Brazilian Cinema at the Berlin International Film Festival

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Rocha, Carolina: Brazilian Cinema at the Berlin International Film Festival. In: Research in Film and History. New Approaches (2019), pp. 1–14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14814.

Film scholar Marijcke de Valck argues that film festivals “are sites of passage that function as the gateways to cultural legitimation” (De Valck 2007: 38). More recently, Andreas Kötzing and Caroline Moine have pointed out the political dimensions of these cultural events, particularly during the second half of the twentieth century:

Film festivals, whether they called themselves international or not, were at the epicenter of the various circulations, exchanges, and tensions that fueled the economic and cultural development of the Cold War. (Kötzing/Moine 2017: 10)

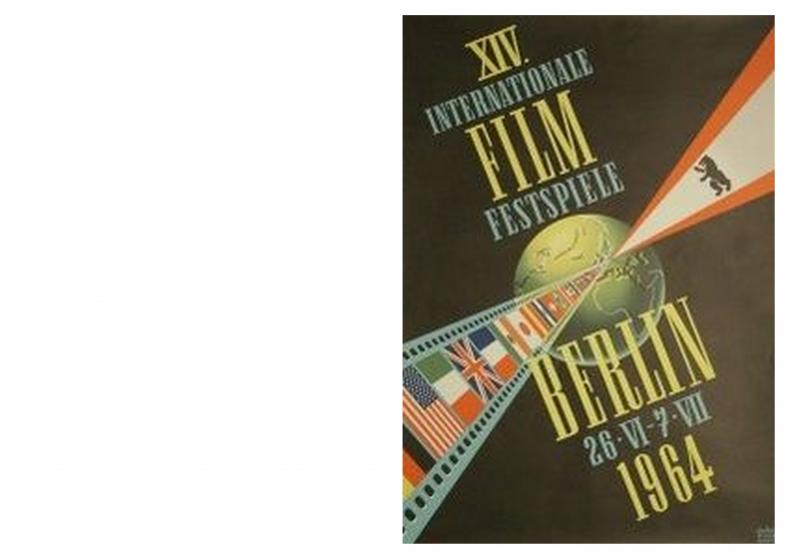

Building on these insights and utilizing multiple film reviews, this article analyzes the performance of two Brazilian films—OS CAFAJESTES (BRAZIL 1962) and OS FUZIS (BRAZIL/ARGENTINA 1964)—that were invited to be screened at the Berlin International Film Festival in the early 1960s and were both nominated for the Golden Bear. I argue that the Berlin International Film Festival benefited from an interest in Brazilian cinema at a time when the politics of the Cold War challenged cinema’s role as a bridge between East and West. As I will show below, during the Berlin International Film Festival’s first decade, only films from Western Europe and the United States received Golden Bears. In the early 1960s, however, the juries of the festival started recognizing other cinemas from around the world. Brazilian films were the first to achieve a sustained interest during that decade. In addition, the nominations garnered by Ruy Guerra’s films at the Berlin International Film Festival constituted a crucial recognition for the emergent 'Cinema Novo', a new revolutionary type of filmmaking. In this instance, it is possible to see the processes of inclusion and exclusion that national cinemas will undergo in order to be part of a national canon. Liz Czach explains: "Selection decisions made regarding the canon sometimes correspond strongly with the kind of evaluative judgments made in programming" (Czach 2004: 79). In other instances, the appreciation shown in film festivals may help rectify a film’s weak performance in its home country because “the festival circuit and festival screenings function to gather potential critical, public, and scholarly attention for individual films and directors” (Czach 2004: 82). I begin this article by tracing the characteristics of the Berlin International Film Festival within the circuit of European film festivals and the politics of the early 1960s that created the conditions for an interest in Brazilian cinema.

The Berlin International Film Festival

Initially, European film festivals were conceived as showcases for the arts, but they also had political roles that transcended the realm of culture. The Biennale of Venice, which first took place in 1932, consisted of an exhibition of international films, but later became a forum that was coopted by Fascist and Nazi ideologues. The first Cannes Film Festival took place briefly—for only 48 hours—in September 1939, but was then interrupted by the initial hostilities of World War II. Relaunched in 1946, it constituted an opportunity to inject vitality into southern France. Despite the financial difficulties of the first post-war years, the Cannes Film Festival quickly became a major cultural event that attracted worldwide attention. For its part, the Berlin International Film Festival (also called the Berlinale) benefited from the staunch support of American officer Oscar Martay who was instrumental in its creation. It began in 1951 as a means to rebuild a destroyed city and reestablish its cultural prominence (Jacobsen 2001: 11). Moreover, the Berlin International Film Festival was entrusted with the task of easing political tensions in a divided city in which the animosity of the Cold War was ubiquitous. Scholar Heide Fehrenbach explains that from the outset, the goal of “the festival was to foster the image of a revitalized, democratic Berlin and serve as a tribute to Western cultural vitality” (Fehrenbach 1995: 238). Thus, in addition to boosting Berlin as a cultural metropolis, the festival aimed to represent the values of freedom and democracy in the context of post-1945 Europe. Its launch in the early 1950s was greatly bolstered by the participation of Western European countries—England, Ireland, Switzerland, and Spain—and others, such as Australia and the United States (Jacobsen 2001: 19).

