towards belonging to the espionage genre in one of the first dialogues about the protagonist Falk between two BND agents: “So this is him, the James Bond of the [East German] zone… It’s not surprising the [GDR] state collapsed”.33 The phrase confirms the film’s parodying nature and likewise indicates the reference to espionage films about GDR secret agents. Namely, the aforementioned opening credits and theme music refer to the TV series DAS UNSICHTBARE VISIER / THE INVISIBLE VISOR (Peter Hagen, 1973–1979), which was popular in the former GDR. The series was produced by the state-owned film studio DEFA in cooperation with the Ministry of State Security (Staatssicherheitsdienst – Stasi) and told a story of an East German secret agent, Werner Bredebusch (Armin Mueller-Stahl), who fought (and — needless to mention — always won) against his West German rivals. The popularity of the series is based on the fact that it borrowed “structures of the Western genre films and TV productions, which from the point of view of the SED ideologists were charged with politically reversed messages”.34 The parodic essence of the film contains, therefore, two layers: it is a parody of espionage films from the GDR that themselves make for a parody of Western-made espionage films. In terms of Henryk Markiewicz, OLD AGENT MEN is a parody sensu stricto — the one that “ridicules its model” — and THE INVISIBLE VISOR is a parody sensu largo, an “imitative recasting”.35 Hence, the film is perceived as a parody, both for viewers who are acquainted with the GDR espionage films and for a broader public — albeit on different levels.

A parody, often understood as a critical ideological debunking of constitutive generic elements, such as “[f]amiliar conventions, representational devices or modes of discourse”,36 in OLD AGENT MEN functions in a different register, as a self-conscious celebration of the object of its mockery, a “comic, yet generally affectionate, and distorted imitation of a given genre”.37 This kind of parodic register contributes to the production of ostalgic historical experience in OLD AGENT MEN. Firstly, the reference to espionage films thematizes, or puts the focus on, the GDR past (including its film heritage), in a very affectionate parodical mode. Secondly, this parody is simultaneously charged with irony, which is applied as a rhetorical strategy that on “the semantic level […] can be defined as a marking of difference in meaning or, simply, an antiphrasis”.38 On the one hand, the parodic register of OLD AGENT MEN requires the engagement with the previous cinematic experience and securely moves within the familiar generic narrative and aesthetic signifiers: that is, they affect viewers’ expectations and moods and in doing so “establish a sense of continuity between our cultural past and present”.39 On the other hand, the ironic tonality of this parody, to sum up, creates a necessary critical distance on formal (genre), aesthetic (generic iconography), and verbal levels. In OLD AGENT MEN, irony is a rhetoric device that both makes for a parody and engages with discursive politics of ostalgic historical experience.

Whereas films of various genres are labeled as “nostalgic”,40 the modality of most of them, adopting Christine Gledhill’s theory (2000), is usually melodramatic.41 For the most part, the nostalgic quality is prescribed to the narrative dominated by the sentimental look back to the pasts that are showed as better places. Their driving force is dissatisfaction with the present, which results in a longing for an idealized past, often with a bittersweet sadness, dramatized on the aesthetic level with slow-motion sequences.42 Being conceptualized as a genre, a cyclic concept that is constantly changing its interpretations and conventions over time,43 ostalgie film is, on the contrary, in most cases a comedy. Further, following Svetlana Boym, it can be assumed that irony in the case of such an ostalgie film as OLD AGENT MEN might be a conscious choice of the comic device because in the postcommunist countries it “has persisted as a kind of identity politics […] in a world where everything has to be translated into media-friendly sound bites”.44 In the film, irony becomes a necessary filter that accentuates objects of ostalgic longing: everyday life and personal recollections are contextualized ironically, whereas authority and the political system are discussed in the register of more critical jokes.45 This ironic estrangement in the film indicates the reflective, critical essence of ostalgic historical experience in OLD AGENT MEN.

