Mapping and Grounding Visual History

Methodological Reflections on Historical Research and Amateur Films

Table of Contents

Mapping and Grounding Visual History

Nonfictional Film as Historical Source

Benjamin and Deleuze

Film and History: Towards a General Ontology

Analyzing the Familiar

Migrations of Media Aesthetics

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Stein, Hanna: Mapping and Grounding Visual History: Methodological Reflections on Historical Research and Amateur Films. In: Research in Film and History. Sources – Meaning – Experience (2021-01-28), No. 3, pp. 1–22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/15451.

The pictorial turn has opened up the historical scholarship to visual sources and their potential use as research material, with “visual history” now encompassing a vast range of sources, methods, and approaches. Moreover, the decentering of history1 has multiplied perspectives, increased the attention given to microhistorical processes, and meant that more diverse genres of visual material now attract interest from researchers. With regard to film, there are now also studies of nonprofessional, noncommercial film genres and production modes. That includes research on amateur films, which “in all [their] shapes, sizes and genres”2 challenge the long-dominant tendency of historiography to disregard their scholarly significance and stigmatize them as ego-documents and hobbies that possess a merely personal relevance. A growing number of insightful studies on amateur films have finally begun to shed light on this part of film history.3 A methodological challenge that many of these endeavors face is how to simultaneously address both the visual material itself and its context, rather than giving undue emphasis to just one of the two. This remains a difficulty for historians who work with visual sources, and leaves them vulnerable to criticism. However, postmodern theories in particular have opened up space for methodological reflections and the development of new approaches.

In this article, I respond to the challenge by introducing a methodological combination of posttheoretical, neoformalist film analysis and postmodern situational analysis. While this approach may seem contradictory, it offers fruitful possibilities for scholars to work from within a film while also grounding it within a larger situation. Both strands stimulate and focus on the process of theorizing and grounding knowledge production in the material itself, allowing us to avoid predetermined (theoretical) assumptions and reconsider a film’s specific characteristics, and offering new points of departure for historical film research. After an introduction explaining the choice of methods, I turn to Yugoslav amateur films, focusing in particular on the film ŽEMSKO/GAL (Dunja Ivanišević, Yugoslavia 1968), as a source for representations and discourses of the everyday. While the methods presented here can be applied to any kind of film genre, they are especially helpful for analyzing the amateur films produced collectively in “ciné clubs.” Treating them as historical sources (in an expansive sense of the concept) requires us to understand the films in terms of the way they were produced — namely, as Ryan Shand puts it, in a “community mode”4 — and as products of situations in which human and nonhuman actors, discourses, artistic regimes, and sociopolitical conditions come into play. By exploring the entire situation in which the productions are embedded, I reinforce amateur films’ status as microhistorical documents and integral components of a larger cultural and filmic landscape.

Applying the microhistorical approach to filmic representations of the everyday follows from amateur film’s production conditions. Films in general, but especially amateur films, lend themselves as subjects for microhistories, Alltagsgeschichten, and histories from below for various reasons. Firstly, they are able to reveal hidden actors, unrepresented people, and silenced discourses within larger narratives, thus uncovering the homogenizing ways of writing and perceiving history.5 This not only enhances our understanding of sources and subjects, but also our knowledge of, and perspectives from within, a variety of film genres.6 Secondly, film analysis requires a researcher to be close to the subject, which, in contrast to a distanced, macrohistorical perspective, forces and enables a condensed and focused analysis of details.7 Such “close-ups,” as Kracauer describes microhistorical perspectives, allow us to attain a more realistic — though nonetheless narrated — history, which never remains stuck at the level of fine detail but extends into larger dimensions.8 According to Kracauer, films as close-ups enable the spectator (and researcher) to see and experience a relation to materiality, a world “which has never been seen before, a world which escapes the gaze as does Poe’s stolen letter that is untraceable because it is in reach of everyone”.9 Thus, microhistorical perspectives and amateur films as microhistorical documents bring us closer to the ubiquitous, unseen, invisible, and unexperienced, and offer a detailed understanding of social and cultural history. Last but not least, “in the micro dimension a more or less dense fabric of given data canalizes the historian’s imagination, his interpretative designs”.10 In Kracauer’s definitions of microhistorical dimensions and film as materiality, the researcher figures as an active participant, driven by experiences and perceptions11 — an aspect that will play a central role in my subsequent methodological reflections. Having recognized these opportunities that are offered to us by amateur films as microhistorical documents, we are left with the question of how to methodologically ground them so that films and researchers can tell stories of the everyday.