The first decade of the Berlin International Film Festival was full of challenges. First, funding and support for the festival came from the occupying nations of West Berlin—the United States, Britain, and France (Jacobsen 2001: 65). Second, the festival faced a lengthy process of recognition. The International Federation of Film Producers Associations (FIAPF), an association of 30 leading film-producing countries that managed film festivals, granted Berlin a B status in 1952 (Fehrenbach 1995: 245). A year later, the festival became a permanent event—until then the Berlin senate had to pass annual approvals for its continuity—, and in 1955, it was officially recognized as an A film festival, joining Venice and Cannes. The promotion of Berlin to a world-class film festival encouraged new investments in infrastructure: the 1957 festival was held in a state-of-the art venue, the Zoo Palast, composed of two movie theatres. Third, several features of the Berlin International Film Festival underwent changes during the first decade. Prizes were first awarded by a German jury in 1951, then by the audience from 1952-1955, and finally from 1956 onwards again by an international jury of seven or nine members. Despite the varied ways (attendees’ vote, jury) used to determine the film festival’s awards, by 1962, only films from Western European countries and the United States had garnered awards (see Table 1). Only in 1963, twelve years after the festival’s first edition, did a film outside of these countries receive a Golden Bear, the festival’s highest award: Japan took home the prize for BUSHIDO (JAPAN 1963). This development was a consequence of changing conditions both in Berlin and in world cinemas.

| Year | Film | Country |

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | FOUR IN A JEEP | Switzerland |

| 1952 | ONE SUMMER OF HAPPINESS | Sweden |

| 1953 | THE WAGES OF FEAR | France |

| 1954 | MIRACLE OF MARCELLINO | Spain |

| 1955 | DIE RATTEN (THE RATS) | Germany (GDR) |

| 1956 | INVITATION TO DANCE | USA |

| 1957 | TWELVE ANGRY MEN | USA |

| 1958 | WILD STRAWBERRIES | Sweden |

| 1959 | THE COUSINS | France |

| 1960 | EL LAZARILLO DE TORMES | Spain |

| 1961 | THE NIGHT | Italy |

| 1962 | A KIND OF LOVING | UK |

| 1963 | BUSHIDO | Japan |

| 1964 | DRY SUMMER | Turkey |

Source: www.berlinale.de

In the early 1960s, political events in Berlin and around the world dramatically changed the global landscape. The sudden building of the Berlin Wall further separated the city’s residents and deepened the mistrust and antagonism between the capitalist West and the socialist East. If, during the 1950s, American officials sought to use film in a “cultural offensive designed to reach the populations to the East and counter the influence of officially sponsored popular events there” (Fehrenbach 1995: 239), the creation of the Berlin Wall considerably diminished the exchanges with the Soviet-controlled part of Berlin, as the cheap border cinemas were no longer accessible to the people of East Berlin. A consequence of this rift was an increased awareness in domestic and foreign policy on the part of West Berliners. This politicization fostered an interest in Third World countries that provided an opening at the Berlin International Film Festival for Latin American films in general and Brazilian films in particular. The Cuban Revolution, the war in Vietnam, and the decolonization process in Africa, were all political occurrences that nuanced the East-West concern of West Berliners and also impacted the function of the film festival. Moreover, the arrival of numerous students from Africa, Asia, and Latin America contributed to a better understanding of Third World politics among students and New Left sympathizers (Slobodian 2012: 4). A case in point are the ideas of Iranian intellectual and West Berlin resident, Bahman Nirumand, who held that, “the category of the Third World did not denote comparative backwardness or inferiority. To be third was not to be last or behind but to be something new, and something more” (Slobodian 2012: 5). This engagement of West Berliners with the Third World, which took place as a result of the tensions between West and East—First and Second World, respectively—, transcended the political field and impacted the cultural realm. Scholar Cristina Gerhardt judiciously asserts that “the 1960s witnessed profound transformations in politics, in cinema and in their intersection. This certainly holds true in West Berlin” (Gerhardt 2017: 1). These changes were also felt by the organizers of the Berlin International Film Festival.