In their rescue mission, the protagonists are accompanied by the young Federal Intelligence Service agent Paula Kern (Antje Traue). A mission that the protagonists are supposed to accomplish together is a plot-building technique characteristic of espionage films, but in this case, it was also used to explore, contest, and negotiate the GDR past, as well as to produce ostalgic historical experience. Instead of introducing a romantic subplot with a Bond girl, which would be more traditional for the espionage genre, the film substitutes this generic convention with a generational conflict — Paula is half the age of Falk and could in fact be his daughter. The protagonists travel to Katschekistan and during their journey they face various situations that sharpen the differences between them. The conflict unfolds through narrative and aesthetic collisions between the former East German secret agents and Paula, confronting the knowledge about the GDR (of Paula) with the subjective experience of living in the GDR (of the four former secret agents). These collisions occur throughout the film and emphasize the distance between then and now, communism and democracy, analogue and digital, the past and the present, history as narrative and authentic historical experience.

The authenticity of the historical experience is an essential quality of ostalgie. It is primarily achieved through the subjective perspective of verbal nostalgic reminiscences, often of one of the protagonists.46 Whereas in nostalgia films reminiscences are bound to sentimentally charged recollections from childhood or youth, in ostalgie films they show very specific moments in the past that are predetermined by particular historical, and political, frames — the state system of the GDR. OLD AGENT MEN presents right away four different kinds of experience and, consequently, memories about the former GDR: that of Falk, who seems to have largely come to terms with German reunification, Jaecki, who still regrets the failure of the communist state, Locke, who has fitted perfectly into the free market economy, and Harry, whose life has not really changed. According to Ankersmit, the “discourse of memory recognizes that we can never appropriate them and that each attempt to do so would be ‘inappropriate’”.47 In other words, a viewer will never make these memories his or her own but will be able, due to their reliability and affective essence, to empathetically co-experience the distance that is made evident by them.

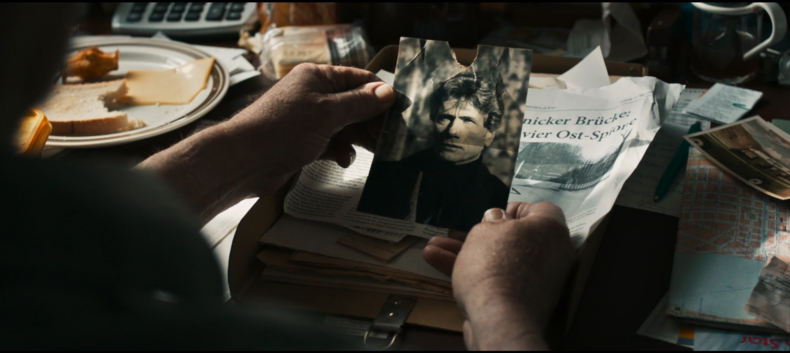

For Ankersmit, nostalgic historical experience, due to its affective intensity, has an episodic, fragmentary quality. In OLD AGENT MEN, this is achieved by the aforementioned verbal reminiscences as well as by visual interruptions in the form of archival photos. These archival photos have two functions in the film. In the first group are archival photos that come naturally as an element of mise-en-scène (fig. 3). Their aim is to illustrate the narrative. In the second group are archival photos shown in split-screen technique that suddenly disrupt the visual imagery and narrative of the film (fig. 4). They depict scenes from the everyday lives of the protagonists or products like a Soviet Moskvitch car, shoes, or other products widely associated with the GDR. The archival photos from the second group appear suddenly on the screen, they interrupt the narrative, the dialogue is muted at these moments and the theme music accompanies them. These fragments, as Jaimie Baron puts it, “exceed the homogenizing force of grand narratives by grounding themselves in the contingent and unruly ‘real’”.48