Nomadic Objects and Researchers

In Explorations on Post-Theory, Fernando de Toro writes, “Something has happened. In the last two decades … we have witnessed the emergence of the Post”.12 “The Post” has brought about a decentering of knowledge and knowledge production; the end of universalizing theories; increasingly blurry disciplinary boundaries; and “the simultaneous elaboration of theory from conflicting epistemologies”.13 Lifting up voices from the margins — subaltern, colonized, female* subjects — have problematized the distinctively modern assumptions underpinning the sciences and empowered the “end of centres”.14

This development has had wide-ranging effects on historical film research. I shall highlight two main examples in order to explain my proposed methods. Firstly, there has been a transformation of how the object of study is conceived. While under modern conditions this object was perceived as specific to a particular discipline and as a stable observable entity, it is “now […] nomadic, cartographic, rhizomatic. […] here and there at the same time”.15 Applying the idea of films as nomadic objects, i.e. as crossing disciplinary boundaries as well as their own generic limitations, allows us to overcome the aforementioned dichotomy, which has created a stalemate in historical film research between the “evidential mode”16 that leaves aside the context and a contextualization that tends to forget the film itself.17 The widened understandings of films as open systems,18 as products of practice, spectatorships, power, and knowledge, as conditions for and conditioned by technology, sociocultural relations, and individual and mass emotions,19 and as myth-motors20 have already helped researchers to move beyond the separation of film and context. However, highlighting the nomadism of film could further advance the dissolution of its hermetical demarcations, by understanding the moving picture as drifting between the different (temporal, spatial, symbolic, social) systems of meaning. Therefore, methods are needed to grasp and analyze film “on the move.” Instead of asking how to read films,21 the question should be why we do not watch, map, disassemble, dig into, or strive through the network of a film, and why we do not take a closer look at how films move us, as well as history and discourses — thereby allowing us to understand and theorize them.

The nomadism of “the Post” also concerns the researcher as a situated nomadic subject.22 These characteristics may seem contradictory — static (situated) vs. on the move (nomadic) — but they form an interplay in postmodern subjectivity, which is determined by its conditions of being (that is: the intersectional condition of gender, class, race, and age) and moving (that is: migration, striving through texts/films, crossing disciplinary lines). As feminist and postcolonial epistemologies have pointed out, there is no unmarked position for the researcher to occupy, but only highly involved subjects simultaneously seeking and producing knowledge. This awareness of one’s own positionality, and the narrativity dependent on it, does not imply the end of all narrative, theory, or knowledge, but rather a diffusion and multiplication of, and (self-)reflection on, knowledge production and the power structures involved in it. Moreover, acknowledging our involvement is essential to overcome skepticism of affect, and increases our ways of understanding (films). Instead of shying away from studying films because of our emotional involvement with them, this involvement should instead be embedded into the research process and acknowledged as a strength for knowledge production.

Situational Analysis, Neoformalism, and Amateur Film

How should historians approach amateur films that were made in ciné clubs, which result from a collective mode of production influenced by many different factors, such as the club’s discourses, professional cinema, cultural politics, artistic regimes, mainstream culture, and so forth? How can they stay focused on the visual material when there are so many contextual aspects to be considered? How can I situate myself as a researcher within the field? The point of methodological departure is contradictory. While situational analysis enables us to capture the research situation, the neoformalist approach brings the visual into focus in order to deduce information about the film and the situation — so that a back and forth between them offers an enhanced and embedded understanding of the visual and its historical and contemporary conditions.

Situational analysis, as developed by Adele Clarke, is a postmodern version of grounded theory, a “theory/methods package” that takes into account the “social ecology/situation — grounding the analysis deeply and explicitly in the broader situation of inquiry of the research project.”23 For (amateur) film analysis, it has five specific strengths. Firstly, the expanded understanding of the research field as a situation, i.e. a dimension that accumulates interplaying and counteracting human and nonhuman actors and actants, discourses, and processes. The context is not treated here as a further entity that accompanies the film and has to be analyzed separately; rather, the context is the situation, and the film is one of the many elements within it. Secondly, the social-interactionist approach and inclusion of social worlds/arenas theory widens our understanding of social practices as a relationality of collective actors, i.e. social worlds that actively help to shape “universes of discourse”.24 The multiplicity of social worlds (e.g. the earlier-mentioned different participants within ciné club amateurism) can create conflictual situations whose analysis enables us “to see power in action”.25 This requires a special attention to the involved actors and actants, which can be physically present in situations yet have unequal power and be discursively constructed or silenced. Thirdly, the posthumanist ideas underpinning situational analysis introduce a salient consideration of nonhuman actors with their own agencies, allowing us to comprehensively capture all elements of a situation. Films are thereby defined and analyzed as active and influential participants within discourses. Fourthly, the method of mapping26 helps us “to understand, make known, and represent the heterogeneity of positions taken in the situation under study” without “performing recursive classifications that ignore the empirical world”.27 Moreover, this method for collecting and analyzing data involves the researcher directly in the situation, lays open the process of research; to create, change, multiply, dive into, strive through maps in order to build knowledge from the captured material is to nomadically move along the object of study. Fifthly, the postmodern, decentralized definition of a situational matrix (i.e. context) expands and multiplies the meaning of context. One could argue that introducing “situation” as the object of research is simply replacing “context” by yet another term, and thus reconstructing the film/context dichotomy. However, there is a difference that can be better understood by taking into account the matrix of the research field, which was defined as “conditional” in traditional grounded theory and as “situational” by Adele Clarke. The difference is the basic structure of the object’s position in the field. Grounded theory defines the object of interest as the center and successively builds centrifugal, causal frames of influential aspects around it, so that the field is structured by a hierarchical construction of significance. By contrast, the situational matrix describes a decentralized network, a map of all the aforementioned aspects of the situation that are not chosen and codified in hierarchical order but accumulated and interpreted in all their relations — enabling us to identify movements, dependencies, clusters, and agencies.28

