Soviet Film Footage and Professional Practices (1941–1945)

Table of Contents

Soviet Film Footage and Professional Practices (1941–1945)

Towards a History of Soviet Film Records (Kinoletopis')

A Travelling Archive

Zinovii Tolkachov’s Graphics from the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek Death Camps

People with Disabilities as Nazi Victims on Screen and Paper

Forgotten: Film Documents from the Liberated Camps for Soviet POWs

Depicting Atrocities

Reflections on the Geography of the Holocaust Based on Soviet Film Footage

Soviet Footage from the 1940s and the Holocaust at Babyn Yar, Kyiv

Filming Auschwitz in 1945: Osventsim

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Tcherneva, Irina. “Soviet Film Footage and Professional Practices (1941–1945).” Research in Film and History 6 (2025): 1–50. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/23567.

The film footage recorded by the Soviets as they uncovered war crimes in the USSR, the Baltic states, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Germany and Hungary reveals a fundamental tension between media coverage of these acts of violence, which mainly focused on rousing emotions in viewers,1 and experts’ use of visual sources as evidence. Practices of using the footage as evidence were painstakingly developed during the war and started to gather particular momentum in 1943, when the first trials began in the USSR.2 Soviet footage, much like American and British footage, was filmed for use by the media, the military, forensic medical examiners and investigators, and was intended for both foreign and domestic audiences. This article explores the hybrid nature of such footage, which results from the competing demands that any attempt to produce filmic documents in times of war is subject to.

My discussion draws on an expanded corpus that has benefited from the recent identification of new filmed material. Most of the archives from 1941 have been lost. That year, chaos reigned due to the forced relocation of Soviet studios and factories in the East. The resettlement and restart of the film industry in November-December 1941 and the first wave of “de-occupied” territories marked a first milestone. Between November 19413 and January 1942,4 thirteen film crews were established whose task was to film on the front. They were placed under the administration of the Main Directorate of Documentary Films, headed by Fedor Vasil’chenko. Each crew consisted of seven to fifteen camera operators led by one of their peers. The crews operated until July 1945.5 In February 1947, the department that coordinated them was closed.6

From the material preserved in the archives, we know that these groups worked on around 330 sessions, which were wholly or partially focused on crimes against Jews, Roma, civilian victims of anti-partisan operations, disabled people and members of Soviet state and Party organisations.7 The activities of the camera operators left numerous and fragmented textual traces: filming reports, footage reviews, administrative correspondence and records, editing plans, supporting documentation from the camera operators themselves and their institutional autobiographies, memoirs and diaries. This article takes a pragmatic perspective to this documentation, seeking to understand the methods used by the film professionals to respond to violence and the ongoing efforts to build an overarching national discourse.8 Placing the visual registers used by the camera operators in their professional context, this article engages in dialogue with previous historiographical approaches to the filmed corpus. These approaches have focused on three main lines of inquiry: firstly, early documentation of the Holocaust in the USSR and, as a corollary, the ways in which the specific discrimination faced by Jews was effaced by universalising the victims;9 secondly, the role of visual documents in the trials of war criminals;10 and thirdly, propaganda policies.11

Examining the professional, institutional and social constraints under which filmmakers operated allows us to recognise the structural features that determined the shape and themes of the currently identified corpus. Therefore, we should not focus exclusively on the analysis of the decisions of the political authorities, but I propose to analyse an intermediary space that lies between the orders and the intentions of individual actors (extremely difficult to approach as historian) – a space where interactions were codified by the profession. How did filmmakers’ professional socialisation inform the way they approached visual evidence? What were the intended uses of the footage? And what were the relationships between the creators and commissioners of these works?

The analysis presented here is rooted in the social history of film production and engages with recent studies on images as a space of power relations.12 My aim is to question the rules and processes involved in composing a filmed, documentary perspective on extreme violence, and so I do not consider the work of writers and reporters who fashioned this plethora of images into narratives. I argue that the footage can be viewed as a reflection of professional and social exchanges relating to the discovery of war crimes, the temporalities of those exhanges, the things that were ultimately not recorded on film and the various barriers that were documented. This article contributes to a wider understanding of documentary historicity in times of war and strives to explore how politics shapes visual archives.13

Hesitant Institutional Attitudes Towards a Filmed Evidence

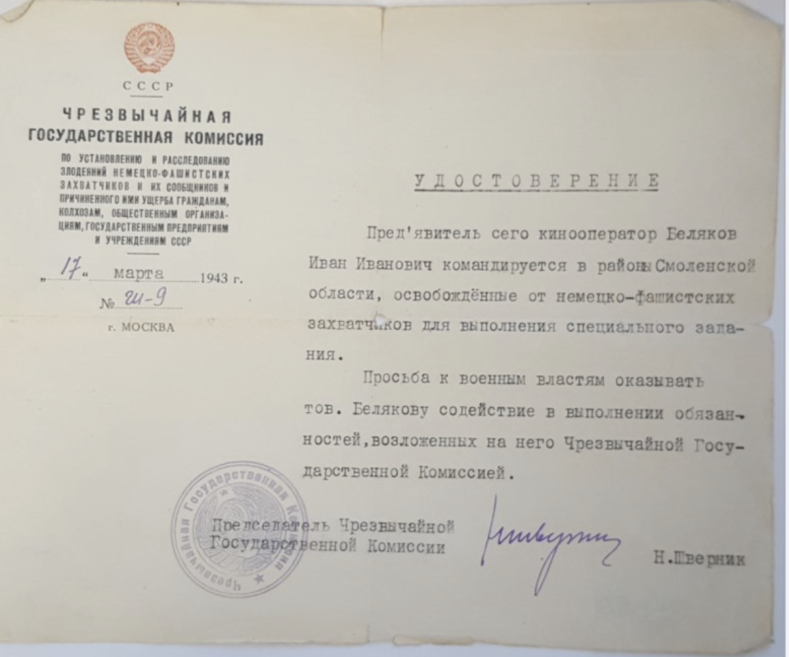

With the outbreak of World War II, the desire for a systematic use of images by executive, investigative and coercive bodies gained momentum. Following its creation in 1942, the Soviet Extraordinary State Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes (ChGK)14 made ever more frequent use of photography, although this practice was not institutionalised during the war.15 Regular circulars and directives reveal that there was pressing demand to standardise the filming of atrocities. Orders issued from August 1941 to December 1943 by the political department of the Red Army and the Main Directorate of Documentary Films encouraged camera operators to film investigators at work and build up a body of evidence, to follow orders from investigators and to film destroyed monuments and public buildings, execution sites and corpses, scenes of people identifying their dead relatives and any material evidence of humiliation and segregation. Vanessa Voisin has given a persuasive account of why such instructions emerged only hesitantly and late on.16 She also discusses the idea of creating an archive for the future (kinoletopis’) and notes that the ChGK’s work and the Kharkiv trial of 1943 were echoed in state institutions’ desire to codify and standardise the filming of atrocities. For Soviet documentary filmmakers, the path to the standardisation of evidence was a bumpy one. I will start by describing the administrative roadblocks that existed in a context of high institutional dependencies, before considering the professional culture that shaped these state-commissioned works.