They depict everyday products and personal moments that may seem unimportant both for the protagonists and for the plot development as well. As was mentioned in the introduction, the thesis that ostalgie manifests itself mostly in the realm of everyday life and consumer culture was for a long time regarded as a consequence of the impossibility of talking nostalgically about the GDR in public discussions: political and social topics connected to the GDR were laden with problems such as state atrocities, that is why everyday culture has become the only realm to express nostalgic longing for. I would agree that ostalgie indeed can be regarded as a manifestation of the claim for a variety of narratives about the GDR. Nevertheless, departing from the understanding of nostalgic historical experience suggested by Ankersmit, nostalgia is essentially directed at small, seemingly insignificant fragments of the past:

We must observe that the events in our personal history that may trigger a nostalgic yearning are only rarely, and certainly not necessarily, the kind of events we hold to be of great significance in the story of our life. Thus we may nostalgically recall a certain atmosphere at a quite specific moment in our parental home or a holiday with our family; but we will seldom have nostalgic memories of having passed a particular examination or of having been promoted to a more responsible position.49

Therefore, in OLD AGENT MEN, ostalgic historical experience focuses on the everyday, small fragment of the past and in this way confronts the “homogenizing force of grand narratives”50 and “feeling of the past”: “Their magic lies in their partiality, which emphasizes their metonymic relationship to a whole that is gone forever and whose traces are also flickering their last”.51

During their mission, the protagonists visit places in Katschekistan where they worked together back during the GDR era. These places — their former secret headquarters hidden in the basement of a public swimming pool, a bar where they spent their evenings together — do not appear to represent a “lost home,” a utopian symbol of nostalgia in Heimat films.52 In OLD AGENT MEN, the temporal manifestation of ostalgie is rather carried out through the spatial dimension: in these places, the “past thus becomes locally and spatially present”,53 albeit not in the sense of a memorial but rather as a place that triggers memory, but more inexplicitly than “artificial” forms like rituals and museums. These places, thus, contribute to the tactile quality of nostalgic historical experience. Furthermore, these mise-en-scènes, a key element in the production of “pastness” in historical films, is of an unusual character in OLD AGENT MEN. Whereas many nostalgia films operate within a very detailed portrayal of an idealized past in that they use a very glossy retro setting54 like in the aesthetically elaborated films of Wes Anderson55 or heritage films,56 ostalgie attains nostalgic historical experience with the help of a completely reverse aesthetic register — aesthetics of decay. The places that give rise to ostalgic reminiscences of the protagonists are ruined, abandoned, forgotten — they are embodying the loss (fig. 5–6). The GDR past is constructed through almost vanished landscapes which sharpen the presence of the past and in doing so produce the experience of distance between the present and the past that is irretrievably gone. Unlike scrupulous recreations of mise-en-scène in historical and most nostalgia films, these traces of the GDR past are fragmented and necessarily contextualized, with a voice-over reminiscing about their everyday experiences in that particular place that the viewer simultaneously sees on the screen as “ruined,” or contrasting action sequences and ostalgic moments by suddenly pausing the fast soundtrack and letting the viewer (and protagonists) contemplate the abandoned landscapes in silence.

In contrast to the idealized glossy gloriousness of retro aesthetics, the “decay” look of the fragments from the GDR past within ostalgie cinema suggests its probable urge for authenticity of the historical, aesthetic as well as cinematic experience and adds to the subjectivity of the past represented on the screen. These places obtain this affective power and create an “authentic” nostalgic atmosphere,57 making the GDR past more tactile, more material and contributing to the “haptic visuality” of the film experience.58 Through this authenticity, aesthetics of decay confront a personal, subjective past with big narratives of political history from the present and in this way makes nostalgic historical experience possible on the screen.