David Bordwell harshly criticizes postmodern approaches as one “large scale trends of thought”29 in the field of film studies, which tend to “simply restat[e] the humanist’s uninformative truism that everything is connected to everything else.”30 Nevertheless, I suggest introducing his posttheoretical, neoformalist approach into situational analysis — that is, specifically, at the point where the mapped films are considered in fine-grained detail. Bordwell argues for a re-strengthening and understanding of films as artworks,31 which can be theorized by neoformalist analysis. As Ryan Shand argues in his study on Scottish amateur films, the neglect of the formalist idea of films in more recent studies has caused two problems. On the one hand, it has led to research on films not being based on empirical evidence, and on the other hand it refuses to recognize new possibilities and developments that have arisen within formalist scholarship.32 One of these possibilities is the neoformalist approach of “historical poetics” described by Bordwell, which starts with a close “reading” of the film and continues by deducing ideas of the “artistic intentions, craft guidelines, institutional constraints, peer norms, social influences, and cross-cultural regularities and disparities of human conduct.”33 This is crucial when it comes to the analysis of amateur films produced in the community mode of clubs, since these films often are expressions the clubs’ artistic regimes, the wider network of the (amateur) film scene, and mainstream cultural trends.34 The neoformalist reading of historical poetics is based on the assumption of films as formal systems from which one can start theorizing, and thus adds a necessary empirical and evidential approach to the postmodern theory. This creates two opportunities: The conscious inclusion of the researcher’s interpretation of the film, which is needed to make statements about authorial intention,35 and the deduction of knowledge from the film’s formal criteria, which in turn can be fed into the situation and inform us about the agency of the visual material itself.

Both approaches are based on the idea of theorizing from research material: one grounding it within large, situational matrixes, the other within the formal system of the film. Both individually offer great potential for historical studies of film, but taken together they might be able to push it even further, accounting for films’ status as active objects within their situation and as formal systems, embodying artistic principles and authorial intentions whose decoding helps us to build knowledge about the films and their situation. We see here not only the possibilities that arise if researchers establish new modes of affective knowledge production, but also the constant movement for which I argue: the movement between the visual, its systems, and our own positions. Thus, mapping and analyzing turns into moving between the big picture — the situation — and the smaller picture — the film — and hence allows us to build interconnected knowledge from both.

One Example: The Feminist Agency of a Film on the Move

The example I shall give to show how these methodological considerations can be applied is only one part of a situational analysis intended to provide a theoretical account of discourses of the everyday in Yugoslav amateur films. The film industry and film culture were of key interest for the newly established political system in Yugoslavia after the devastating Second World War. Movies were important means of political legitimization, while the film industry was a major economic factor, and film culture in its technological terms was a effective means for educating the people. With this latter aim in mind, the Communist Party (later — League of Communists of Yugoslavia) set up amateur film clubs all over the republic, which generated a network of film amateurism, linked together by yearly film festivals, cooperation, exchanges, and publications. As (an albeit marginal) part of an emerging Yugoslav film culture, an active and influential amateur film movement developed throughout the 1960s and paved the way for new film and art tendencies such as “Novi/Crni Talas” and “Anti-Film”.36 Thus, an entire cluster of Yugoslav amateur film needs to be taken into account as a social practice, as a political institution, and as cultural production. It was supplemented by political developments, such as far-reaching liberalization, economic growth, and the anchoring principle of self-management, which influenced discourses in society and (popular) culture. For many, if not most, Yugoslav amateur films it is possible to identify and map manifold arenas in which the films participate. There are films about tourism, transport, and urban or rural life, feature films, experimental rhythmic camera movements, anti-films, and much more.

However, as noted earlier, the strength of mapping the films’ discourses is that it allows us to shed light on topics that are either entirely absent or only present implicitly. From a feminist standpoint, we will almost immediately observe that this applies to gender relations and the position of women* in the relevant situation. Watching numerous amateur films made me a spectator to women* being represented in many different yet similar ways: They are implicitly constructed by male filmmakers, and are almost always represented in an objectified, sexualized way. Moreover, much less is known about women’s participation in amateur film clubs, because not only were they one of the silenced social worlds within the male-dominated practices and discourses of the situation, they were also neglected by a historiography that did not consider female participation in amateur scenes. Nonetheless, there were female members37 in amateur film clubs, whose films only recently became publicly known thanks to the efforts of archivists and researchers. Thus, it is possible to focus on their (filmic) participation in discourses and representations of femininity.

