Zinovii Tolkachov’s Graphics from the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek Death Camps

Testimonial Works, Viewer’s Perception, and Uses in Political Propaganda

Table of Contents

Soviet Film Footage and Professional Practices (1941–1945)

Towards a History of Soviet Film Records (Kinoletopis')

A Travelling Archive

Zinovii Tolkachov’s Graphics from the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek Death Camps

People with Disabilities as Nazi Victims on Screen and Paper

Forgotten: Film Documents from the Liberated Camps for Soviet POWs

Depicting Atrocities

Reflections on the Geography of the Holocaust Based on Soviet Film Footage

Soviet Footage from the 1940s and the Holocaust at Babyn Yar, Kyiv

Filming Auschwitz in 1945: Osventsim

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Vyshislavsky, Glib. “Zinovii Tolkachov’s Graphics from the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek Death Camps: Testimonial Works, Viewer’s Perception, and Uses in Political Propaganda.” Research in Film and History 6 (2025): 1–38. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/23566.

Some works by artists – painters and graphic artists – differ significantly from the main body of images created over the last centuries. They contain information uncomfortable to the viewer that modern terminology would usually label as scenes of violence and intolerance. It is difficult to classify them in accordance with the aesthetic category of the beautiful. They present a different kind of aesthetics. They do not have the épatage of actual works of art. The paintings and graphics in question are serious and tragic. They are dedicated to real historical events. These include, for example, Francisco José de Goya’s The Disasters of War, works by George Grosz, Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Christian Schad, and Zinovii Tolkachov. These artists created testimonial works. Like documentary photographs, their creations show us the tragic events of history. They seek to have an impact on the viewer.

This article analyses the circumstances that contributed to the creation of artistic drawings – historical testimonials – in Zinovii Tolkachov’s work and the graphic series “Majdanek,” “Flowers of Oswiecim,” “Oswiecim,” about camps that the author visited immediately after the liberation. It discusses and highlights the context of political and historical events, the author’s involvement in the scenes he depicts, as well as the use of specific artistic means of expression. These testimonial works combine the subjectivity inherent to artistic images, with the accuracy of historical details. This results in a great persuasiveness and powerful influence on the viewer. On the other hand, like any testimony, Tolkachov’s drawings were far from always being convenient to the authorities. After a period of active co-operation, Tolkachov fell out of favour with the authorities and experienced social isolation. However, most often, viewers perceived his drawings as a sincere condemnation of the Holocaust, of cruelty, inhumanity, aggression, and as a truthful testimony of historical events.

Artistic Creativity at the Service of Power in the USSR

Zinovii Tolkachov (1903–1977) was born in Shchedrin, Minsk province. In 1913, the Tolkachov family moved to Kyiv, where Zinovii studied at the Jewish Treasury School (1914–1915). In 1916–1917, he became an assistant poster artist. In 1918, he joined the Komsomol and, at the age of 16, he participated in the activities of the Komsomol units to fight with the peasants of Ukraine to strengthen the power of the Bolsheviks: he became an agent tasked with grain requisition in the organisation “Ukrainian military billets“1 and also created posters by order of the Political Department of the Kyiv District Military Committee. In 1920, he studied for several months in Moscow in the famous educational institution VKhUTEMAS with Peter Konchalovsky and Alexander Osmerkin. In the same year, he fought with the Red Army in Ukraine. During 1921–1922, he was head of political education in the district committee of Komsomol units in Kyiv, where he also worked on the club’s monumental murals, which glorified the activities of the Komsomol and Communists. Survived reproductions show that the murals’ narratives emphasised the importance of collectivism under the leadership of the Party. They portrayed the figures of leaders, giant in scale, gesturing to direct the innumerable masses of impersonal people. In addition, the artist created easel graphics, posters, illustrated books. The aesthetics of his works were close to German Expressionism.