The mission of the protagonists resolves in the glorious rescue of the imagined Katschekistan. The narrative and aesthetic collisions of the old and the new, communism and democracy, analogue and digital, the past and the present — these tensions recycled clichés and ridiculed stereotypes about the former GDR and were settled in a balanced liaison of experience and knowledge. For Ankersmit, nostalgic historical experience is fragmented, it lasts only a short period; in a normal situation, it should inevitably end. To quote Keith Jenkins’ study on Ankersmit, it is important to “place the past where it categorically belongs — behind us” because “the past isn’t something we should nostalgically dwell in or on, but something we should get out of, not least by stressing the positive aspects of ‘sublime’ experience”.59 Due to its setting in the present time, the film OLD AGENT MEN begins with the premise that all the protagonists found their place in German society after reunification; this ostalgie film, therefore, begins from a safe ideological position that nostalgic longing was caused not by the protagonists’ traumatic dissatisfaction with the present and a desire to relive the GDR past. Just as in Ankersmit’s line of thought, the ostalgic experience of distance, according to the film OLD AGENT MEN, made the otherness and unattainability of the past visible. The film ends with the sequence where Paula receives the genetic paternity test but decides not to open it and to have two fathers — Falk from the GDR and Frank Kern, a secret BND agent. This way, the ostalgic longing remains just a fragmentary experience that allows one to “be(come) what one is no longer”:60 through nostalgic historical experience, the past becomes a part of the present identity.

Conclusion

Ankersmit’s approach to nostalgic historical experience can be productive for the analysis of cinematic manifestations of ostalgie as it respects the visual, aesthetic quality of nostalgia as well as the affective essence of this relation to the past. In this sense, it allows us to see these films beyond the discussions of “fetishization” or “sentimentalization” of the GDR history, as far as nostalgia does not operate within the matrix of historical “truth” but is rather directed by the category of “authenticity.” In this way, the analyzed film OLD AGENT MEN, with the help of various narrative and aesthetic means, produces an experience of distance, both temporal and spatial, between the past and the present that conveys ostalgic historical experience. Furthermore, this awareness of the unattainability of the past allows for a critical reflection that indicates a potential to act differently in the present and this way to alter our future. The conceptualization of nostalgic historical experience combined with the phenomenological approach to cinema, hence, allows us to understand ostalgie film in terms of “prosthetic memory,” which can evoke empathy to the “other”.61 For Landsberg, the difference, or distance, which is likewise cherished by nostalgic historical experience, is an essential quality for producing empathy: “In its most progressive versions, prosthetic memory creates a feeling for, while feeling different from, the other, thereby permitting ethical thinking”.62 OLD AGENT MEN, therefore, allows for reflective and critical ostalgic historical experience, providing potential for ostalgie for people who have never lived in the former GDR.

- 1The term ostalgie is a blend formed from the German words Ost[deutschland] (East Germany) and Nostalgie (nostalgia). The word rapidly came into common use in public debates in 1992 referring to nostalgic feelings towards various aspects of life in the former German Democratic Republic.

- 2Mary-Elizabeth O’Brien, Post-Wall German Cinema and National History: Utopianism and Dissent (Rochester, New York: Camden House, 2012), 83.

- 3Silke Arnold-de Simine and Susannah Radstone, “The GDR and the Memory Debate,” in Remembering and Rethinking the GDR: Multiple Perspectives and Plural Authenticities, ed. Ann Saunders and Debbie Pinfold (New York: Palgrave, 2013), 27.

- 4My translation. Original: “Während die DDR heute offiziell als Unrechtsstaat verurteilt wird, lebt sie in der Erinnerung der Menschen als wichtige Phase ihrer eigenen Biografie und Identität fort. Die abrupte und pauschale Entwertung eines halben oder ganzen gelebten Lebens führt zum Erinnerungswiderstand, den wir ‚Ostalgie’ nennen”. In: „Was bedeutet eigentlich Erinnerung? – Aleida Assmann im Gespräch. Interview bei Roland Detsch,“ Goethe Institut, January 2011. https://www.goethe.de/ins/lv/de/kul/sup/eri/ate/20809570.html

- 5Original: “kommunikative Praxis, in der mit den Erinnerungen umgegangen wird, in die Vergangenheit bearbeitet – nicht verdrängt, verleugnet oder beschwiegen – wird.” In: Thomas Ahbe, “'Ostalgie' als Laienpraxis. Einordnung, Bedingung, Funktion,” Berliner Debatte Initial. Zeitschrift für sozialwissenschaftlichen Diskurs no. 10 (1999): 93.