Let us take a closer look at one filmmaker and her film, which on the one hand adds a new position to this arena, and on the other hand sheds light on the agency of nonhuman actors, including the film itself. Moreover, it reveals the nomadic object of research at work. In the early 1960s, Dunja Ivanišević was a member of Kino klub Split (well-known for former members like Lordan Zafranović and Ivan Martinac and as a place of specific experimental films), who made one film: ŽEMSKO. The film’s fate shows how unconventional positions were actively silenced, but at the same time its rediscovery enables us to trace back the positions of power and the filmmaker’s filmic position. As Ivanišević stated in an interview,38 the film was supposed to be submitted along with other Kino klub Split productions to an experimental film festival in Pančevo the same year, but someone “forgot” to send it. The film and Ivanišević’s filmmaking activity were likewise forgotten when she quit the club soon after this incident. Thanks to Zafranović, the film was saved from oblivion, and the gauge was dug out from the club’s archives for its first public screening at the 1987 Assembly of Alternative Films in Split.

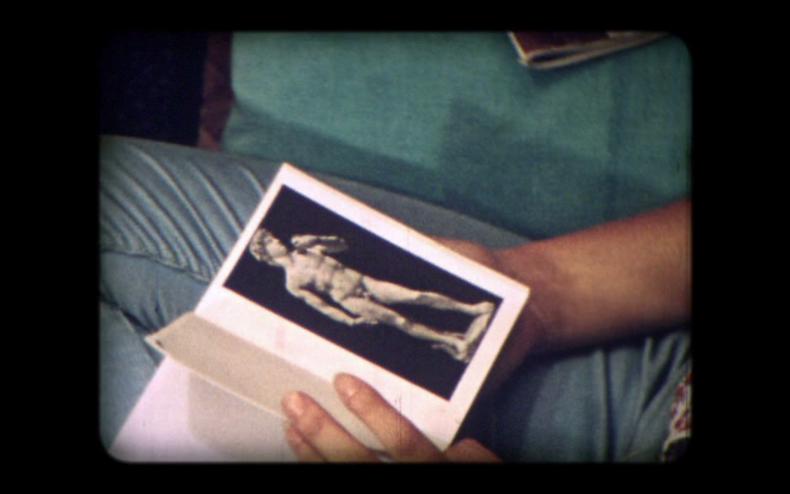

ŽEMSKO is an eight-minute-long portrait of a young woman,39 beginning with a depiction of a biblical painting of Eve physically emerging from Adam’s body. The remainder is divided into three parts, which appear to address the question of female subjectivity. In the first part, the young girl is confronted with different gender representations and social expectations. She dances in front of and around a John Lennon poster, occasionally kissing and looking longingly at it. She sits on a couch, flicking through the lifestyle magazine Grazie, filled with adverts for wedding dresses, and through a book about Michelangelo’s sculptures, with a long close-up on the page showing the sculpture of David — the idealized naked male body, the biblical hero. The girl’s cautious behavior and dancing are intercut with images of adverts portraying stereotypes of femininity and female politicians and pop culture icons. Hence, her dance throughout the first half of the film is a movement through imposed representations of gender norms, role models, and idols. This perception is reinforced by the accompanying song, Ben E. King’s Stand by Me. The construction of femininity in relation to someone else is underscored by the song’s repetitive call for the “darling [to] stand by me, stand by me […]” — a call for the unconditional love and support of a woman towards a man.

In an intercut between the first and second part of the film, the woman who danced through the medially imposed norms now lies still, covered with a white blanket, her hair spread around her head. While King continues to sing Stand by Me, she appears to be lying dead, motionless, eyes open, staring at an unknown point. The composition creates the picture of a Medusa — the mythical figure who turns anyone who beholds her to stone — and makes the sequence into a thirty-second-long catharsis, at the end of which the gal turns out to be different.

The postcathartic part of the film begins with the girl putting a record on the gramophone. This time, she chooses her own song, Wilson Pickett’s Funky Broadway, to which she starts dancing more freely than before. The camera mostly captures her in shaky close-ups, which do not really allow us to see her but rather the rhythmic movements of her head, hands, hair, and body. While the first part was dominated by representations of other women and men, now there are only brief moments in which the spectator can catch a glimpse of the Lennon poster somewhere in the background — a blurry, always smiling observer. The focus is on the woman herself — not as a picture but as an accumulation of different poses, movements, and emotional expressions.

The conclusions we can draw from this brief description of the film seem clear, almost unavoidable: There is a progress from a girl’s identity, formed by male and female role models and social expectations, towards a self-assured, independent woman. The cathartic intercut of the Medusa figure, who appears almost dead after the first half of the film, creates a clear break between these states of being, and the music underlines this impression. When Pickett sings, “Out on Broadway, there’s a woman; name of the woman Broadway woman,” the spectator understands that the woman is no longer an infantilized “darling” who is supposed to stand by her man as she was in the first song. At the very end of the film, the camera shifts from the inside of the apartment towards a narrow street, shot from above. The sound of Freaky Broadway reaches out to the public space where people are walking by, while the camera moves upwards — towards the blue sky, opening up an even bigger space.