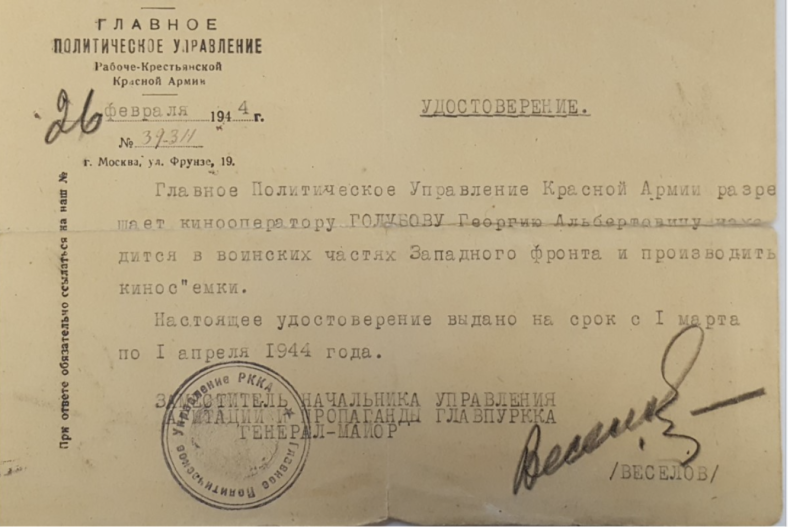

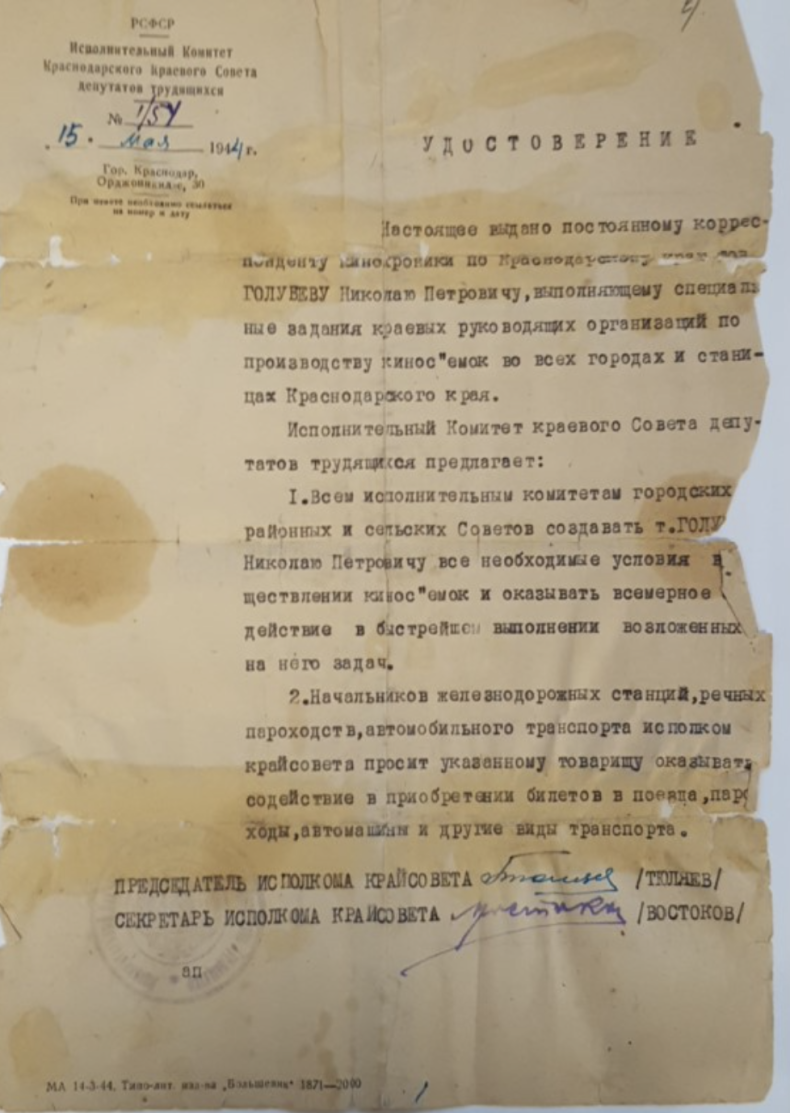

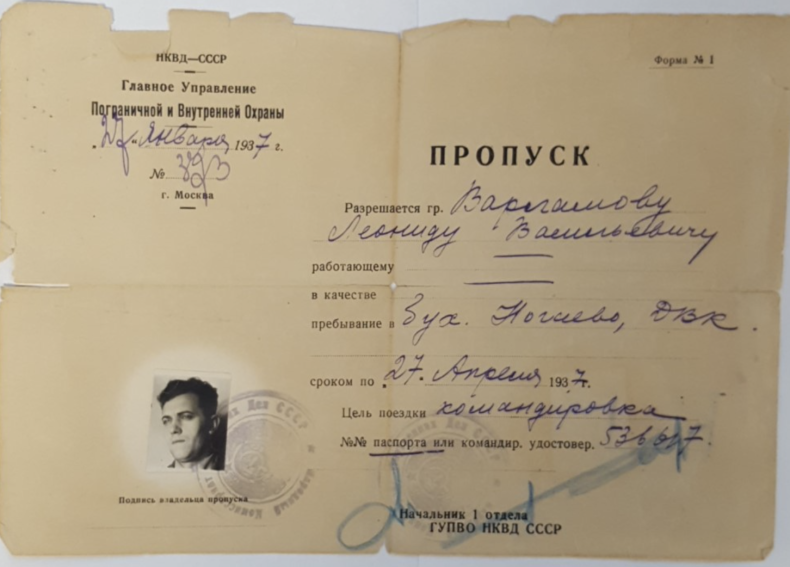

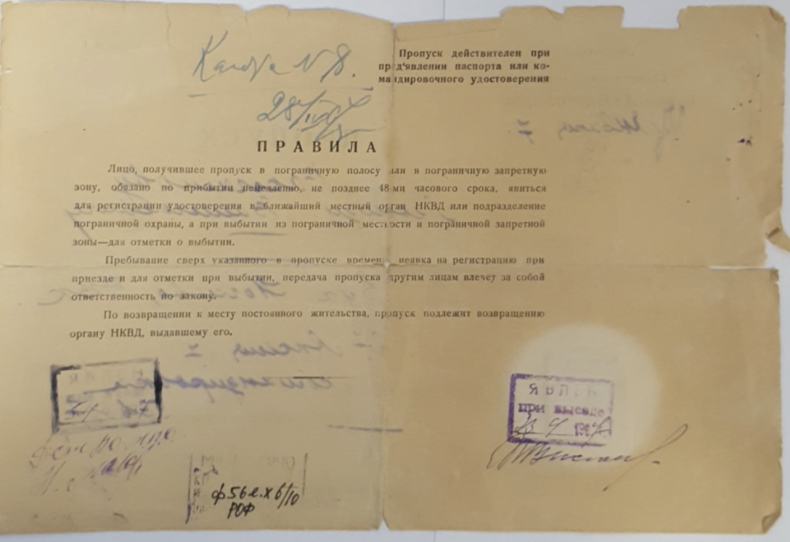

As civilian professionals working for the military, the camera operators were attached to regiments and authorised to film on an ad hoc basis.17 They worked in assigned geographical areas and were required to film without slowing down the regiment. The supporting documentation delivered to them specified their status and prerogatives, the state organisations that would assist with their work and the dates of their assignements. The army’s political directorate sometimes went so far as to stipulate what each camera operator was permitted to film (for example, firefights, sites of looting, prisoners, daily military life, the army’s political work and work with local populations and the running of soldiers’ clubs, newsrooms and the railways).18 This suggests that the thematic framework was strictly defined and the windows for filming short. Both the army and film crew leaders pushed camera operators to specialise (in types of weapons, in women and children’s suffering, etc.).19 This division of work contrasted with more flexible day-to-day practices, with camera operators in reality handling a variety of tasks.

In addition to the ChGK, the army, the regional authorities, the counterintelligence agency (SMERSH) and the commissariats of internal affairs (NKVD) and foreign affairs (NKID) were also involved. In several instances, the filmmakers noted that SMERSH had intervened in their work (in Ternopil’, Melitopol’ and Kharkiv and at the Stutthof (Sztutowo) concentration camp). The NKVD (in Kharkiv) and the NKID (for the shoots in the former Majdanek concentration camp) procured the camera operators’ visas, and on some occasions their representatives attended the filming sessions. The filming procedures and the thematic organisation of the footage were established laboriously, in a changing environment and with the involvement of various parties, all commissioning the same kinds of project but pushing for their own objectives.

At the beginning of their work at the front, a third of the camera operators tasked with filming war crimes already had experience making films for institutional use (such as military or medical instructional films).20 Some had called for the creation of (military or civilian) commissions of inquiry even before the ChGK was founded. For example, in December 1941, camera operator Evgenii Efimov reported that he had “asked the military leadership and local authorities to create a commission” and filmed the forensic examination of bodies, the writing of the report and so on.21 Moreover, one of the two investigations conducted between October 4 and early November 1943 into the murder of Jews and Roma in Mstislavl’ (Belarus) on October 15, 1941 by a punitive unit under the command of Field Marshal Krause22 was organised with the involvement and at the behest of filmmaker Moïsei Berov.23 This is already indicative of a correlation between the experience of cooperation with institutions outside the film sector reported by some filmmakers (including Efimov, Berov, Aleksandr Medvedkin and Vladimir Citron) and the initiatives they undertook to cooperate with these institutions without top-down supervision.

Observing Sites of Atrocities at the Scale of Filming Sessions

Based on an analysis that moved back and forth between textual and visual sources held in archives in Ukraine, Belarus, Estonia24 and Russia, I was able to build the most comprehensive inventory to date, with a total of 330 sessions.25 I documented these sessions using the following criteria: author, date, smallest geographical scale (village, camp, etc.), identifiers that the camera operator had placed on the reel and those added by the studio upon receipt, length of the footage, title and content as reported by the camera operators themselves, as well as any information on how the footage was used. The number of filming sessions that took place in each location indicates the vagaries of the front line’s movement, but also shows the importance that political authorities attached to media coverage of crimes perpetrated by the occupiers. For instance, there was one session in Liepāja (Latvia), thirty-three in the Auschwitz camps and fourteen in Kharkiv.

The collected data sheds light on the temporalities and geographic locations of these filming sessions. The camera operators recorded events of the Holocaust that are less well documented in other sources, such as executions by firing squads, crimes by Einsatzgruppen in areas under German military occupation or atrocities committed at smaller camps. Meanwhile, observing the better-known crime sites at this scale allows us to re-establish the timelines of the filming sessions, which were obscured by the archiving process, and to link the footage back to its specific contexts.

For instance, archival footage of the (temporary) liberation of Kerch in Crimea in January 1942 includes footage taken in different locations and at different times. The original, raw footage is mixed with edited material that was produced for documentary films. To understand this tangle, we need to distinguish the images from the filming sessions taken on different dates and involving different protagonists (filmmakers, state officials, filmed people). The first filming session, dated January 27, 1942, documented the slaughter of Jews in the Bagerovo anti-tank trench. From December 1 to 3, 1941 and on December 29, 1941, Einsatzkommando 10b, a unit of Einsatzgruppe D, murdered over 2,500 Ashkenazi Jews, as well as Roma and other individuals who had been named as partisans. During the second occupation, which began on May 19, 1942, many Krymchak Jews were murdered, though the Karaites were able to escape that fate.26 For the Bagerovo anti-tank trench alone, figures range from 2,500 victims, according to German sources, to 5,000, according to witness Joseph Weingarten, to 7,000, according to documents from the ChGK (which included other victim groups in its calculation). As early as January 1942 (that is, prior to the founding of the ChGK in November 1942), an investigative commission collected testimonies on the persecution specifically experienced by Jews, including confinement in the Kerch prison and executions.27 Several witnesses were survivors, who had been wounded but were able to climb out from under the corpses. There appears to have been great awareness among the population that these oppressive measures were mainly targeting Jews.28 Reporters and photographers who arrived at the time of liberation were also aware of this fact.29 Faced with a massacre of such an unprecedented scale, they looked for new narrative forms to convey the full horror.