- 6See: Nick Hodgin, “Screening the Stasi: The Politics of Representation in Postunification Film,” in The GDR Remembered: Representations of the East German State since 1989, ed. Nick Hodgin and Caroline Pearce (Rochester, New York: Camden House, 2013), 69–91.

- 7Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991), 19.

- 8Jamie Fisher, “German Historical Film as Production Trend: European Heritage Cinema and Melodrama in The Lives of Others,” in The Collapse of the Conventional: German Film and Its Politics at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century, ed. Jaimey Fisher and Brad Prager (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010), 195.

- 9Nick Hodgin, Screening the East: Heimat, Memory and Nostalgia in German Film since 1989 (New York: Berghahn Books, 2011), 154.

- 10See Paul Betts, “The Twilight of the Idols: East German Memory and Material Culture,” The Journal of Modern History 72, no. 3 (September 2000): 731–765; Martin Blum, “Remaking the East German Past: Ostalgie, Identity, and Material Culture,” The Journal of Popular Culture 34, no. 3 (2000): 229–253; Anke Pinkert, Film and Memory in East Germany (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008).

- 11Tino Balio, “Hollywood Production Trends in the Era of Globalisation, 1990–99,” in Genre and Contemporary Hollywood, ed. Steve Neale (London: Bloomsbury, 2002), 165–184.

- 12Stephen Brockmann, A Critical History of German Film (Rochester and New York: Camden House, 2010), 469–478, Oana Godeanu-Kenworthy, “Deconstructing Ostalgia: The National Past between Commodity and Simulacrum in Wolfgang Becker’s Good Bye Lenin! (2003),” Journal of European Studies 41, no. 2 (May 2011): 161–177; Pinkert, Film and Memory in East Germany, 207; Anna Saunders, and Debbie Pinfold, Remembering and Rethinking the GDR: Multiple Perspectives and Plural Authenticities (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 92–102.

- 13Frank Ankersmit, Meaning, Truth, and Reference in Historical Representation (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012), 186.

- 14Frank Ankersmit, History and Tropology: The Rise and Fall of Metaphor (London: California University Press, 1994), 87.

- 15Ankersmit’s theory of historical experience has been gradually evolving beginning from his first work Narrative Logic (1994) to his latest book on this issue, Historical Representation (2012). Initially, Ankersmit proceeds from the concept of “historical sensation” that Huizinga understands as a fully affective relation to the past; Ankersmit introduces the term “historical experience” as synonymous but approaches it differently. For a more elaborated discussion on this see: Peter Icke, Frank Ankersmit’s Lost Historical Cause: A Journey from Language to Experience (London: Routledge, 2011), 120–123.

- 16Frank Ankersmit, Historical Representation (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001), 178.

- 17Ankersmit, Meaning, Truth, and Reference, 186. This notion, according to Ankersmit, addresses both spatial and temporal remoteness. Frank Ankersmit, “The Transfiguration of Distance into Function,” History and Theory 50, no. 4 (December 2011): 136.

- 18Ankersmit, Historical Representation, 192.

- 19Frank Ankersmit, Sublime Historical Experience (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005), 265.

- 20Ankersmit, History and Tropology, 199.

- 21Ibid., 201.

- 22Although there is an obvious overlapping between the theories of Boym and Ankersmit, they do not mention each other in their writings. Only in his later work does Ankersmit critically address Boym’s classification and acknowledges the similarity of reflective nostalgia and the kind of approach he developed earlier (Ankersmit, Meaning, Truth, and Reference, 183–187).

- 23Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2001), 44.

- 24Boym, The Future of Nostalgia, 50.

- 25Ibid., 44.

- 26Ankersmit, Meaning, Truth, and Reference, 184–185.

- 27Ankersmit, History and Tropology, 210.