In the 1920s, the artist became a member of the Communist Party and at the same time fought as a private soldier in the active army in Kremenchug and Sukhumi, managed the magazine Young Bolshevik in Kyiv, was the Secretary of the Bureau of Workers’ Correspondents, studied at the “Communist University” named after Artem in Kharkov, and studied at the Kyiv Art Institute with Fyodor Krichevsky and Mikhail Boychuk.2

Tolkachov was not only a convinced Communist, he was also an important collaborator to the authorities when it came to ideological influence over the population. His energy was appreciated – the artist and Red Army soldier was quickly moving up the career ladder. In 1930, he was appointed to a dean of the Kyiv Art Institute and professor of the graphic arts faculty. This can be explained by the fact that in the RSFSR and USSR of the 1920s and 1930s, appointments to high-ranking positions depended more on loyalty to the Party than professional experience or the candidate’s age.

In the 1930s, the aesthetics of Tolkachov’s works changed further to a shift in the position of the USSR’s authorities towards diversity in art. Representatives of avant-garde were persecuted and Socialist Realism became the only style that was supported by the State after 1934. Tolkachov’s former sympathies for an expressive style became barely visible.

The authorities’ support of Tolkachov as a Communist artist is also reflected by the fact that his works were sent to exhibitions meant to display the achievements of Soviet power and to positively influence its public opinion in other countries. Several examples include the exhibition of Soviet fine art in Winterthur (1929), London, and other cities of Great Britain (1930), in Zurich, Bern, Geneva, Basel, St. Galen (1931), the exhibition of Ukrainian Soviet graphics in Prague (1931), the exhibition of Soviet art in Japan (1932), as well as in Madrid, Warsaw, Copenhagen (1933), and in New York (1940).3

During the war between Germany and the USSR, Tolkachov continued to be at the service of the Red Army. As an important worker in the field of ideology, he was not sent to the front, but was tasked with organising propaganda exhibitions deep in the rear, among the evacuated population. The army’s command gave the artist leave to travel around the country to arrange exhibitions in Pyatigorsk (1942) and in Mary, Armavir, Ufa, and Moscow during 1942–1944.4 Paintings and graphics were created shortly before the exhibitions. The author himself compiled these works and named the series “Occupants.”

The drawings were meant to leave viewers with an emotional charge that was stronger than a documentary photograph. The artist drew numerous scenes of brutal acts of cruelty, violence, murder, and abuse from the occupiers. The characters’ features were very generalised and did not go into details except for the division between “one’s own – another,” with the aggressor depicted as infinitely evil and the victim absolutely defenceless, thus bringing the author closer to a certain form of simplicity. Such drawings were meant to elicit a thirst for revenge in the viewers. The works were drawn in pencil, charcoal, or painted in watercolour and gouache. In terms of style, they are close to naturalistic realism (Figures 1–2).

Overall, the series “Occupants” was significantly conditioned by ideology. It illustrates the main narratives developed by the Soviet authorities about the enemy: its sadism, greed, and arrogance. The Holocaust theme, so expressively manifested in later drawings, was not emphasised in this series. Since the artist himself was not at the front at that time, his works lack direct impressions of life. Unlike the later series, in these, the author did not rely on documentary authenticity of details; on the opposite, they even lack hints of any specific place and time, of the state of nature, or of psychological nuances. Elements of authenticity can only be seen in some of the drawings: yellow marks on clothes (“Yellow Crosses,” 1942) or a badge with the name of the place of origin instead of a piece of jewellery around a woman’s neck (“Into Captivity,” 1943).

Author’s Involvement in the Depicted Events and the Overcoming of Ideological Schemes to Turn Works of Fiction into Historical Testimonials

In September 1944, the Political Department of the 1st Ukrainian Front commissioned Tolkachov to prepare works for the exhibition “Atrocities of the German occupantss” based on the facts that had been revealed during the liberation of concentration camps. To do so, the artist was granted “a business trip to the Lublin and Majdanek district for the period between 16 October and 5 November, 1944...”5 where the extensive system of Majdanek and Auschwitz death camps was located, some of which had only recently been liberated during the Red Army’s offensive.