While Latin American directors, actors, and producers had participated as members of the international jury of the Berlin International Film Festival since 1956, the fact that in the early 1960s there was a general atmosphere more receptive to new political ideas and the plight of Third World countries in West Berlin may have contributed to the positive reception of Brazilian films. The relationship between the Berlin International Film Festival and the early 'Cinema Novo' films shows the ways in which both entities found such ties as mutually enriching, contradicting Owen Evans, who proposes a post-colonial approach to investigate the role of film festivals: “As soon as we begin to view the world of cinema as an unequal struggle it becomes clearer how the post-colonial model can help us analyse the role of film festivals” (Evans 2007: 26). A key player in the promotion of Brazilian films at the Berlin International Film Festival was the co-founder of the Forum, Peter Schumann, who ran special exhibitions of Latin American films from the 1970s until his retirement in 2006. The director whose Brazilian films were first recognized at the Berlin International Film Festival was Ruy Guerra (1931–), who was born in Mozambique and after studying cinema in Paris, migrated to Brazil in the late 1950s.

The Early 1960s: Brazilian Films Come to Berlin

In the early 1960s, Brazil adopted a more open brand of foreign policy. While traditionally it had relied on a diplomacy closely aligned to that of the United States, the presidency of Jânio Quadros (1961) inaugurated a more “globalist” foreign policy “valorizando as relações com pequenhas e médias potências no eixo Norte-Sul na busca de maior autonomia no cénario internacional” [prioritizing foreign relations with small and medium-sized powers in the North-South axis in search of a greater autonomy on the international stage] (Lobhaur 2000: 18). This shift in the Brazilian foreign policy was also noticeable during the presidency of João Goulart (1961–1964), who aimed to expand Brazil’s foreign markets, following policies that did not necessarily mean supporting Western capitalism, and strengthening North-South relations. Among the countries that saw a more solid relationships with Brazil was the Federal German Republic (Lobhaur 2000: 20). Soft power, a term coined by Joseph Nye in the 1990s that refers to the “power of attraction” rather than coercion (Cooke 2016: 5), was also deployed to strengthen relationships between both countries.

OS CAFAJESTES by Ruy Guerra was the first Brazilian film to be nominated for a major award at the Berlin International Film Festival. Shot in black and white, the film centers around two immature men, Jandir (Jece Valadão) and Vavá (Daniel Filho), who spend their days tricking young women. Jandir pretends to seduce Leda (Norma Bengell) and takes her to a pristine beach, where he encourages her to undress and bathe in the sea, but his suggestion is a ruse so that Vavá, who is hidden in the car’s trunk can photograph her and sell the pictures to his uncle who is Leda’s lover. A long, traveling shot captures the young woman’s humiliation and betrayal by a smooth-talking Jandir, but Leda turns the tables and offers the youth a chance to trick Vilma (Lucy de Carvalho), who is her lover’s daughter, as well as Jandir’s cousin and the object of his affections. When Vavá attempts to rape Vilma, Jandir who is in charge of photographing the incident to extort money from the girl’s rich father, intervenes in favor of the girl. She later has consensual sex with Vavá, despite the fact that Jandir confesses his love for her. OS CAFAJESTES presents the young men as drifters or anti-heroes, similar to Jean-Luc Godard’s Michel in À BOUT DE SOUFFLE (FRANCE 1960). In the film’s final five minutes, local and international news refers to a context of intense politicization, particularly in Africa and Latin America, revealing the youth’s lack of engagement with contemporary politics.

The plot of OS CAFAJESTES revolves around the topics of mass culture, alienation, and consumerism. Vavá and Jandir aspire to consumption without participating in production, while Leda and Vilma are objects of male sexual desire, pawns in their games, that can be easily substituted. Scholar Albert Elduque highlights the message on consumption in Guerra’s opera prima:

O círculo de inutilidade das trocas capitalistas é também um círculo sobre a inutilidade do consumo, ou, mais exatamente, sobre seu excesso e seu limite

[the circle of futility of capitalist barters is also a circle about the futility of consumption, or more exactly, about its excesses and limits] (Elduque 2015: 487).

Indeed, the superficial events that constitute the plot sharply contrast with the report of local and international news in the film’s final minutes, stressing the senseless pursue of pleasure in the young protagonists as well as their unproductive roles in society.