- 28This essay aims to supplement the few studies that apply Ankersmit’s theory to film analysis as well as those that explicitly approach ostalgie cinema from the phenomenological perspective: Rasmus Greiner, Histospheres: Zur Theorie und Praxis des Geschichtsfilms. Berlin: Bertz+Fischer, 2020; Eleftheria Thanouli, History and Film: A Tale of Two Disciplines. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019; Sharon Macdonald, “Feeling the Past: Embodiment, Place and Nostalgia,” in Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today. New York: Routledge, 2013; Natalia Samutina, Ideologija nostalgii: problema proshlogo v sovremennom evropejskom kino [Ideology of Nostalgia: Problem of the Past in Contemporary European Cinema], Moscow: HSE Preprints, WP6 01, 2007.

- 29From the most famous examples like GOOD BYE, LENIN! and SONNENALLEE (Leander Haußmann, 1999) to less well-known DER ZIMMERSPRINGBRUNNEN / THE LIVING ROOM FOUNTAIN (Peter Timm, 2001), BERLIN IS IN GERMANY (Hannes Stöhr, 2001), KLEINRUPPIN FOREVER (Carsten Fiebeler, 2004), LIEBE MAUER / BELOVED BERLIN WALL (Peter Timm, 2009), or VORWÄRTS IMMER! / FORWARDS EVER! (Franziska Meletzky, 2017), ostalgie films take place during and right after German reunification (1989–1990).

- 30On historical experience as a constitutive core of historical films, see Rasmus Greiner, Histospheres: Zur Theorie und Praxis des Geschichtsfilms. Berlin: Bertz+Fischer, 2020.

- 31The technique of so-called ‘cold opening’ that became popular in the mid-1960s and is still characteristic of espionage films like JAMES BOND and aims to introduce the setup without or before introducing its characters.

- 32German original text: „Der Track mit dem Titel Old Agent Man beginnt wie der Kraftwerk-Klassiker Trans Europa Express und erinnert an die goldenen Zeiten des Kriminal- und Spionagefilms. Die tiefe Stimme, die 60ies-Orgeln und das dramatische Bläser-Arrangement könnten direkt für einen James-Bond-Film wie Goldfinger konzipiert sein.“ (Stephan Sommer, “Charly and the Mysterious Spy Orchestra: The/Das und Me And My Drummer machen Filmmusik,” PULS Musik (February 3, 2017). https://www.br.de/puls/musik/aktuell/charly-and-the-mysterious-spy-orchestra-kundschafter-des-friedens-soundtrack-100.html)

- 33German original text: „Das ist er also, der Zone-James-Bond… Kein Wunder, dass das Land untergegangen ist.“ [00:07:26]

- 34German original text: „Das Erfolgskonzept des „Unsichtbaren Visiers“ und ähnlicher Produktionen basiert auf der Benutzung von Strukturen des westlichen Genre-Kinos und -Fernsehens, die dabei aus Sicht der SED-Ideologen mit politisch umgekehrten Botschaften aufgeladen wurden“ (Claus Löser, “Im Visier des Unsichtbaren. Stasi im Film,” Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (October 7, 2016), 4. https://www.bpb.de/geschichte/deutsche-geschichte/stasi/229280/film).

- 35Henryk Markiewicz, “On the Definitions of Literary Parody,” in To Honour Roman Jacobson (The Hauge: Mouton, 1967), 1271. As cited in Linda Hutcheon, A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-century Art Forms (Urbana, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 52.

- 36Geoff King, Film Comedy (London, New York: Wallflower Press, 2002), 107.

- 37Wes D. Gehring, Parody as Film Genre: “never Give a Saga an Even Break” (London: Greenwood Press, 1999), 1.

- 38Hutcheon, A Theory of Parody, 54.

- 39Schatz 1981: 31.