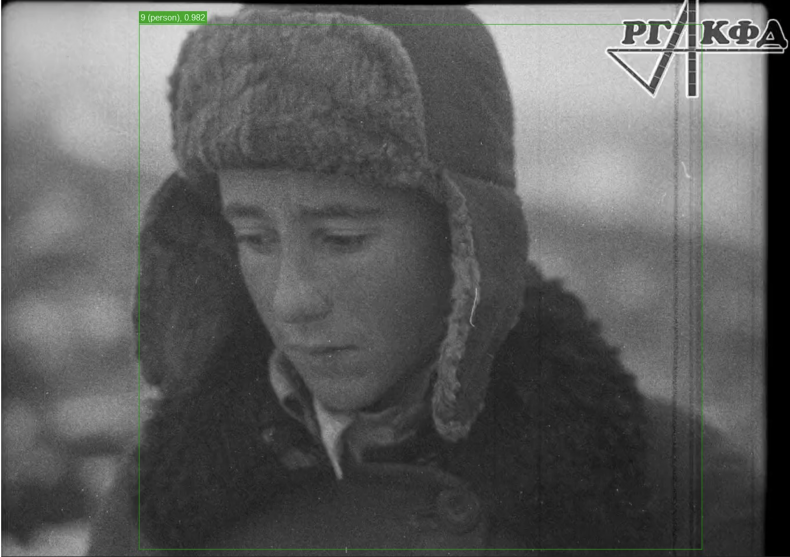

Camera operators Mikhaïl Oshurkov and Vassilii Mishchenko,30 who were working alongside the reporters and photographers, filmed Grigoryi Berman31 on January 27, 1942.32 He was a teacher of Jewish origin whose distress gained media attention through the work of photographer Evgenii Khaldej.33 The camera operators also tried to capture on film the pit’s dimensions and the exhumation of bodies, showing the victims in their undergarments.34 When viewing the footage, some signs of disrespect to the bodies being exhumed stand out. The camera operators also filmed the Soviets’ arrest of the Kerch and Feodosia starostas, who had been appointed by the Nazi occupiers35 and now stood accused, without any investigation, of the massacre of the Jewish population.36

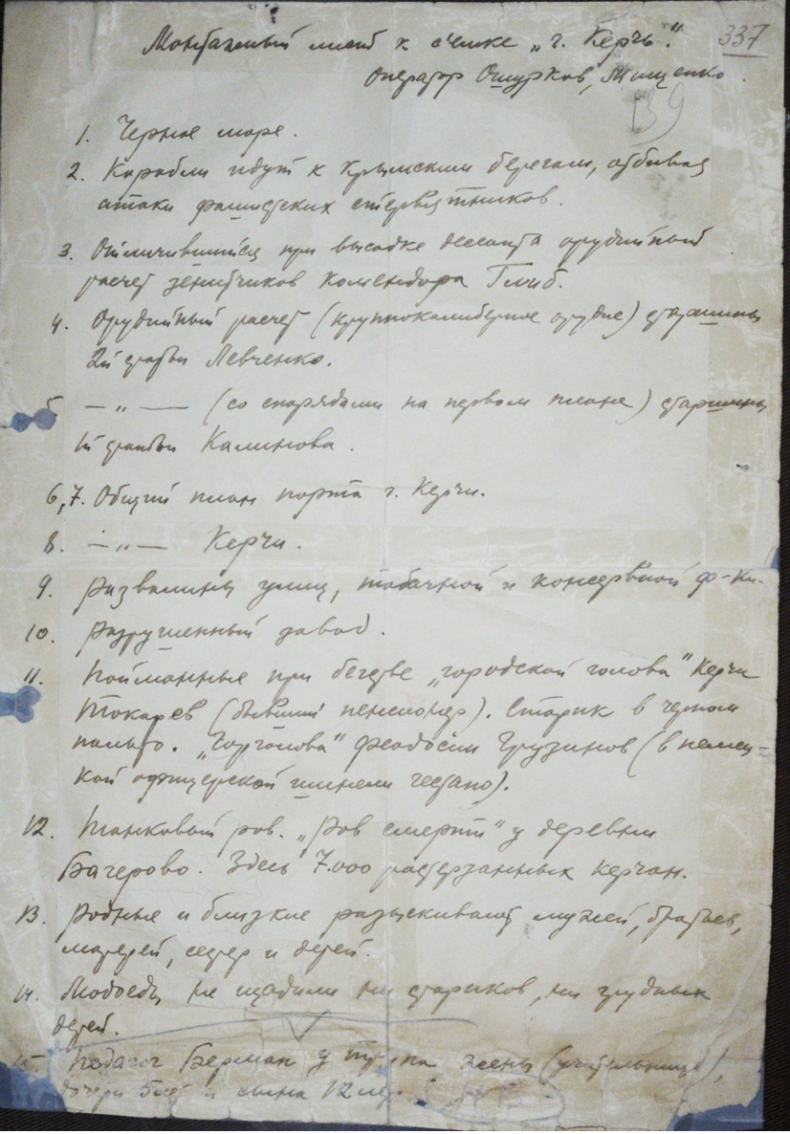

The other two crews from the Tbilisi studio filmed the rest of the footage. The first crew, whose members were Aleksandr Adzhibegashvili and Otar Dekanosidze, was led by film director Shalva Chagunava. Between January 29 and February 7, 1942, they filmed a commission of inquiry into the murder of 350 workers accused of acts of resistance at Komysh-Burun (18 km from Kerch) and Samostroy (on the outskirts of Kerch) in late December 1941. These investigations were not related to the persecution of Jews.37 The other crew, whose members were Levan Arzumanov and Vladimir Kilosanidze, recorded (without sound equipment) two Jewish survivors of Bagerovo between January 29 and February 8: Raissa Belotserkovskaia and her brother Iossif.38 Raissa explained to the camera operators how, wounded and crushed under the dead bodies, she was able to climb out of the ditch. She mentioned “thousands of Jewish victims.” Arzumanov and Kilosanidze also followed the trail of the two starostas named as ‘traitors’ and showed documentation that was supposed to prove their antisemitism.39 It is worth noting that these two crews were working under the supervision of Petr Moiseev, the chief of the political directorate for the Crimean front. Their thematic choices were therefore subject to his review and validation. Director Vladimir Mitrofanov also wrote a script for a newsreel on February 7, 1942 as part of his work for the second Tbilisi crew.40 Thus, the Tbilisi crews took a different approach from Oshurkov and Mischenko and drafted a script ahead of filming. The atrocities were not at the heart of the narrative. Rather, their main concern was to identify Crimea as a point of strategic military importance. This explains why the visual depiction of atrocity crimes is so understated.

Thus, both at the time of filming and when the archives were being compiled, the Holocaust was presented alongside other atrocities. This choice had political backing and emerged out of distinct institutional frameworks. Some of the images and footage were highly publicised, featuring in newsreels and a compilation film entitled WE TAKE REVENGE! DOCUMENTARY FILMS ABOUT THE MONSTROUS ATROCITIES AND THE VIOLENCE OF THE NAZI INVADERS!41 The Jewish identity of the victims was downplayed. The testimony of the two Bagerovo survivors was not used either during the war or in the kinodokumenty compilation film that was shown at the Nuremberg trials. The latter also did not include footage of acts that could be deemed disrespectful to the dead. A film of the murders that were committed at two other filming locations was never shown to the public, nor was one showing the presumed collaborators. Moreover, the order of the filming sessions was changed when the material was archived, and this changed order was maintained when a copy of the Kerch film sessions was made for the Ukrainian archives in 1961.42 The information stored in the film archives was selected and compiled across multiple points in time, adding successive layers of meaning.

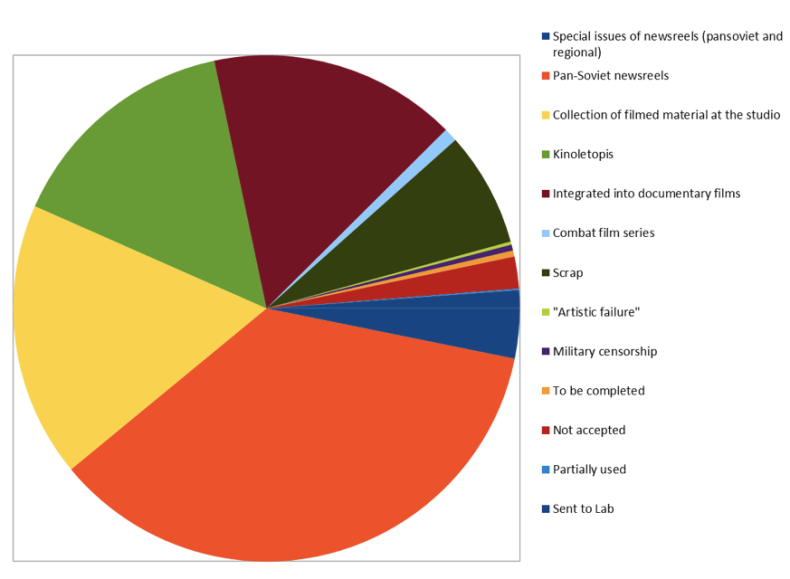

The initial footage was thus broken up over the course of several edited versions and under the management of various institutions. Due to the multiple filing stages that the preserved film footage went through (firstly, during transit from the war front to the lab; secondly, at the lab; thirdly, at the central studio; fourthly, in the archives (so as to build up the kinoletopis’ film footage collection); and, fifthly, at various Soviet archives after the war), up to half of the material recorded in one place could be discarded, lost or dispersed.43 A review of the filmed items received by the Central Studio of Documentary Films from May 1942 to July 194344 and the reports sent by the film crews responsible for the newsreel department helped me to trace the footage’s migration. Initially created to evaluate camera operators, the review gives indications of how each piece of footage was used. Grouping these mentions by type of use can help to situate the footage currently available for this period (see Figure 9, which provides a diagram based on the number of units (siuzhety)).

These categories, which were defined by the studio’s employees, partially overlap. In all likelihood, any piece of footage could be arbitrarily assigned to the categories “artistic failure” or “filming to be completed” or to the seemingly all-encompassing “not accepted.” Footage that was to be placed in the studio’s “film collection,” “censored” or discarded was labelled “artistic failure” and so not preserved in the archives. The diagram gives us an idea of the volume of footage that is likely lost forever, as well as the main uses to which the footage was put: namely, incorporation into films and newsreels (central and local) and the creation of a kinoletopis’ and a film library at the central studio. This grading grid, which was applied to filmed material, constitutes an essential space, typifying one way in which power structures shaped documentation. While undertaking an “archaeology” of documents – that is, scrupulously placing the material in its historical context – is a necessary task for any archive, doing so is especially challenging for film documents due to the misleading impression of immediacy that they create. Our case studies were intended precisely to help us meet that challenge.