The reception of OS CAFAJESTES was uneven among the public and critics. Spectators tended to support the film. As Alexandre Figuerôa Ferreira explains, Guerra’s film “foi o primeiro sucesso comercial de uma produção com pequeno orçamento e fora do sistema tradicional de produção das chanchadas e das companhias” [was the first commercial success of a production with a modest budget and without following the traditional system of the production of chanchadas and studios] (Figuerôa Ferreira 2000: 21). Brazilian filmmakers Nelson Pereira dos Santos, Carlos Diegues, Glauber Rocha, Paulo César Saraceni, and Walter Hugo Khouri, who were looking for a new cinematic language recommended OS CAFAJESTES as one of the first films of 'Cinema Novo' (Azevedo 1962: n.p.). Nonetheless, documentary filmmaker Maurice Capovilla, active in the 1960s, held that OS CAFAJESTES was a film that lacked a commitment to Brazilian politics: “Na época, não queríamos um cinema vazio, com polêmicas vazias” [At that time, we did not want an empty cinema, with empty themes] (Cadernuto 2013: 18). Capovilla is probably alluding to the fact that the long nude and rape scene—both widely discussed—were included to épater the Brazilian bourgeoisie. For his part, Brazilian film director Cacá Diegues explains that in the film, Guerra was the first to use jump cuts and other innovative techniques (Diegues 2014: 134). OS CAFAJESTES also divided the film critics of the most important Brazilian dailies. While the film critic of Correio da Manhã mentioned the influences of the 'Nouvelle Vague' and predicted the film’s difficulty in attracting foreign acclaim, particularly at Cannes (Moniz Vianna 1962: n.p.),1 Ely Azevedo from Tribuna da Imprensa, cited the interest of the UFA (Universum Film-Aktien Gesellchaft), a German film company, and that of Alfred Bauer, director of the Berlin International Film Festival, as one of the film’s supporters. What is important to note is that Bauer’s support came two months before the 11th Berlin International Film Festival took place. This backing was fundamental for two reasons: first, it came at a time when censorship in Brazil was beginning to make its way into Brazilian cinema, and second, 'Cinema Novo', which was seeking foreign cultural legitimation as a way to attract more Brazilian supporters, was able to capture Bauer’s interest and that of some jurors at the festival.

The advent of 'Cinema Novo' in Brazil marked a break with old ways of making and distributing film in Brazil. Young, urban, middle-class filmmakers despised the light comedies and sexually-explicit films, called 'chanchadas', that were popular in the 1950s, and thus, hoped to make films that portrayed Brazilian reality and the country’s structural problems amid a climate that favored modernization. For Ismael Xavier, 'Cinema Novo' entailed a “project of a nationalist, leftist, and commercial audiovisual culture in Brazil” (Xavier 1997: 22). As 'chanchadas' were linked to a studio system that duplicated Hollywood productions, 'Cinema Novo' embraced independent filmmaking with a focus on the socio-economic problems affecting Brazil. Some of these films relied on loans made by banks, while others were financed by a tax levied on performances and were regulated by a law to help cinema. Even when authorities decried the politics of 'cinenovistas', they did not withhold the funds for their films (Figuerôa Ferreira 2000: 22). 'Cinema Novo' films scrutinized the plights of the dispossessed and Brazil’s role in the East-West Cold War rivalry. Both issues resonated with the zeitgeist in West Berlin, where important developments were taking place.

The year OS CAFAJESTES was nominated for the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival (1962) constituted a low point for the German festival. Ten months before its opening in 1962, during a single night, a wall was erected around Berlin, separating the East from the West. This event not only exacerbated the political tensions of the Cold War, but also negatively impacted the number of filmgoers who attended the Berlin International Film Festival that year and in subsequent years, as residents of East Berlin found it increasingly difficult to participate. Perhaps as a sign of dissatisfaction with contemporary politics, critics deemed the Berlin Film Festival’s 1962 selection poor and even called for the festival to give up its A status (Jacobsen 2001: 108).

The Berlinale’s official record also mentions two additional consequences of the heightened negativity towards the film festival and the film shown. First, a different selection committee was recommended: “‘it’s not only important for employees to be able to travel, the more important question is: who travels,’ wrote Manfred Delling in an article in Die Welt” (www.berlinale.de). Second and more importantly, six months before the opening of the 11th edition of the Berlin Film Festival in 1962, 28 German filmmakers signed the Oberhausen Manifesto, calling for the emergence of a new kind of filmmaking that would be less concerned with commercial performance and more interested in experimentation and innovation: “The old film is dead. We believe in the new one” (Oberhausen Manifesto). This emphasis on new forms of filmmaking paved the wave for the positive reception of films from different parts of the world.