- 40See Stefano Baschiera and Elena Caoduro, “Retro, Faux-Vintage, and Anachronism: When Cinema Looks Back at Its Analogue Past,” NECSUS: European Journal of Media Studies, 2015. https://necsus-ejms.org/retro-faux-vintage-and-anachronism-when-cinema-looks-back/; Cardwell 2002, Feyerabend 2009, Andrew Higson, “Re-presenting the National Past: Nostalgia and Pastiche in the Heritage Film,” in Fires Were Started: British Cinema and Thatcherism, ed. Lester D. Friedman (London: Wallflower, 2006), 91–109; Amy Holdsworth, Television, Memory, and Nostalgia (New York: Palgrave, 2011); Christine Sprengler, Screening Nostalgia: Populuxe Props and Technicolor Aesthetics in Contemporary American Film (New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2011).

- 41See: Kenneth Chan, “Melodrama as History and Nostalgia: Reading Hong Kong Director Yonfan’s Prince of Tears,” in Melodrama in Contemporary Film and Television, ed. Michael Stewart (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 135–152; Eleonora Ravizza, “The Politics of Melodrama: Nostalgia, Performance, and Gender Roles,” in Revolutionary Road“ Poetics of Politics: Textuality and Social Relevance in Contemporary American Literature and Culture, ed. Sebastian M. Herrmann et al. (Heidelberg: Winter, 2015), 63-80.

- 42See Ira Konigsberg, The Complete Film Dictionary (New York: Penguin Reference, 1997), 367–368.

- 43Christine Gledhill, “Rethinking Genre,” in Reinventing Film Studies, ed. Christine Gledhill and Linda Williams (London: Arnold, 2000).

- 44Boym, The Future of Nostalgia, 278.

- 45See Brockmann, A Critical History of German Film, 429.

- 46A technique also used in many nostalgia films such as MRS DALLOWAY (Marleen Gorris, 1997) or CHARIOTS OF FIRE (Hugh Hudson, 1981) where “the nostalgic perspective is built into the narrative itself since the films purport to present us the reminiscences of one of the protagonists as an older man or woman” (Andrew Higson, English Heritage, English Cinema: Costume Drama since 1980 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 83).

- 47Ankersmit, Historical Representation, 178.

- 48Jamie Baron, The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History (New York: Routledge, 2014), 110.

- 49Ankersmit, History and Tropology, 210.

- 50Baron, The Archive Effect, 110.

- 51Ibid., 129.

- 52See Alexandra Ludewig, Screening Nostalgia: 100 Years of German Heimat Film (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2011).

- 53Macdonald, “Feeling the Past,” 95.

- 54See Baschiera and Caoduro, “Retro, Faux-Vintage, and Anachronism.”

- 55See: Whitney Crothers Dilley, The Cinema of Wes Anderson: Bringing Nostalgia to Life (London and New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), Daniel Cross Turner, “The American Family (Film) in Retro: Nostalgia as Mode in Wes Anderson‘s The Royal Tenenbaums,” in Violating Time: History, Memory, and Nostalgia in Cinema, ed. Christine Lee (London: Continuum, 2008), 159–176.

- 56Higson, “Re-presenting the National Past.”

- 57Ankersmit, History and Tropology, 210.

- 58Laura Marks, Touch. Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000).

- 59Keith Jenkins, “Cohen contra Ankersmit,” in At the Limits of History: Essays on Theory and Practice (New York: Routledge, 2009), 311.

- 60Here, I refer to the article: Frank Ankersmit, “The Sublime Dissociation of the Past: Or How to Be(come) What One Is No Longer,” History and Theory 40, no. 3 (2001): 295–323.

- 61Alison Landsberg, Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).

- 62Landsberg, Prosthetic Memory, 152.

Ahbe, Thomas. “‘Ostalgie’ als Laienpraxis. Einordnung, Bedingung, Funktion.” Berliner Debatte Initial. Zeitschrift für sozialwissenschaftlichen Diskurs no. 10 (1999): 93.

Ankersmit, Frank. Meaning, Truth, and Reference in Historical Representation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012.

Ankersmit, Frank. Sublime Historical Experience. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005.

Ankersmit, Frank. Historical Representation. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001.

Ankersmit, Frank. “The Transfiguration of Distance into Function.” History and Theory 50, no. 4 (December 2011): 136–149.