For several months (from the author’s memoirs, more than 35 days were spent in the Majdanek camp alone), the artist recorded as many testimonies as possible. According to the words of the artist himself (first published in 1970 in the book Auschwitz),6 he walked around the “mechanised death factory,” talked to witnesses – newly liberated prisoners who were still in the barracks, drew, wrote, and tried to remember. In 1945, the author divided hundreds of drawings into several series: “Majdanek” was created directly in the Majdanek camp. “Flowers of Oswiecim” in the Birkenau-Brzezinka camp and “Oswiecim” was started in the camp during Tolkachov’s second mission in February–March 1945. Some of the images were sketches from life, others were created on the basis of sketches made a few hours or days later, in the neighbouring villages where the artist stayed during his trip and where he had set up an improvised art studio. The series “Oswiecim” was continued after 1961 as paintings (the obsolete name Oswiecim is used instead of “Auschwitz-Birkenau,” because that is how Tolkachov signed the works).7

The artist’s personal involvement set these series apart from the schematic and detached drawings he made in the series “Occupants.” What he saw in the death camps significantly shook the artist’s consciousness and led to many changes in his creative style. The drawings themselves, made from life, acquired the valuable quality of witnessing historical events. As opposed to illustrating stories he had heard and themes developed by propagandists, he now testified himself. In addition, Tolkachov managed to combine the emotional elements of artistic works with the accuracy of documentary photography. At the same time, the artist’s use of photographs as auxiliary material in the process of drawing is not traceable in any way.

His desire not to narrate but to reproduce, not to reproduce but to “take a piece,” was manifested in the peculiar transfer of reality into drawings. For example, the artist used forms from the Auschwitz commandant’s office (Oswiecim (Auschwitz)), as well as forms from the company that supplied poisonous gas, “I. G. Farbenindustrie” as drawing paper. This reinforces the effect of presence and borrowing – a peculiar inclusion of the ready-made technique. Another artistic technique connecting the works with the event they depict is the combination of drawings and comments that complement the image in one composition. There are also recordings of conversations of the depicted characters and the author’s impressions of what he has seen (Figures 3–5).

Some of the texts mentioned above were published under the title “From the artist’s notes” in 1970.8 These are vivid descriptions of the author’s impressions, which confirm his emotional immersion in the events:

together with the commission to investigate Nazi crimes, I went to Birkenau, one of the Oswiecim camps. Again, the wide massifs girdled with barbed wire <...>. A succession of freight trains were coming from all over Europe, packed to capacity. A succession of carriages of death, packed with people who had lost track of their misfortunes, travelled together with those who suffocated, died on the way. At the station, the SS sorted the people: some were sent to hard labour, and most were condemned to suffocation and burning. Few were left alive in this barbaric den. And again, I am walking through the devastated barracks. On both sides – three-storey bunks. This is where they lived. Tormented, struggling and hoping for liberation <...> Three tiers for women, for children. Three tiers of hopelessness. Outside the walls, the crematorium ovens awaited them. Hollow roofs. Everything was mixed together: corpses, clothes, dirty rags. Black sheds filled to the brim with corpses. Oh those blatant dead heads! <...> They stand unceasingly before my eyes.9

The artist’s imagination led him to paint himself as a prisoner; in “The Way There” (1945), we see a combination of visual and verbal messages. A character dressed as a prisoner looks back at a snowy path that leads to ominous structures under a black sky. His hand is gesturing, it is as if the man is defending himself from what he has seen. At the same time, in the corner of the picture is written the following: “I see again in enlarged size the samples of Majdanek. Gas chambers again. Jars of Zyklon. Frozen corpses. Blown up crematoria. Auschwitz station. In front of my eyes a train not sent to the Reich. Wagons with hair. <...> Executioners!!!” (text on the drawing by the artist’s hand).10 This image can be seen as Tolkachov’s internal self-portrait. That is, it depicts a character who outwardly does not resemble the artist but who has the thoughts and feelings of the author. Tolkachov’s expression of empathy is inherent to his work, but it is especially present in the series “Oswiecim.”