Brazilian cinema was the first in Latin America to capitalize on these new winds of change at the Berlin Film Festival, particularly one film directed by Ruy Guerra, OS FUZIS, which was nominated for the Golden Bear in 1964. Shot entirely on location with a modest budget, and a loan extended by a Brazilian state bank, OS FUZIS is set in a poor village besieged by a prolonged drought, where a religious leader convinces his followers to revere a sacred ox under an unforgiving sun. A driver, Gaúcho (Átila Iório), arrives at the village at almost the same time as an army unit also enters to offer protection to the local mayor who fears that the hungry people will steal his warehouse. In the tense wait, a member of the army platoon makes fun of the local residents as the sergeant sides with the corrupt mayor who expects to make a handsome profit despite the drought. Gaúcho first challenges the soldier shaming the local patrons and later decries the death of a shepherd shot by accident by the same reckless soldier, especially after the platoon hides this death, showing their cowardice and lack of morals. Finally, when Gaúcho sees a young father emotionlessly accepting that his child has passed away because of hunger, the driver engages in a shootout with the soldiers who are driving away with sacks of grain that could have fed the town’s people. Hunted by the militia men, Gaúcho is shot repeatedly, in another instance of abuse on the part of the platoon. Gaúcho’s death precedes the violent killing of the sacred ox by the hungry mob, revealing a parallel that presents the soldiers just as desperate as the starved townsfolk.

In OS FUZIS, Guerra depicts the themes of hunger and poverty, central to the tenets of 'Cinema Novo', but which could be problematic for an international reception. While Guerra’s film precedes the launching of Glauber Rocha’s much-cited 1965 text, Estética da fome [Aesthetic of Hunger], OS FUZIS critiques Brazilian material conditions, a key feature of the first phase of the 'Cinema Novo' movement, characterized by “la terre sèche filmée de façon primitive et ayant comme protagoniste l’homme vivant dans des conditions précaires avec sa propre culture” [the dry, primitive land and having as the main character the man who lives in precarious conditions with his own culture] (Figuerôa Ferreira 2000: 31). It should be added that the primitivism that is a key thematic element in OS FUZIS also informs its mode of production as a low-budget independent film. Regarding the topic of hunger, Rocha thought it was not easily comprehended by Europeans:

Nós compreendemos esta fome que o europeu e o brasileiro na maioria não entende. Para o europeu é um estranho surrealismo tropical

[We understand this hunger that the Europeans and the majority of Brazilians do not. For the European it is an alien tropical surrealism] (Rocha 1965: n.p.)

Despite Rocha’s view that Europeans would fail to understand, the success of OS FUZIS at the Berlin International Film Festival and his own film DEUS E O DIABO NA TERRA DO SOL (BRAZIL 1964), at Cannes proved that although these films depict Brazilian life in the countryside, they are accessible to international audiences.

While the plot of OS FUZIS contains universal elements—religious fanaticism, exploitation of the poor, impunity of those in power—, the film’s denunciatory tone displays elements that made it attractive to the international jury of the Berlin International Film Festival, which awarded it the Silver Bear (Jury Prize) to Guerra’s second film. OS FUZIS could be seen as a modern version of Plato’s cave allegory in which the outsider, Gaúcho, tries to enlighten the masses when he fights against the mayor’s greed and the passivity of those who are experiencing the famine. Guerra initially set the plot in Greece and attempted to shoot there in the late 1950s, but he was not able to obtain the permits needed. Consequently, he reworked the storyline and added the subplot of the drought, which was based on a real natural disaster that took place in Brazil in the 1920s, as a way to insert experiences from the Brazilian countryside. Despite the fact that Brazil was not the original setting of OS FUZIS, the film was seen in Berlin as in alignment with the direction of the New German Cinema proposed in the Oberhausen Manifesto. OS FUZIS is critical of group mentality and the abuse of power displayed by the army platoon. The hero, Gaúcho, stands alone on a middle-ground—curiously, as a driver of goods—through which he is able to prove that his knowledge is wider than that of one of the soldiers, and he can empathize with the plight of the hungry masses. As he rebels against injustices, he stands out for the committed intellectuals and personifies the directors of the Brazilian 'Cinema Novo' who decried the exploitative nature of capitalism. The cinenovistas’ rejection of capitalism and the surplus generated for the benefit of the upper classes resonated with ideologies that circulated in Germany. Sabine Hake explains:

the specter of American mass culture in Berlin in the early 1950s brought together a number of ideological concerns: the advance of global capitalism and its steady companions, militarism and imperialism; the leveling effects of modern mass culture on bourgeois high culture and traditional working-class culture. (Hake 2005: 155)

Guerra’s film was interpreted as an instance of the camera as a gun, that is to say, a means of portraying the deep inequalities that would lead to the emancipation of oppressed masses, and ultimately, to national liberation from the exploitative capitalism (Xavier 2006: 67).2 The fact that a military 'coup d’état' took place in Brazil in April 1964, two months before the opening of the 14th Berlin International Film Festival, and that the film had to be submitted to a Brazilian security commission for approval to participate in the festival, may have played into the film’s favorable international reception as a document of the deplorable conditions that called for the mobilization of the Third World masses.3