In terms of its style and elements, ŽEMSKO can be identified as strongly embedded in the artistic regime of the Kino klub Split, whose distinctive style is characterized by experimental, rhythmic films, jump cuts, and poetic visualizations of everyday surroundings.40 But with its storyline and theme, ŽEMSKO goes beyond the club’s specific trends and practices of filmic exploration by shifting the focus from the urban and rural environments towards the female individual in a private space, though one that is nevertheless influenced by its social and cultural environment. This analysis of the film’s formal systems leads us back into the situation not just because of its participation in a discursive arena but also because of its interdependency with wider film trends and styles. In the period when ŽEMSKO was made, there was a general shift towards the individual in Belgrade’s amateur clubs, as well as on the big screens of Yugoslavia, where the main (ideological) themes of the People’s Liberation War, “brotherhood” and “unity,” had been replaced by a psychological realism focused on the individual, which allowed filmmakers to subtly voice criticism of the political system.41 But Ivanišević’s film is still distinctive because of its focus on a female protagonist, which could not be found on any other bigger or smaller screen.

Due to its formal and narrative aspects, the film is occasionally labeled the first feminist Yugoslav film.42 However, as Ivanišević states in the above-mentioned interview, she never saw herself as a feminist, but simply wanted to make a film about the development of a female subjectivity. This intention, or rather non-intention, on the part of the filmmaker opens up several different yet intertwined strands of analysis. Firstly, it raises the question about the presence of any feminist discourse in the analyzed period. If a person makes a film that, judged from today’s perspective, is a powerful feminist work, but without intending to do so and without regarding female subjectivity as a feminist topic, this might be attributable to an environment in which there was little or no space for feminist positions, since a strong feminist social world only began to emerge in Yugoslavia in 1978.43 Moreover, “women’s issues” were not specifically addressed in the society, since the prevailing presumption was that legal equality had made them obsolete. Hence, the director might not have known that the film she made takes a feminist position par excellence, while the fate of the film gauge itself suggests that other actors in the situation may perhaps have detected something threatening or inappropriate in it (the woman and/or the emphasis on the individual). Thus, a discursive arena of femininity and women’s* positions can be identified — an arena that did not yet have strong advocates, but was consciously and unconsciously silenced by contemporary social worlds. Secondly, a formalist analysis of the film against this backdrop brings the agency of the film into play: ŽEMSKO narrates the transformation of a woman’s subjectivity in a highly metaphoric and poetic way, adding to the (amateur) film scene and its productions a theme that was at that time underrepresented and treated only through a male-dominated lens. Its three-stage narrative — imposed identity, catharsis, liberation — puts the focus on the psychological development and liberation of a woman. This interpretation is reinforced by the music, which underlines the sequence’s content and the behavior of the woman in the first and final parts. Thirdly, the emphasis on the feminist aspects of the film is a result of its nomadism as a research object and of my own positionality. The way I analyze the film is based on my particular background, which for whatever reason leads me to view the film’s content in the way I have suggested, but is also attributable to the film’s being analyzed from different disciplinary perspectives, as well as to its having reemerged, after a long disappearance, into a completely different context with different cultural codes and figures. Fifty years ago, audiences might have watched and understood it differently than today — the object of research is not the same anymore, even though it presents us with the same content.

Conclusion

The combination of neoformalist film analysis and situational analysis appears to have opened up space for what Filippo de Vivo calls a “seriously microhistorical methodology, combining the magnifying lens with the radar in search of connections”.44 The analyzed film’s pictures, editing, and sound tell the story of a young woman’s development from a feminist perspective (or at least are interpreted that way). Moreover, the film reaches beyond the visual, building stylistic connections to the community of amateur filmmakers and textual references to the professional film trends of the early 1960s. The fate of the film gauge and the filmmaker herself signal the social conditions of making (amateur) films and the gendered dimension of research. The inclusion of the director’s intention and the film’s (re)appearance within differing historical and political contexts adds to the field of multiple relations yet another special dimension of the object’s agency. Thus, the analytical approach from different perspectives, the move between close-up and wider scope, enables us “to establish dynamic interconnections”45 and multilayered findings about widely unknown and underrepresented fields of research: amateur film club productions and the position of women within those productions. The seemingly small-scale history of Yugoslav amateur filmmakers does not remain small, but opens up a wide field of research into the everyday as cultural practice, discursive construction, and social relation.

When he proclaimed the pictorial turn and asked what pictures are or rather what they want, Mitchell stressed the necessity of dedisciplinary and indisciplinary practices. He differentiated these two ways of departing from the idea of a clearly defined discipline as, respectively, a deliberate, playful act “which recognizes a disciplinary frontier and determines, for some reason […,] to cross it” and a “more scary, vertiginous activity [that] arises when you’re lost”.46 What I have proposed, with my methodological reflections and brief illustration of how to apply them to amateur films, is at once a dedisciplinary and an indisciplinary endeavor, a conscious getting-lost — a nomadic movement from films to social worlds, to situations, a discourse back and forth, striving through the visual as a wide field of relations. Nevertheless, this getting-lost has a goal — a process of in-depth analysis and theorization by which historians can reinforce amateur films’ status as microhistorical documents, as medial agents, and as components of a situation that reaches beyond the gauge of the film, yet interferes in the film itself. ŽEMSKO is but one example of many that could have been given.

- 1For an introduction on effects of postmodernity on History, see Keith Jenkins, Re-Thinking History. London: Routledge, 1991. On decentering History from a postmodern and postcolonial perspective, see Natalie Davis, “Decentering History: Local Stories and Cultural Crossings in a Global World,” History and Theory 50, no. 2 (2011): 188–202.