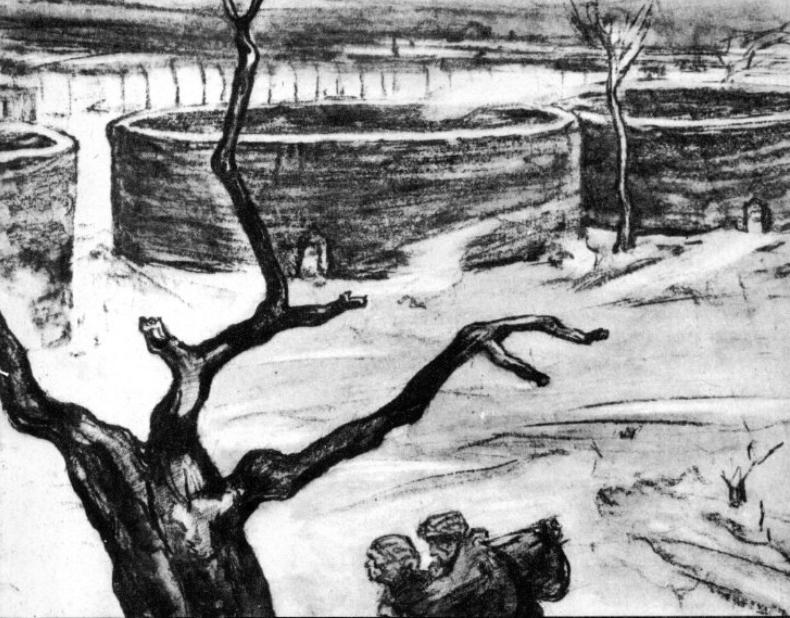

An important artistic means that Tolkachov widely used in the drawings he made at that time was to attribute to things human character and elements – feelings. The author wrote: “The winter wind rages over Oswiecim, girdled with three rows of barbed wire. It seems as if not the wire, but the tortured earth itself moans with the voices of the dead.”11 What he saw and the impressions it left on him helped the author imagine and depict in drawings what was happening in the gas chambers and barracks of the camp, a few months before liberation. The way nature is depicted reflects the psychological state of the artist – in “Brzezinka” (1945) the doomed tree against the gloomy sky seems blackened with sadness. Barbed wire hangs from its branches, and a little further away, illuminated by an occasional disturbing ray, one can see the characteristic curved camp posts with wire.

The author begins the album “Flowers of Oswiecim” with this drawing, as a prelude, and, as an afterword to the same album, he presents a landscape full of the author’s utmost expression – abandoned traces of chaotic and unkind human activity under a harsh sky that represents human grief – “Wasteland” (1945) (Figure 6).

In the series “Oswiecim” this figurative device is more developed. In the drawing “Home” (1945), the remnants of branches on a tree resemble blackened hands that seem to release the prisoners. On the sheet titled “Landscape” (1945), instead of the usual beauty of the environment, the viewer sees a stump broken by an explosion against the background of the camp fence – an image of what is left of the tree, and, in general, of life itself in this terrible place (Figures 7–8).

Some of the drawings contain diagrams of gas chambers, plans of barracks, or consist entirely of handwritten text – stories of former prisoners about their fate and the fate of their relatives (Figure 9).

At the Majdanek exhibition in Krakow in 1946, Tolkachov exhibited items from the Majdanek camp alongside his drawings – prisoners’ clothing, everyday objects, and parts of the camp’s equipment. Thus, his works were not separated from other evidence. The exhibition was designed to highlight how the drawings were one with the event of which they were a part. As indicated in the text accompanying one of the exhibitions of 1945, the tragic reality “has not yet cooled down, it leaves distinct reflexes on the pictures shown at the exhibition.”12

The fact that the author became not only a translator of historical events, but also came as close to them as possible, turned into their eyewitness, and in his imagination was even a participant, is confirmed by a change in his style. There was a shift in the drawings, which, as professionals know, speaks of profound changes in the author himself. Instead of the realistic manner imposed by the Soviet authorities after 1934 and used by Tolkachov in his series “Occupants,” the artist returned to the expressive style he had practised in the 1920s. Of course, this was more appropriate for conveying the tragic events and the psychological state of the author:

The headlights pierced the night. The snow pierced the car windows. My companions were silent. I raised my collar and pulled myself into the soldier's overcoat. I huddled in the corner of the seat. No one could see me. A sudden shiver gripped my whole body. They would not leave my memory. My whole being could not tear itself away from that sinister corner of the earth that was left behind me, from that terrible human abyss. I shuddered all over with silent sobs.13

As such, the author’s involvement in the events he depicted, the artist's imagination, and his empathy for the prisoners of the camps allowed him to free himself from the schematism of ideological drawings and bring his work closer to the historical reality in all its harshness. This is how Tolkachov’s drawings became historical testimonies.