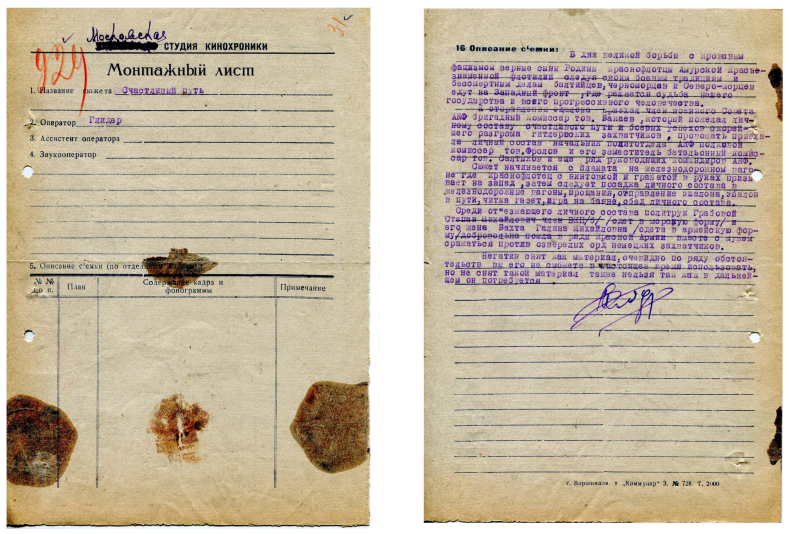

Filming Reports - Spaces for Reshaping Observed Facts

“In each film canister [from the front], there was an explanatory note. Sometimes, it was typed out, sometimes it was just a piece of paper with a few pencilled scribbles.”45 That was how Jurij Karavkin, a reporter who was tasked with reviewing footage during the war, described the caption sheets sent by camera operators to accompany their film reels. These documents would usually indicate the camera operator’s name, the length of the film footage in metres (each camera operator was given his/her own allocation of film or stock, and so could not use more metres of negatives than he or she had been assigned), the title of the footage, its subject, indications of location and time, the names of the people filmed, a list of the shots with indications of scale, weather conditions that would have affected the quality of the footage and other specific circumstances.

It was a great challenge to standardise these reports so that the footage’s evidentiary nature could be coded. Analysing them reveals the tensions between the visual registers adopted by different filmmakers. As well as a growing number of directives from the Red Army and the Ministry of Cinema, 1942 saw attempts to impose a specific standard on caption sheets. Filmmakers were encouraged to break up information into spatial and temporal facts about the film shots’ content, descriptions of the techniques used and details about the people filmed. However, the filmmakers were resistant to filling out these forms. They would group all the information in a single field, and sometimes expressed their spontaneous reactions or made patriotic and propagandistic statements (Figure 10). In doing so, they signalled a reluctance to compartmentalise the information captured through the camera’s gaze. During the war, reviewers in the Central Studio of Documentary Films asked camera operators to write detailed, accurate caption sheets, including descriptions, and not to generalise or fall into psychologising interpretations.46 Instead, they should write about the film’s specific content. The recurrence of these requests suggests that they were generally ignored.

The function of the caption sheets was in reality neither institutionally fixed nor clear to the camera operators. It is revealing that the camera operators referred to the sheets variously as the directory or editing list, the filming and editing directory, the filming and editing plan, the subject plan, the subject editing plan or even author’s intention. The diversity of terms indicates the many ways that camera operators verbalised the things they had seen. In some cases, the author of the caption sheet would focus on describing what had captured on film and so the document was similar to a report. In others, the author focused on how the material was organised to meet a specific purpose. The term “author’s intention” expressed a degree of reflectivity, and was used to signal that camera operators wanted to distance themselves from objectively observable facts and provide their own interpretation.

These opposing tendencies can be illustrated by two examples. Firstly, there is a report written by Arkadij Zeniakin, which aimed to be as precise and objective as possible. Zeniakin filmed the Stutthof camp in Gdansk (which was incorporated into Poland after the war) on June 19, 1945. He noted in his report that he had not been authorised to film before the SMERSH investigation was concluded, which happened two months after the camp was liberated. He said he had paid great attention to the Jewish victims47 and filmed a railway carriage where gas had been used to asphyxiate the victims.48 He also helped to identify the captured and interrogated collaborators that he had filmed.49

A markedly different approach was taken in a report submitted by Roman Karmen, who had been dispatched to Lublin by the political authorities to film the Majdanek camp. He started work on July 28, 1944, five days after the camp was liberated. Several days before his arrival, other experienced print journalists (Vassilii Grossman, Aleksandr Werth, Konstantin Simonov, Boris Gorbatov and Evguenii Kriger), ten photojournalists, eleven Soviet filmmakers and four Polish filmmakers started gathering evidence of crimes committed in the city of Lublin and in Majdanek. From the outset, Karmen strove to capture a complete picture of the crimes that had been committed and to define the nature of the camp. It is revealing that his film report50 does not allow the viewer to locate where and when the individual shots were taken, but rather builds a narrative “on the basis of the images.” Generalisations of that kind were bound up with how he conceived of his work as a reporter.51 Karmen’s work emphasised the varied nationalities of the detainees and the industrial nature of the extermination. He explained the process of gassing and the gases that were used (knowing that at the time, images of Zyklon B and the crematorium were not yet comprehensible to viewers). He also filmed traditional portraits with an inmate from Kyiv and Soviet prisoners of war.52 His entries on the caption sheets are typical expressions of a “pre-editing” (snimat’-montazhno) approach,53 with suggestions being made for the later editing process.

There are many traces of attempts to “pre-edit,” including by individuals who had little interest in shaping the profilmic event ahead of its filming. For example, caption sheets contained advice on editing the footage or written commentaries about the future voice-over or, alternatively, humble assertions that this particular footage was not sculpted as a piece of newsreel in its own right. The reports were interspersed with highly personal language or signs of strong emotional involvement, indicating the hold that narrative codes had over their authors. That can be witnessed, for example, in curses against the enemy or in the choice of language to describe Wehrmacht soldiers (“hunting,” “wild beasts,” “extermination”). Such instances are especially apparent when camera operators were trying to adapt to the film director’s expectations (in particular, in filming reports marked “for Dovzhenko”). After filming evidence of a crime in Chyhyryn, camera operator Nikolai Topchij immediately specified that one part of the footage was meant for Oleksandr Dovzhenko while the other was for the newsreels,54 which implies that these required different styles.55 Sometimes, conversely, caption sheets broke away from public-oriented narratives and comments intended to be voiced on screen, and instead adopted a style closer to a personal diary or document. Over the course of these developments, some camera operators learned to gain more autonomy: for example, labelling a filming session with the name of the municipality would give them more flexibility than if they took a thematic approach. The number of films relating to observations of atrocities that were labelled with a plain title grew exponentially.

The oscillation between an emphasis on the descriptive, which was likely to give more flexibility to the visual treatment of the footage, and an emphasis on profilmic organisation echoes the tension between dramaturgical aspirations and an impulse to standardise visual evidence that emerged within the film authorities. The standardisation desired by the authorities was fragmentary and non-linear. Consequently, caption sheets should be viewed as spaces where choices were sometimes explained and justifications were expressed for what could or could not be filmed – in other words, as spaces for expression and for ongoing creation of a framework for professional procedures. The caption sheet also, to some extent, allowed camera operators to preemptively influence the distribution, even though in most of their testimonies they indicated that they were rarely able to see it in cinemas.

The Weight of the Professional Ethos

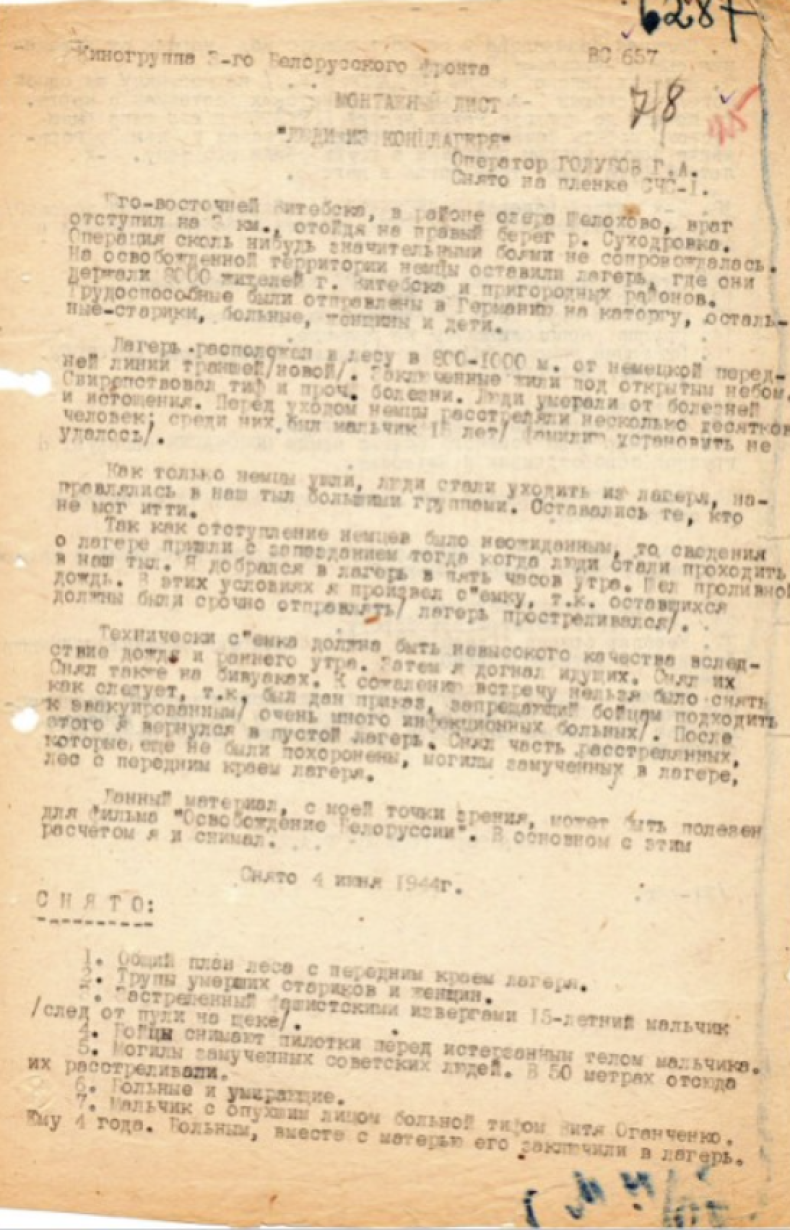

Not only was the institutional impulse for the production of visual documents late and uncertain, but professional norms also discouraged a conception of camera operators’ role as being simply to record the raw footage. From evaluations and reports issued by film crew leaders and sent to the newsreel manager, it appears that the filming of atrocity crimes was relatively infrequent; for instance, they were the subject of only two out of the thirteen films shot by a crew between February 15 and March 31,56 and three out of the fourteen shot by another crew in the North Caucasus between December 1942 and mid-January 1943.57 The bulk of their filming was dedicated to soldiers, partisans and POWs. This might seem paradoxical, given the symbolic benefit the Red Army could derive from denouncing the enemy’s crimes, but the archives indicate how cultural conceptions of the camera operator’s role conflicted with this goal. For example, Georgyi Golubov filmed an open-air camp for civilians near Liozna58 in the Vitebsk region in Belarus on June 4, 1944 (Figure 12). He estimated there were 8,000 victims, and highlighted the high mortality rate (which was due to diseases) and the high numbers of children. When describing the circumstances under which he filmed the footage – at five in the morning, in the rain, in defiance of an order not to approach contagious ex-inmates – he tried to explain his approach.59 At a professional meeting on September 15, 1944, he stated that he was aware that his filming would be criticised “because cannons do not fire there. But they don’t take into account the fact that I crossed a minefield to film this.”60 Paradoxically, by filming evidence of crimes, the camera operator was likely to be seen as a “shirker” because he was not filming on the front line. Archival materials from 1944 mention accusations, suspicions and even denunciations against camera operators who were allegedly or actually moving away from filming on the front lines.61 This type of label was undeniably disgraceful. For instance, film director Oleksandr Dovzhenko stated : “One has to concede that camera operators have a lust for life that extends beyond the situation officers are experiencing on the front line.”62 In Golubov’s case, his colleagues appreciated his way of filming for its immediacy, and the recently appointed head of the Central Studio of Documentary Films, Sergei Gerasimov, wrote of his footage: “The striking thing is that the earth is still smoking. Everything has just happened.”63 As such, it was not the subject but the way it was filmed that led it to be selected for and edited into a film about Vitebsk.