- 2Bert Hogenkamp and Mieke Lauwers, “In Pursuit of Happiness? A Search for the Definition of Amateur Film,” in Jubilee Book/Association Européenne Inédits, ed. European Association Inédits (Charleroi: Association Européenne Inédits, 1997), 107.

- 3Some examples are studies on the interrelation of ideologies and identities in home movies (Roepke, “Crafting Life into Film”; Zimmermann, “Mining the Home Movie,” et. al.); of visual construction of ‘the Other’ and power relations in private travel films (Zimmermann, “Geographies of Desire”); of amateur war recordings which shed light on the deviating narratives from official reports (Boyle, “Amateur Film and the Researcher”). Ciné club amateurism is among others analyzed by Ryan Shand on the example of Scottish Amateur clubs (Shand, “Amateur Cinema: History, Theory, and Genre (1930–1980)” and by Greg DeCuir who focuses on the Yugoslav clubs (DeCuir, “Yugoslav Ciné-Enthusiasm”; “Early Yugoslav Ciné-Amateurism”).

- 4Ryan Shand, “Theorizing Amateur Cinema: Limitations and Possibilities,” The Moving Image 8, no. 2 (2008): 36–60.

- 5John Brewer, “Microhistory and the Histories of Everyday Life,” Cultural and Social History 7, no. 1 (2010): 87–109.

- 6The focus on Hollywood, professional feature filmmaking and National Cinemas increasingly decentered by shifting to transnational film productions, post-colonial cinema and the inclusion of genres such as documentary, animation and amateur film.

- 7István Szijártó, “Four Arguments for Microhistory,” Rethinking History 6, no. 2 (2002): 209–215.

- 8Siegfried Kracauer, History, the Last Things before the Last (New York: Oxford University Press, 1969), 122.

- 9The quote is the author’s translation of Siegfried Kracauer, “Erfahrung und ihr Material (1960),” in Texte zur Filmtheorie, ed. F.J. Albersmeier (Stuttgart: Reclam, 2003), 238.

- 10Kracauer, History, the Last Things before the Last, 123.

- 11Thomas Elsaesser discusses amateur films at the intersection of cultural memory, individual trauma, and historical topologies whereby he well illustrates the emotional involvement of the researcher (Elsaesser, “Trapped in Amber”).

- 12Fernando d. Toro, “Explorations on Post-Theory: New Times,” in Explorations on Post-Theory: Toward a Third Space, ed. Fernando d. Toro (Frankfurt am Main: Vervuert Verlagsgesellschaft, 1999), 9.

- 13Toro, “Explorations on Post-Theory”, 10.

- 14Jean-François Lyotard, The Post-Modern Condition (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984).

- 15Toro, “Explorations on Post-Theory,” 11.

- 16Shand, “Theorizing Amateur Cinema: Limitations and Possibilities”.

- 17Günter Riederer, “Film und Geschichtswissenschaft: Zum aktuellen Verhältnis einer schwierigen Beziehung,” in Visual History: Ein Studienbuch, ed. Gerhard Paul (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2006).

- 18Paul Kusters, “New Film History: Grundzüge einer neuen Filmgeschichtswissenschaft,” montage AV 5, no. 1 (1996): 49.

- 19Robert Sklar, “Moving Image Media in Culture and Society: Paradigms for Historical Interpretation,” in Image as Artifact: The Historical Analysis of Film and Television, ed. John. E. O'Connor (Malabar: Robert E. Krieger, 1990).

- 20Gerhard Paul, ed., Visual History (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2006), 24.

- 21Riederer, “Film und Geschichtswissenschaft.”

- 22See especially Haraway, “Situated Knowledges” and Braidotti “Nomadic Subjects.”

- 23Adele E. Clarke, “From Grounded Theory to Situational Analysis: What's New? Why? How?,” in Situational Analysis in Practice: Mapping Research with Grounded Theory, ed. Adele E. Clarke, Carrie Friese, and Rachel Washburn (Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 2015), 89.

- 24Clarke, “From Grounded Theory to Situational Analysis”, 86.

- 25Adele E. Clarke, Situational Analysis (London: SAGE, 2009).

- 26Adele Clarke introduces three maps which are never completely distinguishable and whose order can change in the process of research. The situational is to identify all the elements of the situation and their relations. The social world/arena map serves to capture the collective actors and arenas, moving from the individual to the sociability of the worlds — thus, finding place in-between modern individualism and postmodern fragmenting. The positional map helps to have the major positions of actors and social worlds laid out and to identify controversies within the situation (Clarke, Situational Analysis).

- 27Adele E. Clarke, Carrie Friese, and Rachel Washburn, eds., Situational Analysis in Practice (Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 2015), 138.

- 28For more details and illustrations of the different matrixes see Clarke, “From Grounded Theory to Situational Analysis.”

- 29David Bordwell and Noël Carroll, eds., Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996), 3.

- 30Bordwell and Carroll “Post-Theory,” 12.

- 31David Bordwell, Poetics of Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2008), 1.

- 32Shand, “Amateur Cinema,” 17f.

- 33Bordwell, Poetics of Cinema, 1.

- 34Shand, “Amateur Cinema.”