Perception of Tolkachov’s Works by Contemporaries in Poland and Inconvenient Drawings: Evidence for Kremlin Propaganda

Between 1944 and 1946, Tolkachov’s exhibitions were held in many cities in Poland. The series “Majdanek” (39 works) was presented in Lublin (November 1944) and then in Kraków, Katowice, Łódź, Rzeszów, and Warsaw (1944–1945). The series “Flowers of Auschwitz” (36 works) was presented in Kraków, Katowice, Łódź, and Warsaw in 1945. According to the artist, these exhibitions were attended by 118,030 visitors (dates, locations, and number of visitors are taken from Tolkachov’s manuscript “Reporting note to the head of the USSR Military Mission in Poland” from July 2, 1945.14 Works from both series were combined in an exhibition in Krakow (1945) and were then presented in Vienna (1946) under the title “Majdanek, Auschwitz.”15

The perception of these testimonial drawings varied and largely depended from the political context in which the viewer was situated. In the visitor’s books preserved in the archive of the Centre for Research on the History and Culture of Eastern European Jewry (Kyiv),16 we can find entries in many languages: Polish, Russian, French, Yiddish, Czech, Italian, Greek. Among the people who left messages, there were schoolchildren, soldiers, and former prisoners of the camps. Most of them took the opportunity at least in this way to tell and thereby immortalise some experience from their own lives relative to the war or the camp. The visitor’s book helped publicise and spread thoughts. The comments were also addressed to other attendees or entire nations. While art critics looked at the quality of the works, ordinary visitors reacted primarily to the story. The main theme that can be found in their messages was the horror of what was depicted, and those who had experienced similar things themselves wrote that they could not hold back their tears. These visitors added their camp number to their name in the caption.

Almost every entry ended with words about the need for revenge: “Death to the German executioners” (entry in Polish from the visitor’s book of the exhibition “Flowers of Auschwitz”17); “It is not for us to write and paint, it is for us to act” (entry in Polish from the book of reviews of the exhibition "Flowers of Auschwitz"18); “Fascism is misery and suffering, it is war and poverty <...> beat them everywhere; the more, the longer the peace will last” (entry in Russian from the book of reviews of the exhibition “Flowers of Auschwitz”19).

Polish schoolchildren in Rzeszów wrote essays full of emotion about the exhibition:

A series of Tolkachov’s paintings are before my eyes: crematorium ovens, gas chambers. With a cruel and cynical smile on the faces of the Nazis <...> this cruelty is boundless, it seems to me that it is a mirage. I stand in front of a painting where a ruthless hand crushes a photograph of a smiling mother and child. Finally, I walked out because I realized I didn’t have the strength to look. I feel this chaos that destroys my thoughts and feelings <...> These are the many evidences of the cruelty inflicted on our parents. Can I really forget this? No, a hundred times no! We will always remember the blood spilled by our brothers and we will strive to avenge you!

(Irena Majoninska, pupil of the gymnasium in Rzeszow. From the visitor’s book for the “Majdanek” exhibition20).

Aside from the visitor’s emotional response, one can also see their ambiguous attitude towards the exhibition; not to the subject of the tragedy of the Holocaust, but to the fact that an exhibition of a Soviet artist was being held in Poland – a State that did not want to pledge allegiance to Moscow and fall within its area of geopolitical influence. In addition, the style of Tolkachov's works came across as archaic to the local viewers and differed significantly from the Polish, in fact European, system of artistic visuals. Thus, it was inevitable that Tolkachov's works were perceived by its Polish viewers in the context of the already existing, albeit considerably deformed by the war, artistic life of the country. Therefore, the perception shifted in focus as the artist’s work was seen as that of someone who belonged to a different artistic school.

