Issue 2: Research, Debates and Projects 2.0

Recent political and historical events are increasingly interpreted through the lens of audiovisual media. The same goes for the production of historical memory. Media communicates, and at times even creates, historical knowledge, while film shapes our notions and understandings of history. Film furthermore not only showcases historical themes and sheds light on the biographies of historical figures, but also conveys historical understanding and consensus in audiovisual form. In this way, film shapes our images of the world and influences our perceptions. It also increasingly competes with and supplements established historiography. Documentaries, feature films, and home movies narrate history in aesthetically distinct ways and according to their own established traditions and modalities, while TV shows and online platforms make concessions to ratings and the business interests of big tech companies.

The second issue of the journal Research in Film and History explores current research, debates, and projects at the intersection between the disciplines of film studies and history. The articles are based on the research by a group of leading international scholars who presented and discussed their recent theories and projects at the Research in Film and History conference in Bremen in November 2018. The conference affirmed that the debates addressed in Issue 1: The Long Path to Audio-Visual History remain highly relevant to current research at the intersection between film and history. Issue 2 follows seamlessly on from issue 1, and can in many ways be seen as a version 2.0.

The issue is divided into three sections. Each section includes articles dealing with historical developments that began in the first half of the twentieth century as well as articles investigating phenomena from the very recent past. The aim is to create a dynamic interplay that not only allows theoretical and associative interconnections, but also enables a deeper understanding of the relevant methodology.

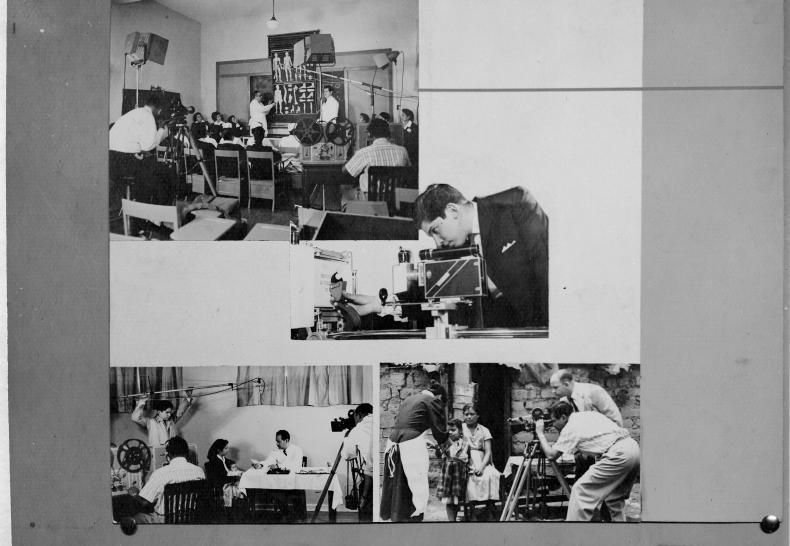

The first three articles focus on innovative studies of the presence and potential of film archives and archival material. In her article “Liberated on Film: Images and Narratives of Camp Liberation in Historical Footage and Feature Films,” Ulrike Weckel explores the difficult conditions in which Allied soldiers produced nonfiction films in the liberated Nazi concentration camps at the end of the Second World War. At the center of this investigation is the question of whether Allied cameramen and filmmakers, aware of how limited their understanding was, still tried to tell stories of liberation on film and, if so, what these stories were. By way of comparison, the article also discusses feature films that include scenes of camp liberation. María Rosa Gudiño Cejudo’s article “Mexican Public Health History through Film: The Riches of a Film Archive, 1945–1970” also looks at historical developments in the postwar period. She combines reflections on the use of film as a source in historical research on medicine and public health in Mexico with an analysis of qualitative aspects of the archiving process, examining how this film material has been disseminated and how some of these films have been made available on the archive’s website. The third essay, “Reel Life: Memory and Gender in Soviet Estonian Home Movies and Amateur Films. A Case Study of the Estonian TV series 8 MM LIFE (2014–2015),” expands the concept of archives to include collections of home movies and amateur films taken in the late 1980s. Based on a case study of the Estonian TV documentary series 8 MM LIFE [8 MM ELU] (2014–2015), Liis Jõhvik explores how the era of late socialism in Estonia is reconstructed and remembered in 8 MM LIFE through the illusion of watching home movies together. This article serves as a bridge to the second section, in which film is analyzed as a part of social history. As in the previous section, the first article looks at historical processes in the first half of the twentieth century; in this case, the growing awareness of the potential of film as a medium of mass communication. Christine Rüffert’s article “Film as Instrument of Social Enquiry: The British Documentary Film Movement of the 1930s” analyzes the documentary HOUSING PROBLEMS (UK 1935), whose ambiguous character is indicative of the tension between the filmmakers’ claim to be encouraging the self-confidence of the working class and their being representatives of government and industry interests. The second article, by Sebastian Köthe, looks at a more recent example of this complex interplay between representation and exploitation, specifically the relation between visibility and violence. Entitled “Visibility and Torture: On

the Appropriation of Surveillance Footage in YOU DON’T LIKE THE TRUTH,” it examines the first and only film to show surveillance camera footage from an interrogation in Guantánamo. Working from the idea that one aim of the violence practiced in the American POW camp at Guantánamo Bay is to make human beings excessively visible, Köthe asks how critical film research, which usually involves enhancing visibility, can avoid reproducing violence. This investigation of audiovisual material that is simultaneously an act of violence and a novel form of historical source leads us to the third section of issue 2, which comprises two articles on the audiovisual transformation of memory. Thomas Elsaesser’s article “Trapped in Amber: The New Materialities of Memory” traces the impact that moving pictures have had on history and memory. Elsaesser situates historical meaning-making in the interplay of obsolescence and nostalgia, document and proof, testimony and traumatic forgetting. A similar argument is advanced in Marian Petraitis’s analysis of mass participation documentaries, which rely heavily on participation and collaboration by large numbers of internet users. His article “Be Part of History: Documentary Film and Mass Participation in the Age of YouTube” takes a closer look at how these mass observations shape historical conceptions and asks to what extent they can serve as useful historical documents.

Issue 2 combines specific case studies with broader theoretical reflections. The aim is not simply to construct an internally consistent, self-contained collection, but to link up with and add fresh perspectives to discourses central to recent and future research at the intersection between film and history.

Rasmus Greiner

Bremen, November 25, 2019

Suggested Citation: Greiner, Rasmus: Issue 2: Research, Debates and Projects 2.0. Editorial. In: Research in Film and History. Research, Debates and Projects 2.0 (2019), No. 2, pp. 1–3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14803.