Ankersmit, Frank. History and Tropology: The Rise and Fall of Metaphor. London: California University Press, 1994.

Balio, Tino. “Hollywood Production Trends in the Era of Globalisation, 1990–99.” In Genre and Contemporary Hollywood, edited by Steve Neale, 165–184. London: Bloomsbury, 2002.

Baron, Jamie. The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Baschiera, Stefano, and Elena Caoduro. “Retro, Faux-Vintage, and Anachronism: When Cinema Looks Back at Its Analogue Past.” NECSUS: European Journal of Media Studies, 2015. https://necsus-ejms.org/retro-faux-vintage-and-anachronism-when-cinema-looks-back/.

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books, 2001.

Brockmann, Stephen. A Critical History of German Film. Rochester: Camden House, 2010.

Fisher, Jamie. “German Historical Film as Production Trend: European Heritage Cinema and Melodrama in The Lives of Others.” In The Collapse of the Conventional: German Film and Its Politics at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century, edited by Jaimey Fisher and Brad Prager, 186–215. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010.

Gehring, Wes D. Parody as Film Genre: “never Give a Saga an Even Break.” London: Greenwood Press, 1999.

Gledhill, Christine. “Rethinking Genre.” In Reinventing Film Studies, edited by Christine Gledhill and

Godeanu-Kenworthy, Oana. “Deconstructing Ostalgia: The National Past between Commodity and Simulacrum in Wolfgang Becker’s Good Bye Lenin! (2003).” Journal of European Studies 41, no. 2 (May 2011): 161–177.

Higson, Andrew. “Re-presenting the National Past: Nostalgia and Pastiche in the Heritage Film.” In Fires Were Started: British Cinema and Thatcherism, edited by Lester D. Friedman, 91–109. London: Wallflower, 2006.

Higson, Andrew. English Heritage, English Cinema: Costume Drama since 1980. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Hodgin, Nick. Screening the East: Heimat, Memory and Nostalgia in German Film since 1989. New York: Berghahn Books, 2011.

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-century Art Forms. Urbana, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000.

Icke, Peter. Frank Ankersmit’s Lost Historical Cause: A Journey from Language to Experience. London: Routledge, 2011.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991.

Jenkins, Keith. “Cohen contra Ankersmit.” In At the Limits of History: Essays on Theory and Practice, 295–314. New York: Routledge, 2009.

King, Geoff. Film Comedy. London, New York: Wallflower Press, 2002.

Löser, Claus. “Im Visier des Unsichtbaren. Stasi im Film.” Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (October 7, 2016). https://www.bpb.de/geschichte/deutsche-geschichte/stasi/229280/film.

Landsberg, Alison. Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

Macdonald, Sharon. “Feeling the Past: Embodiment, Place and Nostalgia.” In Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Marks, Laura. Touch. Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000.

O’Brien, Mary-Elizabeth. Post-Wall German Cinema and National History: Utopianism and Dissent. Rochester, New York: Camden House, 2012.

Pinkert, Anke. Film and Memory in East Germany. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008.

Saunders, Anna, and Debbie Pinfold. Remembering and Rethinking the GDR: Multiple Perspectives and Plural Authenticities. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Simine, Silke Arnold-de Simine, and Susannah Radstone. “The GDR and the Memory Debate.” In Remembering and Rethinking the GDR: Multiple Perspectives and Plural Authenticities, edited by Ann Saunders and Debbie Pinfold, 19–33. New York: Palgrave, 2013.

Sommer, Stephan. “Charly and the Mysterious Spy Orchestra: The/Das und Me And My Drummer machen Filmmusik.” PULS Musik (February 3, 2017). https://www.br.de/puls/musik/aktuell/charly-and-the-mysterious-spy-orch…;

„Was bedeutet eigentlich Erinnerung? – Aleida Assmann im Gespräch. Interview bei Roland Detsch.“ Goethe Institut Lettland (January 2011). https://www.goethe.de/ins/lv/de/kul/sup/eri/ate/20809570.html.