In the period between the two world wars, visual arts in Poland experienced the freedom to develop and interact with other cultures. For example, artists from the “K.R.” group (“Komitet Paryski”: Józef Pankiewicz, Tadeusz Makowski, Eugeniusz Zak, Henryk Kuhn, etc.) contributed to the rapprochement of Polish and French art and helped highlighting the achievements of French painters in Poland. Thanks to the exhibitions they would organize or participate in and their cooperation with colleagues in France, Paris became one of the centres of Polish art life, along with Warsaw and Krakow. In the 1930s, thanks mainly to Lviv artists of the Artes group, surrealism was gaining traction.21 Before that, as early signs of surrealism, there were unusual individual systems of content and form that offered the viewers to immerse themselves in the worlds of fairy tales and legends, in atmospheres of circus and theatre, or of children’s dreams and folk stories. In the works of Vladislav Skoczylas and Eugeniusz Zak, these were based on Art Nouveau. In the works of Tadeusz Makowski, elements of cubism and naive folk art were intricately combined. Tadeusz Kulisiewicz’s engravings combined critical issues with a realistic depiction of life, such as the miserable life of peasants in the series of engravings “Schlembark.” Polish artists were familiar with Expressionism (which was called the “New Objectivity Style”), Russian Constructivism, Neoclassicism, and Italian Futurism, which provided a wide range of stylistic diversity.

Against this colourful background with inclusions of avant-garde, Tolkachov’s works, despite the expressiveness of his aesthetics that dated back to German Expressionism, were perceived as art of realistic orientation: visitors’ notes document comments related to the “strict realism of drawings.”22 On the other hand, the tragic realities of the SS death camps, with their “otherworldliness,” could be reminiscent of surrealism. However, despite these differences in perception regarding the artistic qualities of the drawings, the persuasiveness of the testimonies invariably shocked the viewers.

Tolkachov also brought forward something completely new, which was felt throughout post-war Europe (primarily in England and Italy) – a trend that had not yet formed into a style and been given a name. It was Tolkachov's attention to the personality of each character, the personalism, empathy, which we have already mentioned as common features of his works throughout the war years. Later, this “attention to everyone,” to the “little man,” to the underprivileged in their hard everyday life, would become the main theme in the works of the “Angry Young Men” (Britain) and of neo-realism in Italian cinema.

The emergence of this “post-war personalism” in contemporary European art was a reaction to the previous long domination of collectivism in the political and socio-cultural spheres. After all, it was collectivism that made the flourishing of dictatorships and mass support for ideologies of fascism, national socialism, communism, Trotskyism, etc. possible. Artists in post-war Europe, who had experienced the horrors of unification, began to pay special attention to the recording of any manifestation of intimacy and personhood. These processes that were taking place in the European artistic environment did not influence Tolkachov directly, moreover, some of them were just emerging, but they are important to help shed light onto the overall trend of development in European post-war art. They explain the success of Tolkachov’s works among art historians in Poland, who, in the mid-1940s, already sensed the presence of elements of “personalism” in his drawings – one of the most important trends in art in post-war Europe, which then shaped many artistic movements.

At the same time, Tolkachov’s works found their way to the milieu of Poland’s politically unstable society. The authorities (the provisional government, which was steered from Moscow) deliberately used the subject matter of the works to strengthen their position in Poland by exploiting the theme of the horrors of Nazi occupation. According to the artist's letters, the author co-operated with his superiors, both in the military and within the party. In 1945, he wrote to his wife Ksenia:

One thing is important to note – I gave all my strength – I did everything for the Motherland. The war will pass. My children will grow up. They will be proud of their father. I didn’t disgrace my family name. And I did something for the Motherland. What? It’s hard to write in this letter. But understand that what I’ve done will go to Mr Stalin, Mr Roosevelt. Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill. It's already been published in the press. And the main thing is that I fulfilled my combat mission and, as they say, with glory. No nights without sleep, no constant labour. I had to forget about everything (I certainly did not forget you and my son – you were always in my heart) and give myself to my work. And here, in Krakow, I had to work hard days and nights. <...> I can’t wait for the day when I will see everyone.23

In order to better understand what the audience’s reaction to the artist’s exhibitions in 1945 was, a brief description of the problems of the political situation in Poland is necessary. There were two opposing views. The first was supported by the apparatus of the Representation of the Government of the USSR in Poland: “The overwhelming majority of the Polish population universally welcomed the Red Army units as a liberating army.” This “Reference” ends with the words: “The Polish population correctly perceives the great liberating role of the Red Army” (from the Information Reference of the Political Department, 1945).24 This confirms that pro-Moscow sentiments prevailed in some communities: “At the moment when the heroic Red Army is fighting on the ancient Polish borders on the Oder and eliminating the consequences of a thousand years of German pressure on the Slavic lands <...> we come forward to the hands of its glorious leader, Marshal Stalin, with an expression of deepest admiration and sympathy” (telegram from the chairman of the Polish-Soviet Friendship Union, 1945).25 However, these documents only repeated the propaganda rhetoric created in Moscow.