OS FUZIS arrived in Berlin at a special time in the festival’s trajectory, one that encouraged renewal and interest in non-Hollywood cinemas, particularly those that dealt with social themes. Because of the Oberhausen Manifesto of 1962 and the political effervescence of the early 1960s, there was a new opportunity for non-Hollywood and non-European cinemas. Regarding the first ones, Thomas Elsaesser mentions the way in which New German Cinema in the early 1960s was either indifferent to or despised Hollywood films (Elsaesser 2005: 170). As Hollywood began to lose its hegemonic grip among West German moviegoers, the innovative film productions of Britain, France, Poland, and Brazil gained ascendancy (Elsaesser 2005: 174). The rejection of Hollywood productions was part of a larger mood affecting some West Germans: the New Left strongly opposed imperialism, and in so doing, “reoriented their politics eastward and southward” (Slobodian 2012: 4). The West Germans’ attention to other regions was also due to their common ideologies, which were highly influential for their independent cinemas.

In the early 1960s, leftist political ideas around the world noticeably impacted film productions that were well received at the Berlin Film Festival. As mentioned earlier, in 1963, BUSHIDO (Imai Tadashi), a Japanese film, became the first non-Western film to win the Golden Bear, the festival’s main award. Imai Tadashi was part of the Japanese New Wave, which according to David Desser, was comprised of films “which take a political stance in a general way or toward a specific issue, utilizing a deliberately disjunctive form compared to previous filmic norms in Japan” (Desser 1988: 4). In 1964, the main award of the Berlinale went to the Turkish film SUSUZ YAZ/DRY SUMMER (Metin Erksan) (TURKEY 1964), and OS FUZIS was the first Brazilian film to be recognized at the Berlin International Film Festival with a Golden Bear nomination. The common link among the three films from countries as diverse as Japan, Turkey, and Brazil was independent filmmaking with a political slant. Scholar Murat Akser characterizes independent Turkish filmmakers of the 1960s, among whom Metin Erksan was included:

Many of these filmmakers were well educated and shared an urban background. Their works focused on the alienation of modern life, class differences, gender issues, and ethnic conflict. (2015: 135)

These themes also appear, albeit to different degrees, in Guerra’s films OS CAFAJESTES and OS FUZIS. Guerra was a figure at the forefront of new formalist and ideological debates about filmmaking. According to fellow Brazilian filmmaker Cacá Diegues,

Valia a pena ouvir Ruy [Guerra] falar sobre o que havia aprendido no IDHEC [Institut des Hautes Études Cinématographiques]. Para mim, eram novos aqueles conhecimentos da fabricação de um filme, os comentários sobre os filmes que via, sempre teorizados aguerridamente como argumentos cinematográficos e ideológicos.

[It was worth listening to Ruy [Guerra] talk about what he had learned at IDHEC. To me, those were new ideas about the making of a film, his comments about the films he watched, always passionately theorized as cinematic and ideological insights.] (Diegues 2014: 135)

Those new ideas concerned the role of film as a pedagogical tool for the masses and directors as proponents of radical changes in their societies.4

By appreciating avant garde films from cinemas outside Western Europe and the US, the Berlin Film Festival was able to appease domestic critics and maintain its role as a first-class film festival in the 1960s. The criticism, that in 1961, “The ‘Berlinale’ had difficulty in recognizing the signs of the times” (Jacobsen 2000: 99) was taken seriously by festival organizers who considered creating a new category that would reward films from countries other than Western Europe and the US (Jacobsen 2000: 115). This interest in expanding the origin of the awarded films implied a re-definition of the Berlin International Film Festival. As Julian Springer mentions,

The ambition of many festivals is … to aspire to the status of a global event, both through the implementation of their programming strategies and though the establishment of an international reach and reputation. (Springer 2001: 139)

Thus, in seeking to make room for films from Asia and Latin America, the Berlin International Film Festival sought to preserve its role as a significant cultural event by reinventing itself, particularly in relation to the film production of other parts of the world, a move that would seal its global reputation and show its adaptation to a more diverse group of film producers. In this sense, the Berlin juries’ appreciation of films from Brazil, Japan, and Turkey worked as a form of domestic cultural legitimation: at a time when young German filmmakers were working intensely to create the New German Cinema and to shake off American tutelage and cinematic models, the inclusion of films from Third World and non-Western countries and their positive reception at the Berlin International Film Festival served to open new possibilities and enlarge mutual exchanges, particularly between German and Brazilian cinema.