The wartime production system was more geared towards filming events and action on the front (subject to constraints of secrecy). In 1944, bonuses were created to reward this type of filming (whereas none were put in place for filmed reports of war crimes).64 This also affected what was likely to be included in films and newsreels, and how much interest camera operators had in filming evidence of crimes. For example, in his correspondence with camera operator Dimitrii Dal’skij in January 1943, film crew leader Mark Troianovskij (who later became the head of the front-line film crew department) ordered Dal’skij to reduce the amount of “static images” (that is to say, footage of atrocities, destruction and trophies) and to give priority to filming battles,65 even though on other occasions he requested that Dal’skij focus on capturing evidence of specific crimes on film.66 According to Troianovskij, depictions of crimes were not enough to engage viewers’ interest by themselves, and so if atrocities had to be shown, it was best to mediate them through certain themes: the destruction of heritage, historical comparisons, etc. This demonstrates that the film sector was moving away from its earlier practices of evidence-gathering. In April 1944, Leon Saakov, the new head of the department responsible for coordinating the crews filming at the front,67 and editor-in-chief Nikolai Kemarskij wrote that they had liked a film from Viktor Muromtsev and Jakov Smirnov, “Tragedy in the region of Pskov,”68 which documented executions and arson in the villages of Pikalikha, Zaroi, Kriakusha and Karamyshevo. The reviewers noted as a reminder that it was especially important for the Soviet public, who were familiar with the ChGK reports published in the press, to see their visual incarnation rather than the raw data. The versions of the footage edited for the public needed, the reviewers said, to include “allegories” similar to the “literary comparisons” or “genre elements” found in journalism. They claimed that showing a situation with a focus on a particular element (for instance, a burnt kitten next to smoking ruins) would rouse strong emotions in the audience.69 This aspiration among professional circles to do more than simply present the raw facts could sometimes result in them downplaying or excluding information about the murders. For instance, Mark Troianovskij and Nikolai Kemarskij admired the filming session that was carried out in the devastated city of Iziaslav,70 writing that it was “laconic and tactful” yet “broad in scope” at the same time, since camera operator Samuil Davidson had successfully combined shots of murdered victims, a museum turned into a prison, burnt houses and wrecked tractors.71 When a film sequence managed to visualise a dichotomy in a way that was easily comprehensible to audiences, it tended to be met with appreciation by the reviewers.72

We can thus delineate the framework in which camera operators were expected to work. The push toward conciseness went hand in hand with an incentive to film “expressive portraits” and refrain from taking multiple shots of the same thing.73 The reviewers would repeatedly stress that the camera operators should demonstrate an attempt to control the situation, not repeat themselves, and they were not allowed to do multiple takes (for instance if there were problems with equipment). Film professionals appear to have thoroughly incorporated social constructivist approaches into their practices, as reflected in camera operators’ ability to immediately identify the dialectics of a sequence of visual elements, and so avoid “haphazard” or “poorly thought-out” shots. These high expectations could also be linked to factors as simple as a lack of film stock or the low sensitivity of film (which could restrict a filming session to just two or three hours on days with bad weather). In the production system, the studio kept records of the length in metres of footage filmed by each filmmaker and of what was included in newsreels or films. This productivist perspective was ubiquitous in reports by Karavkin on the heroic figures of front-line camera operators.74 In these individual portraits, broadcast by the Sovinformbureau, the camera operators’ “output” was systematically listed and they were woven into glorifying narratives.

The Layers of the Invisible

Several cumulative constraints that weighed on the camera operators can be discerned in a part of the corpus containing information about the crimes that is now almost entirely lost. Some of this footage can no longer be located, but surviving caption sheets confirm that it did once exist. From these sheets, we learn, for example, that in the spring of 1944 Vladimir Citron filmed a camp for Jews “established by Romanians” in the Vinnytsia region.75 Citron repeated the investigators’ information that there were 7,000 to 8,000 victims, and interviewed Jewish survivors whom he names as Mania Pliam and Meilah Aglesman.76 In other sheets, we discover that in Zamość, a Polish town in the Lublin district in the “General Government” region (as German-occupied central Poland was called), Anatolij Pavlov and Aleksandr Vorontsov filmed the Rotunda prison where, they noted, “10,000 Poles and Jews were murdered.”77 This nineteenth-century stronghold was used as a transit and POW camp, where around 8,000 Jews, Roma, partisans and Polish and Soviet soldiers were murdered.78 A review of a filming session in Skala-Podilska (a former Polish city in southern Ternopil oblast that was annexed by the Soviets in 1939, then occupied by Romanian and German forces) from the same period indicates that Kenan Kutub-Zade and Grigorij Ostrovskij went there to record the testimony of a family of Jewish survivors and to film Jewish houses that bore the marks of the occupation.79 Only three or four Jewish families from the town had survived. In April 1944, photographer Vladimir Yudin took a picture of the Stachel family80 (Figure 13). These locations and many more can be added to the list of sites where the Holocaust left a visual mark.

Currently, unidentified material whose existence is only attested by textual documents represents 21 percent of the corpus. Footage that could not be found in public archives prior to 2021 may have been conserved in institutional archives that are presently not open to researchers.81 When the ChGK was created, the film authorities oversaw the inventory process and the previously filmed footage that was to be transferred to the commission to deal with.82 Another portion of the footage was immediately earmarked for the commission, and some filming sessions were reserved for the counterintelligence service. This process took place behind closed doors, without the involvement or knowledge of the local population.83 Moreover, shots of the atrocities were sometimes taken from reels filmed in liberated municipalities and assembled into compilation films.84

Textual documents that were left by the filmmakers, including both ones produced for the benefit of their colleagues and ego-documents,85 testify to the wealth of information to which camera operators had access and to how that access was curtailed as soon as the relevant evidence had been captured on film. In 1942, camera operators often reported that they were made aware of the atrocities by witnesses. In one of these many instances, during a filming session in Rostov-on-Don in February 1943, Boris Shchadronov and Mikhail Poselskij identified forced labourers, as well as locals murdered in a prison and a ditch filled with bodies. They wrote in their note: ‘The entire Jewish population was killed or transported to an unknown location.’86 They were often unable to record tangible evidence on camera (since villages and camps had been emptied of their populations,87 bodies were decomposing88 or had been removed for sanitary reasons89) and wondered how to capture that emptiness on film.90 A lot of information could only be communicated verbally. Camera operators often made the choice to present such testimonies on screen, even though most of the time they did not have sound equipment.91 But what could such testimonies reveal about, for example, the murder of 8,000 Jewish residents in Mariupol in October 1941 if witnesses were filmed two years afterwards?92 Or how could camera operator Abram Kozakov film soil in a way that showed how it had been turned over by buried victims?93

Besides, on multiple occasions, camera operators did not hesitate to stress that the victims were Jewish. More importantly, textual documents shed light on the sensitive information camera operators were privy to regarding the persecution of Jews, which was not captured on film. For instance, in Uzhhorod94 in Zakarpattia, filmmaker Vladimir Sushchinskij wrote: “Having heard the sound of the tanks, a crowd of Jewish survivors arrived. Starving, ragged, wearing yellow armbands, they rose their arms and approached, begging not to be shot.”95 The scene described here, which stands in stark contrast to the officially sanctioned images of cheerful greetings and should prompt extreme caution about this testimony, does not seem to have been captured on film. In some instances, camera operators who had set themselves a specific theme to film missed other evidence. For example, Mamatkul Arabov and Arkadij Chafran filmed German POWs and described the atrocities committed in the villages of Kolky and Manevychi (Volhynia), which before 1939 had had a rich Jewish culture and so took a heavy toll during the Holocaust.96 Upon reviewing these filming sessions, Troianovskij and Kemarskij criticised the fact that this information was only reported verbally and then noted in the caption sheet. According to them, since the information was not visible in the footage, the latter lost “its evidentiary power.”97 To counter such criticisms, some camera operators indicated in their caption sheets that it would be relevant to draw segments from the stock of footage that was kept at the studio or to use images filmed in other contexts to flesh out their fragmentary material.98

Early 1944 marked a significant turning point for the widespread uncertainty among camera operators about what could be included in newsreels. Until then, as noted earlier, the production system had favoured filming on battlefields. But in 1944, film crews learned of a circular from early December 1943 that allowed them to film for posterity, without adjusting filming to the distributions’ expectations, and to show the atrocity crimes specifically.99 Often, as they were reeling from shock, the camera operators would grab their camera to film, protecting themselves by creating distance through the device on their shoulders. But the shock triggered by the sight of human remains could also make filming impossible, as indicated in some of the camera operators’ testimonies. When the situations were finally filmed, the idea that the camera operators could bring their personal perspective to the filmed material widened the scope of what they could consider “filmable.” In his memoirs, filmmaker Anselm Bogorov explained how in February 1945 his film crew crossed paths in Przemyśl (a Polish town that was divided between Germany and the USSR under the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact signed in August 1939100) with a group of “those few Jews who survived from Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia and several Gypsies”:

In Przemyśl, they lived in the cellar of a half-destroyed building, having fitted it for accommodation to the best of their ability. Having heard from the adjutant that we had no roof over our heads, they invited us to their house and insisted we come over. We stayed with them for two days. Of course, we knew of the torture inflicted on prisoners in the fascist concentration camps, but our knowledge was only theoretical. And now, here we were, sitting at the same table as people who had suffered from these torments. They showed us their torture marks, the numbers engraved on their bodies. I was struck by their attitude towards everyday life which remained inaccessible in my mind. They looked at life as people who had been on the other side, a side from which there is no return.101

Paradoxically, at the end of the war, this camera operator from the Leningrad front line, who was then working at the front in Volhov, in Karelia and in the area of the 1st Ukrainian Front, said that he had “exclusively theoretical knowledge” of the crimes. It is highly likely that he had already been confronted with the witness footage. But in this case, his inability to cope with the materiality and immediacy of his sensitive testimony raises the question of the previously codified relationship between filming and filmed that, on this occasion, imploded due to the time spent with the survivors over two days and two nights – an exceptionally long period. This direct and personal confrontation with first-hand witnesses took him out of his professional comfort zone. Moreover, camera operators were clearly more exposed to atrocity crimes perpetrated by the occupiers than the visual materials alone indicate. The corpus of film footage currently available in the public archives includes only a fragment of these materials, which differ from what viewers were shown at the time. The two sets of materials can be distinguished based on the camera operators’ written notes. At each stage of this “framing” of information, the political dimension crept in. This highlights the professional conditions that influenced the footage they recorded of the crimes perpetrated by the occupiers.