- 35Ryan Shand, “Introduction: Ambitions and Arguments – Exploring Amateur Cinema Through Fiction,” in Small-Gauge Storytelling: Discovering the Amateur Fiction Film, ed. Ryan Shand and Ian Craven (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013).

- 36On Yugoslav film industry see Goulding, “Liberated Cinema.” For the amateur film culture in Yugoslavia see DeCuir, “Yugoslav Ciné-Enthusiasm”. The mentioned developments steamed especially from Belgrade, where members of the club became active within the professional film culture and introduced critical political narratives. In Zagreb, a circle of film amateurs fostered film- and art theoretical discourses, questioning the role of the camera in the process of filmmaking and the materiality of the film itself.

- 37As Petra Belc argues, the rare attention paid to female filmmakers from the amateur scene is caused by the fact that they were less anchored in the Yugoslav art scene, so that Zagreb-based Tatjana Ivančić — an experimental film director and the first women who received the title ‘The Master of Amateur Film in Yugoslavia’, Bojana Vujanović in Belgrade, Divna Jovanović with hand-painted experimental films, Dunja Ivanišević from Split and many other tend to be forgotten when it comes to the history of Yugoslav amateur film and its achievements (Belc, “Yugoslav Experimental Cinema”).

- 38Antonela Marušić, “Dunja Ivanišević, Redateljica Prvog Domaćeg Feminističkog Filma ‘Žemsko’”, VoxFeminae.

- 39The actress is Iskra Kuzmanić who also played in other productions of the club in Split.

- 40Dijana Nenadić, “'Splitska Škola' između klupske i osobnih mitologija/'split School' Between club and personal mythology,” in Fradelić, Nenadić, Perojević, eds., Splitska škola filma/Split Film School: 60 godina Kino kluba Split/60 Years of Cine Club Split, 46.

- 41Daniel J. Goulding, Liberated Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002).

- 42See especially articles on film culture in the region: Marušić, “Dunja Ivanišević, Redateljica Prvog Domaćeg Feminističkog Filma ‘Žemsko’”; Višnja Vukašinović, “Žemsko – Njena četiri zida”; Dijana Nenadić, “Tatjana Ivanišević – Dunja (1942–2014). Odlazak prve „žemske“ hrvatskog eksperimentalnog filma.”

- 43In 1978, a first Yugoslav-wide gathering of feminists – Drug-ca Žena — took place in Belgrade and marks the beginning of a feminist movement.

- 44Filippo de Vivo, “Prospect or Refuge? Microhistory, History on the Large Scale,” Cultural and Social History 7, no. 3 (2010): 394.

- 45Brewer, “Microhistory and the Histories of Everyday Life”, 97.

- 46Christine Wiesenthal, Brad Bucknell, and William J. T. Mitchell, “Essays into the Imagetext: An Interview with W. J. T. Mitchell,” Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal 33, no. 2 (2000): 11.

Belc, Petra. “Yugoslav Experimental Cinema between Film and Art: Regional Heritage, Feminist Critique and the Question of Methodology.” In II. International Forum for Doctoral Candidates in East European Art History, Berlin, April 30, 2015, organized by the Chair of Art History of Eastern and East Central Europe, Humboldt University Berlin. http://www.kunstgeschichte.hu-berlin.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Belc….

Benčić, Branka. “Sve je Povezano/Everything is Connected.” In Splitska Škola Filma/Split Film School: 60 Godina Kino Kluba Split/60 Years of Cine Club Split. Edited by Sunčica Fradelić, 1–30. Split: Kino klub Split, 2012.

Bordwell, David. Poetics of Cinema. New York: Routledge, 2008.

Bordwell, David, and Noël Carroll, eds. Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996.

Boyle, Stephanie. “Amateur Film and the Researcher: Alternative Perspectives of Australian Soldiers in Vietnam.” Australian Academic & Research Libraries 40, no. 3 (2009): 223–233.

Brewer, John. “Microhistory and the Histories of Everyday Life.” Cultural and Social History 7, no 1 (2010): 87–109.

Braidotti, Rosi. Nomadic Subjects. Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011.

Clarke, Adele E. Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory after the Postmodern Turn. London: SAGE, 2009.

Clarke, Adele E., Carrie Friese, and Rachel Washburn, eds. Situational Analysis in Practice: Mapping Research with Grounded Theory. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 2015.

Cuevas, Efrén. “Change of Scale: Home Movies as Microhistory in Documentary Films.” In Amateur Filmmaking: The Home Movie, the Archive, the Web. Edited by Laura Rascaroli, Gwenda Young, and Barry Monahan, 139–151. London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2014.

Davis, Natalie. "Decentering History: Local Stories and Cultural Crossings In a Global World." History and Theory 50, no. 2 (2011): 188–202.

DeCuir, Greg. “Yugoslav Ciné-Enthusiasm. Ciné-Club Culture and the Institutionalization of Amateur Filmmaking in the Territory of Yugoslavia from 1924–1968.” Romanian Review of Political Sciences and International Relations 8, no. 2 (2011): 36–49.