There were several consequences of these interactions. First, the Berlin International Film Festival was able in the early 1960s to transform itself from “a tribute to Western capitalism, commercialism, and the popular allure of mass culture” (Fehrenbach 1995: 253) to a festival which accepted and rewarded new forms of filmmaking, particularly those with a focus on social issues, such as OS FUZIS. Gerhardt mentions 'Cinema Novo' as one of the global cinemas that was positively received and that has been considerably researched (Gerhardt 2017: 2). The worldwide reception of these movements owes much to their success at the Berlin International Film Festival. As Elsaesser notes,

the 1960s, for instance, were the time of the growing importance of the film festival circuits, which emerged as the new force in European cinema, developing an alternative system of promotion, distribution and exhibition (and sometimes even an alternative system of production), coexisting with Hollywood. (Elsaesser 2005: 175)

Berlin and Cannes were crucial European film festivals for the launch of 'Cinema Novo' in Europe.5 This support was, as Leonor Souza Pinto points out, a protective shield against censorship:

Paralelamente à repressão cultural no país, uma inteligente política de difusão da imagem “democrática” do país no exterior é montada. Para isso, lançam mão da excelente produção cinematográfica brasileira. O mesmo cinema que, internamente, combatem ferozmente.

[Parallel to the cultural repression in the country, an intelligent policy of dissemination of the country’s democratic image is deployed. For this, they make use of the excellent Brazilian cinematic production. The same cinema that, internally, was harshly silenced.] (Souza Pinto n.d.: 4)

Second, as a hub of dissemination of new cinematic forms in the early 1960s, the Berlin International Film Festival, by showcasing the work of emerging filmmakers, provided an international platform for Guerra’s films in particular and 'Cinema Novo'’s productions in general, which also translated to the ability of reaching international audiences and fellow directors in Europe. Two examples suffice here. First, cultural journalist Peter Schumann curated a special exhibition of Brazilian films for the Berlin International Film Festival in 1966. These films, among which was OS FUZIS, were later shown on German television. Two years later, Schumann directed four documentaries for German television about 'Cinema Novo'. Second, the originality of 'Cinema Novo' influenced filmmakers beyond Brazil. Elduque has recently alluded to “a dinâmica resistência/mudança, que irmana Herzog e Guerra, articula-se com as lógicas do consumo” [the dynamic resistance/change that unites Herzog and Guerra is related to the logic of consumerism] (Elduque 2015: 485). In the case of Ruy Guerra, he would continue to be an important referent of Brazilian culture in Germany in the 1970s. While there is still much more to explore about the collaborations between Herzog and Guerra, the latter took part as an actor in Herzog’s AGUIRRE, THE WRATH OF GOD (WEST GERMANY 1972), and as Nagib notes, there are notable traces of 'Cinema Novo' in Herzog’s films (Nagib 2007: 34). These collaborations contradict Owen’s view that European film festivals establish post-colonial relations between Old and New World cinemas.

To conclude, the positive reception of two 'Cinema Novo' films at the Berlinale in the early 1960s yielded many benefits for Brazilian cinema and the Berlin Film Festival. By screening and celebrating independent Brazilian films that incorporated new techniques and portrayed the disparities in different ways of life in Brazil, the organizers and juries of the Berlin International Film Festival revealed their attention to the demands of directors of the New German Cinema and spectators who were politically active, rejecting the traditional links between West Berlin and Hollywood cinema. For Brazilian cinema, the nominations did much to legitimize the views of young directors involved in 'Cinema Novo' who, despite the 1964 dictatorship in Brazil, were able to continue filming and expressing anti-capitalist views that were shared by leftist intellectuals and filmmakers all over the world.

- 1Alexandre Figueirôa Ferreira confirms that indeed that was the case: OS CAFAJESTES [LA PLAGE DU DÉSIR, French Translation] “passa presque inaperçu, malgré une publicité à base de nus” [was almost ignored despite a promotional campaign with images of naked women] (Figueirôa Ferreira 2000: 42).

- 2Lúcia Nagib talks about “moments of radicalism in Brazilian cinema in films by Nelson Perreira dos Santos, Ruy Guerra, and Glauber Rocha” (Nagib 2007: 36).

- 3Nagib points out that DEUS E O DIABO NA TERRA DO SOL, “filmed in 1963, at a time when there was great political hope in Brazil, draws a progressive hero who finally frees himself from the country retrograde and anti-republican influences” (Nagib 2007: 13).