Conclusion

The eruption of death on Soviet screens gave rise to official attempts to codify its depiction. This evolution was neither linear nor completely realised, and the wide array of output that stemmed from contradictory institutional guidance resulted in the hybrid nature of the documentary footage we have examined here. Looking at the filmmakers’ practices opens up avenues of micro-historical research on the exchanges between filmmakers, witnesses, survivors and investigators, and highlights the ways in which politics, as expressed in the institutions’ and film professionals’ day-to-day interactions, moulded the film archives. The undeniable political censorship was one stage in the standardisation of visual evidence of the crimes. The film industry’s unique professional culture was certainly disrupted by the exceptional circumstances of this armed conflict. Nonetheless, the value attached to distancing through art, the filmmakers’ desire to gain control over profilmic events and the need to take a holistic approach to documenting the occupiers’ crimes continued to play a significant role, affecting how camera operators interpreted administrative injunctions to produce descriptive, objective films. The scarcity of material resources and the dialectical tradition that was supposed to dominate the production of ideas and images often led to generalisations.

The analysis presented here has attempted to elucidate the epistemological linkages among the institutional incentives and hesitations and the various stakeholders involved in filming evidence of crimes. This footage was the product of a collective effort. Looking at the constraints under which it was produced, which were rooted in a certain institutional culture, reveals how it went through several stages of sorting and framing. Consequently, the raw footage has an evidentiary value that is lost in the edited films. At the same time, the requirements imposed by the institutions involved in the investigations and a culture of secrecy impacted on understandings of visual narratives. In the footage, we can discern traces of the filmmakers’ never-ending search to achieve an acceptable distance from survivors, locals, reporters, military officers and investigators when filming evidence of extreme violence.

- 1

Valérie Pozner, Alexandre Sumpf and Vanessa Voisin, ed., Filmer la guerre: les Soviétiques face à la Shoah, 1941–1946 (Paris: Mémorial de la Shoah, 2015); Vanessa Voisin, “De la paix à la guerre, de la fiction au documentaire: Alexandre Dovjenko et Youlia Solntseva,” Conserveries Mémorielles, special issue The Cinema Goes to War: Screens and Propaganda in the USSR (1939–1949), ed. Valérie Pozner and Irina Tcherneva, 24 (2020), https://journals.openedition.org/cm/4549.

- 2

Vanessa Voisin, “Soviet Footage of War Crimes, 1941–1946: Between Propaganda and Judicial Evidence,” in Defeating Impunity: Attempts at International Justice in Europe since 1914, ed. Ornella Rovetta and Pieter Lagrou (New York: Berghahn Books, 2022), 149–150.

- 3

The date on which the film crew for the south-west front was established. Moscow Film Museum (CM), Central Studio of Documentary Films collection, f. 56, op. 1, d. 60-1, ll. 27–28.

- 4

CM, f. 56, op. 1, d. 58-17, 2 ll.

- 5

CM, f. 56, op. 1, d. 58-18, l. 4.

- 6

CM, f. 56, op. 1, d. 26-90, l. 1.

- 7

In most cases, the Visual History of the Holocaust project has excluded POWs from this visual collection, since the focus of the project has shifted to civilian victims.

- 8

A case study by Vanessa Voisin analyses the professional relationships of one film crew. Vanessa Voisin, “Mark Troïanovski, chef d’équipe cinématographique sur le front, 1941–1945,” in Combattre, survivre, témoigner: Expériences soviétiques de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, ed. Emilia Koustova (Strasbourg: Presses universitaires de Strasbourg, 2020), 129–160. See also Victor Barbat, Roman Karmen, la vulgate soviétique de l’histoire. Stratégies et modes opératoires d’un documentariste au XXème siècle, doctoral thesis (Paris: l’Université Paris 1, 2018).

- 9

Jeremy Hicks, First Films of the Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 1938–1946 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012); Valérie Pozner, Alexandre Sumpf and Vanessa Voisin, “Que faire des images soviétiques de la Shoah?” Revue d’histoire du cinema 1895, 76 (2015): 8–41; Natascha Drubek-Meyer, Filme über Vernichtung und Befreiung: Die Rhetorik der Filmdokumente aus Majdanek 1944–1945 (Wiesbaden: Springer, 2020).

- 10

Voisin, “Soviet Footage of War Crimes,” art. cit.; Nathalie Moine, Les vivants et les morts: Genèse, histoire et héritages de la documentation soviétiques des crimes (forthcoming).

- 11

As per the above-mentioned research.

- 12

See, for example, David Shneer, Through Soviet Jewish Eyes: Photography, War and the Holocaust (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2011); Sylvie Lindeperg, Nuremberg: La Bataille des Images (Paris: Payot, 2021); Ania Szczepanska, Une histoire visuelle de Solidarność (Paris: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’Homme, 2021); Tal Bruttmann, Stefan Hördler and Christoph Kretzmüller, Un album d’Auschwitz: Comment les nazis ont photographié leurs crimes, trans. Olivier Mannoni (Paris: Seuil, 2023).

- 13

This article was translated by Delphine Pallier, to whom I would like to express my gratitude, as well as to the review's editorial team and to the VHH project colleagues.

- 14

The complete name is Extraordinary State Commission for the Establishment and Investigation of the Atrocities of the German Fascist Invaders and Their Accomplices and the Damage They Caused to Citizens, Collective Farms, Public Organizations, State Enterprises and Institutions of the USSR.

- 15

Irina Tcherneva, “Le crime dans l’objectif: photographie de la Commission extraordinaire d’État (URSS, 1943–1945),” in Photographier la violence extrême: Témoigner par l’image, ed. Paul Bernard-Nouraud, Luba Jurgenson and Irina Tcherneva (Paris: Petra, 2024), 225–271.

- 16

Voisin, “Soviet Footage of War Crimes,” art. cit., 151–152, 159. Translations of these instructions can also be found in the catalogue of the exhibition: Pozner et al., Filmer la guerre, 12.

- 17

CM, f. 56, op. 1, dd. 6-4 and 6-5.

- 18

CM, f. 56, op. 1, d. 47.

- 19

For instance, during a filming session in Königsberg by Aleksandr Medvedkin, the then leader of the film crew of the 3rd Belarusian Front. CM, f. 56, op. 1, 9/10, February 5, 1945, ll. 7–8.

- 20

This figure was calculated by identifying the camera operators who had filmed war crimes on the basis of their personal files held at CM, f. 56, op. 2, supplemented by the catalogue prepared by Aleksei Deriabin, Sozdateli frontovoi kinoletopisi: Biofil’mograficheskij spravochnik [The Creators of Film Annals at the Front. Biographical and Filmographic Catalog] (Moscow: Gosfilmofond, 2016).

- 21

Quote from Valeri Fomin, ed., The Cost of Framing the Scene: Soviet Filmed Chronicles of the War, 1941–1944 [Tsena kadra: sovetskaja frontovaja kinokhronika, 1941–1945] (Moscow: Kanon+, 2010), 157.

- 22

Geoffrey P. Megargee and Martin Dean, eds, Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945, Volume II: Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe (Washington: USHMM, 2012), 1706–1707.

- 23

Caption sheet no. 1520, undated, 450 m.

- 24

These filming sessions were heavily centralised. The material was mainly preserved in Moscow. By contrast with Ukraine, Belarus and Estonia, some former Soviet republics that have since become independent, such as Lithuania, did not receive copies from Moscow after 1991.

- 25

One session corresponds to one or more reels filmed over a short period in a single location by two camera operators. On rare occasions, the material that was submitted included footage filmed in two different locations. Being able to consult the whole set of caption sheets currently available was of crucial importance to identifying these locations. That was made possible by a collection of caption sheets from camera operators sent to the Soviet front that was acquired by the Visual History of the Holocaust project in 2020 from private collector Valeri Fomin. Originally, this material was held by the Russian Central Studio of Documentary Films (CSDF). The collection contains detailed descriptions of footage that camera operators sent from the various fronts of World War II. Valeri Fomin has published a selection of these caption sheets in Fomin, ed., Tsena kadra [The Cost of Framing the Scene] and “Plach’te, no snimaite!”: Sovetskaia frontovaia kinohronika 1941–1945 gg. [“Cry but keep filming!” Soviet Documentaries from the Front 1941–1945] (Moscow: Gosfilmofond, 2018).For the purposes of the Visual History of the Holocaust project, we compiled an analytical selection of 374 sheets dealing exclusively with the filming of atrocity crimes. The original documents are either handwritten or typescripts. They were signed and dated by the filmmakers and the filming locations specified. Another collection, containing 169 sheets, completes Valeri Fomin’s collection and is held at the Russian State Archive of Film and Photographic Documents (RGAKFD).

- 26

On this differential treatment, see David Shneer, Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 28–29.