DeCuir, Greg. “Early Yugoslav Ciné-Amateurism. Cinéphilia and the Institutionalization of Film Culture in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia during the Interwar Period.” In The Emergence of Film Culture. Knowledge Production, Institution Building, and the Fate of the Avant-garde in Europe, 1919–1945. Edited by Malte Hagener, 162–179. New York: Berghahn Books, 2014.

Elsaesser, Thomas. “Trapped in Amber: The New Materialities of Memory.” Research in Film and History, no. 2 (2019). DOI: https://doi.org/10.26881/pan.2018.19.10.

Elsaesser, Thomas, and Malte Hagener. Filmtheorie zur Einführung. Hamburg: Junius, 2017.

Goulding, Daniel J. Liberated Cinema: The Yugoslav Experience, 1945–2001. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002.

Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575–599.

Ishizuka, Karen L., and Patricia Rodden Zimmermann, eds. Mining the Home Movie: Excavations in Histories and Memories. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.

Jenkins, Keith. Re-Thinking History. London: Routledge, 1991.

Kracauer, Siegfried. “Erfahrung und ihr Material (1960).“ In Texte zur Theorie des Films. Edited by Franz-Josef Albersmeier, 234–240. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2003.

Kracauer, Siegfried. History, the Last Things before the Last. New York: Oxford University Press, 1969.

Kusters, Paul. “New Film History: Grundzüge einer neuen Filmgeschichtswissenschaft.” montage AV 5, no. 1 (1996): 39–60.

Lyotard, Jean-François. The Post-Modern Condition. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984.

Marušić, Antonela. “Dunja Ivanišević, Redateljica Prvog Domaćeg Feminističkog Filma ‘Žemsko’.” VoxFeminae. https://voxfeminae.net/strasne-zene/dunja-ivanisevic-redateljica-prvog-domaceg-feministickog-filma-zemsko/.

Nenadić, Dijana, “Tatjana Ivanišević – Dunja (1942–2014). Odlazak prve ‘žemske’ hrvatskog eksperimentalnog filma.” Novosti. Hrvatski Filmski Savez. http://www.hfs.hr/novosti_detail.aspx?sif=3376#.Xyfzr69xeUk/.

Nenadić, Dijana. “'Splitska Škola' između klupske i osobnih mitologija/'split School' Between Club and Personal Mythology.” In Splitska Škola Filma/Split Film School: 60 Godina Kino Kluba Split/60 Years of Cine Club Split. Edited by Sunčica Fradelić, 41–98. Split: Kino klub Split, 2012.

Paul, Gerhard, ed. Visual History: Ein Studienbuch. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2006.

Riederer, Günter. “Film Und Geschichtswissenschaft: Zum Aktuellen Verhältnis Einer Schwierigen Beziehung.” In Visual History: Ein Studienbuch. Edited by Gerhard Paul, 96–110. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2006.

Roepke, Martina. “Crafting Life into Film: Analysing Family Fiction Film from the 1930s.” In Small-Gauge Storytelling: Discovering the Amateur Fiction Film. Edited by Ryan Shand and Ian Craven, 83–101. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013.

Szijártó, István. "Four Arguments for Microhistory.” Rethinking History 6, no. 2 (2002): 209–215.

Shand, Ryan. “Amateur Cinema: History, Theory, and Genre (1930–1980).” PhD thesis, Department of Theatre Film and Television Studies, University of Glasgow, 2007. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4923/1/2007shandphd.pdf.

Shand, Ryan. “Theorizing Amateur Cinema: Limitations and Possibilities.” The Moving Image 8, no. 2 (2008): 36–60.

Shand, Ryan. “Introduction: Ambitions and Arguments – Exploring Amateur Cinema through Fiction.” In Small-Gauge Storytelling: Discovering the Amateur Fiction Film. Edited by Ryan Shand and Ian Craven, 1–30. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013.

Shand, Ryan, and Ian Craven, eds. Small-Gauge Storytelling: Discovering the Amateur Fiction Film. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013.

Sklar, Robert. “Moving Image Media in Culture and Society: Paradigms for Historical Interpretation.” In Image as Artifact: The Historical Analysis of Film and Television. Edited by John. E. O'Connor, 119–135. Malabar: Robert E. Krieger, 1990.

Toro, Fernando de. “Explorations on Post-Theory: New Times.” In Explorations on Post-Theory: Toward a Third Space. Edited by Fernando d. Toro, 9–23. Frankfurt am Main: Vervuert Verlagsgesellschaft, 1999.

Vivo, Filippo de. “Prospect or Refuge? Microhistory, History on the Large Scale.” Cultural and Social History 7, no. 3 (2010): 387–397.

Vukašinović, Višnja . “Žemsko – Njena četiri zida.” https://www.dokumentarni.net/2017/10/02/zemsko-njena-cetiri-zida/.

Wiesenthal, Christine, Brad Bucknell, and William John Thomas Mitchell. “Essays into the Imagetext: An Interview with W. J. T. Mitchell.” Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal 33, no. 2 (June 2000): 1–23.

Zimmermann, Patricia R. “Geographies of Desire: Cartographies of Gender, Race, Nation and Empire in Amateur Film.” Film History 8, no. 1 (1996): 85–98.