- 4Diegues succinctly describes the goals of 'Cinema Novo': “No delírio de fazer filmes decisivos, num país onde o cinema não existia, o projeto do Cinema Novo, a nossa geração de cineastas, era muito simples, um programa de apenas três pontos: mudar a história do cinema, mudar a realidade brasileira, mudar o mundo” [In the rush to make important films, in a country where cinema didn’t exist, the project of cinema novo, our generation of filmmakers was very simple, a program of only three points: change the history of cinema, change the Brazilian reality, change the world] (Diegues 2014: 82).

- 5For more on this, please see Figueirôa Ferreira’s La vague, p. 42.

Akser, Murat. “Turkish Independent Cinema: Between Bourgeois Auterism and Political Radicalism.” In Independent Filmmaking Around the Globe, edited by Mary Erickson and Doris Baltruchat, 131–148. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015.

Azevedo, Ely. “A subverção de ‘Os cafajestes.’” A Tribuna da Impresa April 3, 1962. http://www.memoriacinebr.com.br/PDF/0230148I013.pdf (accessed October 10, 2018).

Cadernuto, Reinaldo. “Os anos 1960 em revisão: um depoimento de Maurice Capovilla.” Revista brasileira de estudos de cinema e audiovisual 2.2 (2013): 1-20. https://rebeca.emnuvens.com.br/1/article/view/311/116 (accessed July 30, 2018).

Cooker, Paul. “Soft Power, Film Culture and the BRICS.” New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film 14.1 (2016): 3–15.

Czach, Liz. “Film Festivals, Programming, and the Building of a National Cinema.” The Moving Image 4.1 (2004): 76–88.

Desser, David. Eros plus a Massacre: An Introduction to the Japanese New Wave Cinema. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1988.

De Valck, Marijke. Film Festivals: From European Geopolitics to a Global Cinephilia. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007.

Diegues, Cacá. Vida de Cinema: Antes, durante e depois do Cinema Novo. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Objetiva, 2014.

Elduque, Albert. “Werner Herzog e Ruy Guerra: formas da estética da fome.” Atas do IV Encontro Anual Associação de Investigadores de Imagem em Movimento (2015): 480–490. http://www.aim.org.pt/atas/pdfs/Atas-IVEncontroAnualAIM-41.pdf (accessed November 4, 2018).

Elsaesser, Thomas. “German Cinema Face to Face with Hollywood: Looking Into a Two-Way Mirror.” In Americanization and anti-Americanism. The German Encounter with American Culture after 1945, edited by Alexander Stephan, 166–185. New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2005.

Evans, Owen. “Border Exchanges: The Role of the European Film Festival” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 15.1 (2007): 23–33.

Fehrenbach, Heide. Cinema in Democratizing Germany. Reconstructing National Identity after Hitler. Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Figueirôa Ferreira, Alexandre. Cinema Novo: a onda do jovem cinema e sua recepção na França. Campinas, SP: Papirus, 2004.

Figueirôa Ferreira, Alexandre. La Vague du Cinema Novo en France fut-elle une invention de la critique? Paris: L’Harmattan, 2000.

Gerhardt, Cristina. “Introduction: Cinema in West Germany in 1968” The Sixties: A Journal of History, Politics and Culture 10 (2017): 1–9.

Hake, Sabina. “Anti-americanism and the Cold War: On the DEFA.” In Americanization and anti-Americanism: The German Encounter with American Culture after 1945, edited by Alexander Stephan, 148-165. New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2005.

Jacobsen, Wolfgang. 50 Years Berlinale. Berlin: Nicolai, 2000.

Lobhauer, Christian. Brazil-Alemanha (1964–1999) Fases de uma Parceria. São Paulo: Fundação Konrad Adenauer, 2000.

Moniz Vianna, A. “Os Cafajestes” Correio da Manhã. February 14, 1962. n.p. http://www.memoriacinebr.com.br/PDF/0230148I002.pdf (accessed November 24, 2018).

Nagib, Lúcia. Brazil on the Screen: Cinema Novo, New Cinema, Utopia. New York: I.B. Tauris, 2007.

Slobodian, Quinn. Foreign Front. Third World Politics in Sixties Germany. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2012.

Souza Pinto, Leonor. “O Cinema Brasileiro face à censura imposta pelo regime militar no Brasil” Memória do cinema brasileira (no date) – 1964/1988. (accessed November 10, 2018).

Stringer, Julian. “Global Cities and the International Film Festival Circuit.” In Cinema and The City: Film and Urban Societies in Global Context, edited by Mark Shield and Tony Fitzmaurice, 134–144. Oxford: Blackwell, 2001.

Xavier, Ismael. Allegories of Underdevelopment: Aesthetics and Politics in Modern Brazilian Cinema. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 1997.

Xavier, Ismael. “Da violência justiceira à violência ressentida” Ihla do desterro: A journal of English language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies 51 (2006): 55–68.