- 27

See documents from the Extraordinary state commission, records of trials that took place in 1947, 1961 and 1972 and testimonies collected by Yad Vashem: https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/untold-stories/killing-site/14626711-Bagerovo-Anti-Tank-Trench. See also the testimonies collected from Krymchaks and other villagers in Kerch by Yahad – In Unum: 113U3, 114U3, 115U3, 116U3, 117U3, 118U3, 119U3, 1680U36, 268U7, 1676U36. GARF 7021, op. 9, d. 38. The estimate of 7,000 victims was repeated in the press and in the film shown by Soviet prosecutors during the Nuremberg trials, and later in scholarly works.

- 28

For example, see the interview with Zalman Grinberg, 2012, preserved in the Blavatnik Archive: https://www.blavatnikarchive.org/item/14355?relevant=8,9,10,12, 00:21:43–00:26:15.

- 29

Shneer, Grief, 31–60; Maxim D. Shrayer, I Saw It: Ilya Selvinsky and the Legacy of Bearing Witness to the Shoah (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2013); Harriet Murav, “‘Poetry after Kerch’: Representing Jewish Mass Death in the Soviet Union,” in Soviet Jews in World War II: Fighting, Witnessing, Remembering, ed. Harriet Murav and Gennady Estraikh (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2014), 151–167.

- 30

Caption sheet, “The City of Kerch,” no identifier. RGAKFD 6067-b, 2 ll. The filmmakers repeated the figure of 7,000 victims.

- 31

The list of victims mentions his wife (59 years old). Yad Vashem/O.41/List of civilians killed in Kerch between November 16, 1941 and December 30, 1941.

- 32

However, the anthology film FILM DOCUMENTS OF THE ATROCITIES OF THE GERMAN FASCIST INVADERS (1945) shown at the Nuremberg trials indicates they were filmed on December 31, 1941, the day after the liberation.

- 33

Shneer, Grief, 44. His portrait was published in the Red Army’s illustrated newsreel WE TAKE REVENGE! and in a booklet entitled Atrocities of the German Fascists in Kerch: Evgeny. P. Stepanov, ed., Zverstva nemetskikh fashistov v Kerchi: sbornik rasskazov postradavshikh i ochevidtsev [German Nazi Atrocities in Kerch: A Collection of Stories by Victims and Eyewitnesses] (Suhumi: Abgiz Publishing, 1943), 105.

- 34

The victims’ nudity posed a problem for the reporters.

- 35

Where 800 Jews were kept in a ghetto before being murdered in December 1941. Megargee and Dean, Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, vol. 2, part B, 1757.

- 36

Film 16 is labelled as such: “These are the victims of traitor Tokarev. A 1.5 km pit filled with former citizens of Kerch who were shot to death.” https://www.vhh-mmsi.eu/mmsi/objects/48865/summary/media/9546.

- 37

Caption sheet without identifier, RGAKFD 6068-I, 3 ll.

- 38

On the caption sheet, 29-year-old Raissa, who survived the massacre, testified that she was there with her 5-year-old daughter Betia, her 2-year-old son Izia and her baby, who was born while they were in captivity. Her children died but her brother survived. Raissa is in the list of victims and so are Betia (aged 5), Iosif (18 months), Raisa Belotserkovskaia (4 days). Yad Vashem/O.41/List of civilians killed in Kerch between November 16, 1941 and December 30, 1941.

- 39

Caption sheet without identifiers, RGAKFD 6068-I, 5 ll.

- 40

Film script, RGAKFD 6068-I, 4 ll.

- 41

OTOMSTIM! KINODOKUMENTY O CHUDOVISHCHYKH ZLODEYANIYAKH I NASILIYAKH NEMETSKO-FASHISTSKIKH ZAKHVATCHIKOV. Shown by N. Karamzinskii. 1942. RGAKFD 4884. For analysis, see Hicks, First Films of the Holocaust, 60, 62, 64.

- 42

RGAKFD 6068 and RGAKFD 6067. Copies were made for Ukraine in 1961 and preserved at the TsGKFFA (H. S. Pshenychnyi Central State Cinema, Photo and Phono Archive of Ukraine) under record numbers 2033 and 2038. Evidence of the murder of Krymchaks in the Adzhimushkay anti-tank trench were not filmed during the second de-occupation (May 1944).

- 43

As per our calculation.

- 44

CM, f. 56, op. 1, d. 60-7, 57 ll.

- 45

CM, f. 56, op. 1, 63/16.

- 46

RGALI (Russian State Archive of Literature and Art), f. 2451, op. 1, d. 112, ll. 8–9 and d. 186, ll. 15–16. Quoted in Fomin, Tsena kadra, 378 and 384–386.

- 47

Even though this camp is known for the variety of its prisoners’ profiles and at the same time for its actual role in the Holocaust. Ruth Schwertfeger, A Nazi Camp Near Danzig: Perspectives on Shame and on the Holocaust from Stutthof (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022).

- 48

The cameraman shot 150 metres of film. Only 112 metres were preserved in the archives. In the remaining thirty-eight metres, whose location is now unknown, there was probably footage of the train carriage.

- 49

Caption sheet no. 1106, “Extermination camp Stutthof.” https://www.vhh-mmsi.eu/mmsi/objects/48907/summary/media/9588.

- 50

Caption sheet no. 1008, “Death Camp: Pan-European Factory of Human Extermination.”

- 51

Victor Barbat, “Kinooperator na voine: Marshruty poezdok Romana Karmena,” in Perezhit’ voinu: Kinoindustria v SSSR, 1939–1949, ed. Valérie Pozner, Irina Tcherneva and Vanessa Voisin (Moscow: Rosspen, 2018), 275–294.

- 52

Among the 480 detainees, the army found Soviet POWs and Polish farmers. But they also found several vehicles in Lublin that had been used to evacuate prisoners, including Jewish women and children, from the camp, which explains why the ex-prisoners who were filmed were mainly Soviets and Poles.

- 53

Analysed in Barbat, Roman Karmen, 321–326.

- 54

Filmed between June 20 and July 7, 1944, no identifier. Title: “Additional material to previous footage from the second series of films on the battle for our Soviet Ukraine.” The second episode of the filming session dealt with a killing in the Matronovskij monastery in Kholodnyj Yar.

- 55

Oleksandr Dovzhenko was trying to promote a change in narrative codes in the film industry. See Voisin, “De la paix à la guerre.”

- 56

GARF (Russian State Archives), Mark Troianovskij collection, f. 10094, op. 1, d. 92, l. 1.

- 57

GARF, f. 10094, op. 1, d. 92, l. 42.

- 58

Łoźna in Polish. The camp itself has not yet been identified.

- 59

Caption sheet no. 657, “People in a Concentration Camp.” The filmmaker wanted this footage to be included in the film THE LIBERATION OF BELARUS, and for certain survivors (Vitia Oganchenko, Pelageja Nebyvalova, I. Bogdanov, Valerij Kolesnikov and Dina Bogolidova) to be given particular prominence.

- 60

Quoted in Fomin, Tsena kadra, 808.

- 61

See the documents that were copied and included in the anthology Valeri Fomin, ed., Pobeda – navsegda! Kak sovetskie operatory snimali osvobozhdenie Evropy [Victory Forever! Soviet Cameramen Filming the Liberation of Europe] (Moscow: Kanon ROOI Reabilitatsiia, 2020), 26–31.

- 62

These words were spoken during a highly contentious meeting at the studio on August 28, 1944, quoted in Fomin, Pobeda, 40.

- 63

Fomin, Tsena kadra, 819.

- 64

Decree from the Party’s Central Committee, “On the Production of Newsreels and Film,” May 15, 1944, RGALI, f. 17, op. 117, d. 409, ll. 105–107. Quoted in Fomin, Pobeda, 31.

- 65

GARF, f. 10094, op. 1, d. 92, l. 35.

- 66

See Voisin, “Mark Troïanovski.”

- 67

He then became the studio’s deputy director.

- 68

Filmed on February 28, 1944, caption sheets nos 358 and 359.

- 69

RGALI, f. 2451, op. 1, d. 195, l. 6.

- 70

On the occupation and the Holocaust in this town in Ukraine’s Khmelnitskij region, see Megargee and Dean, Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, vol. 2, part B, 1369–1370.

- 71

RGALI, f. 2451, op. 1, d. 198, l. 7.

- 72

That was the case, for instance, with the footage by Ivan Panov and Konstantin Piskarev entitled “Death camp,” which showed a POW camp in the Olenino area. See review by Iouri Karavkin in May 1943, RGALI, f. 2451, op. 1, d. 130, l. 10.

- 73

This can be seen in the reviews quoted by Mark Troianovskij and Jurij Karavkin.

- 74

CM, f. 56, op. 1, d. 63-3.

- 75

The location’s name as listed by the cameramen does not correspond to any of the thirty-five Jewish camps in the Vinnytsia region, which was under the control of Germans. There were three German-managed camps in the area, where Jewish inmates were forced to build roads and bridges (Semensky and Bratslav). See Martin C. Dean, “Forced Labor Camps for Jews in Reichskommissariat Ukraine: The Exploitation of Jewish Labor within the Holocaust in the East,” East European Holocaust Studies 1, no. 1 (2023): 192.

- 76

Caption sheets nos 566, 567 and 568 indicate that the footage was earmarked for the “film archives of the Extraordinary State Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes.”

- 77

Caption sheet no. 1015. This footage was most likely filmed on July 25, 1944. The Zamość ghetto was created in April 1941 and liquidated in mid-October 1942. Deportations occurred throughout this period, including the deportation of 3,000 Jews to Bełżec in April 1942.

- 78

Ewa Koper, Włodzimierz Bonusiak and Jacek Chrobaczyński, “Rotunda–pierwsze upamiętnione miejsce martyrologii na Zamojszczyźnie,” Prace Historyczno-Archiwalne 30 (2021): 271–298. On the crimes committed in Zamość, see Christian Ingrao, Lapromessede l’Est: espérance nazie et génocide, 1939–1943 (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2016).

- 79

Review by Saakov and Nikolai Shpikovskij, editor-in-chief. April 28, 1944. RGALI, f. 2451, op. 1, d. 198, l. 14. See “Documents relating to the killing and deportation of the population of Skala,” USHMM/1995.A.0409. About 150 Jews from Skala survived the 1939–1945 period. Following the annexation by the Soviets in 1939, the population endured deportations and then occupations by first the Hungarian and later the German army. Jewish people were repeatedly sent to forced labour camps, and many were then murdered in the autumn of 1942. The branding of houses also dates from 1942. See the chapter on “Skala” in Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Poland, ed. Danuta Dąbrowska, Abraham Wein and Aharon Weiss, vol. 2 (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1980), 395–400, https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/pinkas_poland/pol2_00395.html.

- 80

The photograph is described on the website dedicated to the memory of the Jewish community in Skala Podilska: https://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/SkalaPodol/Stachel.html.

- 81

On the policy restricting access to the archives in Russia, see Sophie Coeuré, “Le siècle soviétique des archives,” Annales: Histoire, Sciences Sociales 74, nos. 3–4 (2019): 657–686; Sophie Cœuré and Florin Ţurcanu, “L’ouverture des archives des régimes communistes trente ans après: Les voies divergentes de la Roumanie et de la Russie,” Revue d’histoire moderne & contemporaine 69, no. 1 (2022): 71–87. These restrictions applied, for instance, to footage of Nazi crimes in Krasnodar, Nalchik and Georgievsk. GARF, f. 10094, op. 1, d. 92. The Nalchik footage mentioned in a telegram from Roman Katsman, deputy director of Glavkinokhronika, may have been partly used for newsreels and partly preserved in the archives. Voisin, “Footage of War Crimes,” 150.

- 82

This was specified by Vassil’chenko in December 1943. RGALI, f. 2451, op. 1, d. 186, ll. 15–16.

- 83

For example, Vladimir Sushchinskij filmed the exhumation of bodies for SMERSH (the counterintelligence service) in Melitopol in December 1943.

- 84

Such as the anthology FILM DOCUMENTS OF THE ATROCITIES OF THE GERMAN FASCIST INVADERS / KINODOKUMENTY O ZVERSTVAKH NEMETSKO-FASHISTSKIKH ZAKHVATCHIKOV, Central Studio for Documentary Film, 1945, edited by Elizaveta Svilova, directed by Roman Karmen.

- 85

Some were also intended for their peers. Roman Katsman wrote of the need for camermen to “start without delay to write diaries, preserve documents, letters, photographs, etc.“ This was in response to a suggestion from Grigori Boltianski that he write a book on documentary films during wartime. RGALI, f. 2057, op. 1, d. 188, l. 1.

- 86

Caption sheet dated February 15, 1943. Number assigned by studio: 2846.

- 87

Caption sheet no. 922, Orel.

- 88

Aleksandr Elbert in Dorogobuzh, caption sheet no. 1117, August or September 1943.

- 89

In the Simferopol region, cameraman Ivan Zaporozhskij clarified that he would keep filming “exhumations and investigations” but that “given the heat, it [was] impossible to show the number of bodies. They [were] buried immediately overnight.” Caption sheet no. 471, April 21–23, 1944.

- 90

Caption sheet nos 1138 and 1054, Kharkiv.

- 91

For example, the footage of the village of Homutovka and the city of Rylsk, occupied by the Wehrmacht, caption sheet no. 1109, “The Slave Camp”; or footage from Nizhnedneprovsk (Dnipro region), caption sheet no. 1299, September 27–28, 1943.

- 92

Solomon Kogan and Andrei Sologubov carried out two filming sessions on September 13, 1943.

- 93

In Shostka, a Ukrainian town occupied by the Wehrmacht. Caption sheet no. 1178, September 11, 1943.

- 94

This Czechoslovakian city was returned to Hungary in 1938. Its Jewish population was detained in two ghettos and almost entirely deported to Auschwitz in May 1944. See in particular Pavlo Khudish, “Ghettoization and the Holocaust in Transcarpathia in Testimonies of Victims and Witnesses,” Scientific Herald of Uzhhorod University. Series: History (2020), 90–101. See also the list of survivors from Uzhgorod in 1945: Yad Vashem file no. 572, https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/documents/6434815.

- 95

Caption sheet, “Fights for Uzhhorod and in Uzhhorod,” 420 m, unknown date and identifiers.

- 96

Timothy Snider, “The Life and Death of Western Volhynian Jewry, 1921–1945,” in The Shoah in Ukraine: History, Testimony, Memorialization, ed. Ray Brandon and Wendy Lower (Bloomington: Indiana University Press and USHMM, 2008), 77–113. The perpetrators who liquidated the Kolky ghetto in July 1942 were members of the Lutsk Security Police (SD), the German military police (Gendarmerie) and local Ukrainian police. Megargee and Dean, Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, vol. 2, part B, 1384 and on Maniewicze (Manevichi) 1419.

- 97

RGALI, f. 2451, op. 1, d. 198, l. 4, March 24, 1944.

- 98

Caption sheet no. 1044, “Traitor,” undated.

- 99

On the filming sessions for the kinoletopis’, see RGALI, f. 2451, op. 1, d. 186, ll. 15–16.

- 100

Jews who lived in the area under German control were murdered as early as autumn 1939. After Germany occupied the entire city on June 28, 1941, the ghetto was created. Its inhabitants were deported in several phases and exterminated in Bełżec. See Megargee and Dean, Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, vol. 2, part A, 555–558.

- 101

Anselm Bogorov, Vremia, zapechatlennoe kinoob’ektivom [Notes from a Documentary Filmmaker. Time Enshrined by the Camera’s Lense] (Leningrad: Lenizdat, 1973), 228.

Barbat, Victor. Roman Karmen, la vulgate soviétique de l’histoire. Stratégies et modes opératoires d’un documentariste au XXème siècle. PhD dissertation. Paris: l’Université Paris 1. 2017.

Bernard-Nouraud, Paul, Luba Jurgenson, and Irina Tcherneva, ed. Photographier la violence extrême: Témoigner par l’image. Paris: Petra, 2024.

Bogorov, Anselm. Notes from a Documentary Filmmaker. Time Enshrined by the Camera’s Lense [Zapiski kinokhronikera. Vremia, zapechatlennoe kinoob’ektivom]. Leningrad: Lenizdat, 1973.

Bruttmann, Tal, Stefan Hördler, and Christoph Kretzmüller. Un album d’Auschwitz. Comment les nazis ont photographié leurs crimes. Paris: Seuil, 2023.

Coeuré, Sophie. “Le siècle soviétique des archives.” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 74, nos. 3–4 (2019): 657–686.

Cœuré Sophie, Ţurcanu Florin. “L’ouverture des archives des régimes communistes trente ans après. Les voies divergentes de la Roumanie et de la Russie.” Revue d’histoire moderne & contemporaine 69, no. 1 (2022): 71–87.

Dean, Martin. “Forced Labor Camps for Jews in Reichskommissariat Ukraine: The Exploitation of Jewish Labor within the Holocaust in the East.” East European Holocaust Studies 1, no. 1 (2023). DOI: 10.1515/eehs-2022-0002.

Deriabin, Aleksei. Sozdateli frontovoi kinoletopisi. Biofil'mograficheskij spravochnik [The Creators of Film Annals at the Front. Biographical and Filmographic Catalog]. Moscow: Gosfilmofond, 2016.

Drubek-Meyer, Natascha. Filme über Vernichtung und Befreiung: Die Rhetorik der Filmdokumente aus Majdanek 1944–1945. Wiesbaden: Springer, 2020.

Fomin, Valeri, ed. The Cost of Framing the Scene: Soviet Filmed Chronicles of the War, 1941–1944 [Tsena kadra: sovetskaja frontovaja kinokhronika. 1941–1945]. Moscow: Kanon+, 2010.

Fomin, Valeri, ed. “Cry but keep filming!” Soviet Documentaries from the Front 1941–1945 [«Plach’te, no snimaite!» Sovetskaia frontovaia kinohronika 1941–1945 gg.] Moscow: Gosfilmofond, 2018.

Hakehillot, Pinkas. Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Poland. Volume II. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1986.

Hicks, Jeremy. First Films of the Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 1938–1946. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012.

Ingrao, Christian. La promesse de l’Est: espérance nazie et génocide, 1939–1943. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2016.

Koper, Ewa, Włodzimier Bonusiak, and Jacek Chrobaczyński. “Rotunda–pierwsze upamiętnione miejsce martyrologii na Zamojszczyźnie.” Prace Historyczno-Archiwalne 30 (2021): 271–298.

Khudish, Pavlo. “Ghettoization and the Holocaust in Transcarpathia in Testimonies of Victims and Witnesses.” Scientific Herald of Uzhhorod University Series: History (2020): 90–101.

Liebman, Stuart. “Documenting the Liberation of the Camps: The Case of Aleksander Ford’s Vernichtunglager Majdanek – Cmentarzyko Europy (1944).” In Lessons and Legacies. Vol. 7. Ed. Dagmar Herzog, 333–341. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2006.

Lindeperg, Sylvie. Nuremberg. La Bataille des Images. Paris: Payot, 2021.

Megargee, Geoffrey P., and Martin Dean, ed. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945, Volume II: Ghettos In German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Washington: USHMM, 2012.

Moine, Nathalie. Les vivants et les morts. Genèse, histoire et héritages de la documentation soviétiques des crimes. Paris: CNRS, (forthcoming).

Murav, Henriette, and Georgy Eistraikh. Soviet Jews in World War II: Fighting, Witnessing, Remembering. Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2014.

Pozner, Valérie, Alexandre Sumpf, and Vanessa Voisin, eds. Filmer la guerre: les Soviétiques face à la Shoah, 1941–1946. Paris: Mémorial de la Shoah, 2015.

Pozner, Valérie, Alexandre Sumpf, Vanessa Voisin. “Que faire des images soviétiques de la Shoah ?” Revue d‘histoire du cinema 1895, no. 76 (2015): 8–41.

Pozner, Valérie, Irina Tcherneva, and Vanessa Voisin, ed. Perezhit’ voinu. Kinoindustria v SSSR, 1939–1949. Moscow: ROSSPEN, 2018.

Schwertfeger, Ruth. A Nazi Camp Near Danzig: Perspectives on Shame and on the Holocaust from Stutthof. London, NY, Dublin: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022.

Voisin, Vanessa. “De la paix à la guerre, de la fiction au documentaire: Alexandre Dovjenko et Youlia Solntseva.” Conserveries Mémorielles, special issue The Cinema Goes to War: Screens and Propaganda in the USSR (1939–1949), ed. Valérie Pozner and Irina Tcherneva, 24 (2020). https://journals.openedition.org/cm/4549.

![“Soviet filmmakers in Auschwitz before the shooting” [Kenan Kutub-Zade and Mihail Oshurkov] January–February 1945. Photographer: V. P. Judin.](/sites/default/files/styles/9col/public/2024-12/Bildschirmfoto%202024-12-13%20um%2012.06.08.png?itok=D08PyQuQ)