According to the opposite view of historical events, after the occupation of Poland by Germany and the USSR in 1939, as a result of the signing of the secret part of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the legal and internationally recognised government of the Second Republic of Poland was in France and from 1940 in London. The Army of Krajowa operated under its leadership and later on together with the British command, so did the Army of Władysław Anders. The government emphasised that in the conditions of the new (already fourth) partition of Poland, all orders of the occupiers – Germany and the USSR – were illegal.

This position made diplomatic communications between Britain and the USSR extremely difficult. In the end, for the sake of the anti-Hitler coalition, Poland's interests were forgotten. These circumstances greatly influenced the resistance movement, the actions of the Army of Krajowa and, later on, determined the negative attitude of the Poles towards the Yalta agreements and the new Communist government of Poland, established under Moscow’s leadership.

Tolkachov’s expositions were held against this background, rife with contrarian views and heated passions. Even on the pages of the visitor’s books filled in by the exhibition’s viewers, one can feel the echoes of the struggle for the future of Poland: the slogan “Long live the Polish-Soviet Union” was emotionally and repeatedly crossed out by someone (entry in Polish from the visitor’s book for the exhibition “Flowers of Auschwitz” 26), and some statements were completely covered over with ink.

Tolkachov’s exhibitions were the first cultural events of the newly established government. Therefore, they can be viewed and labelled as “presentational” for the new government. The author himself was employed by the “Representation of the Government of the USSR” under the “Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland.” A special document authorised him to “carry out sketches on the whole territory of the country.”27 One of Tolkachov’s letters mentions that the exhibitions were organised further to the personal order of the People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs of the USSR Vyacheslav Molotov, i.e. the most influential figure in Stalin’s entourage.28

The high level of support for the artist is evidenced by catalogues and albums printed in very high-quality ink and paper, given the post-war years. Individual books were even published several times (“Majdanek” was published twice in Warsaw in 1945 (3,150 copies) and so was “Flowers of Auschwitz” in Krakow in 1945 and 1946 (a total of 9,200 copies).29 The artist’s exhibitions once again served as a political tool: the albums “Majdanek” and “Flowers of Auschwitz” were sent on behalf of the authorities to the leaders of the States of the anti-Hitler coalition, and to military leaders and ministers of the Allied States.30

In 1946, Tolkachov’s exhibition “Majdanek, Auschwitz” was held in Vienna, in the USSR sector, as the city (and Austria) was divided, like Germany, into zones of influence for Britain, the USA, France, and the USSR. In the same year, judging by a letter from the Committee for the Arts, Tolkachov’s drawings were to be exhibited in the newly annexed Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia.31 Thus, the authoritarian power of the USSR used talented artworks with extremely emotional themes to increase its own authority as victors. Demonstration of the most negative features of the defeated opponent with the help of graphics was supposed to idealise the new power in the eyes of its detractors.

However, the USSR’s policy changed extremely quickly. After the end of the war, Stalin’s USSR again distanced itself from the West, and the task of “cooling down” post-war society was resolved by fighting the national consciousness of Ukrainians, Crimean Tatars, Moldovans, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, and many other peoples. The community of “Cosmopolitans” (from the Greek cosmopolis, i.e., “citizen of the world”), a definition that implied the Jewish population, was also subjected to repressions. At the same time, repressions against “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists” were taking place in Ukraine. Alexander Dovzhenko, Maxim Rylsky, and others were accused of nationalism. The next waves of persecution took place in 1950 and 1951. Because of them, the literati Yury Yanovsky, Andrei Malyshko, Volodymyr Sosyura and others suffered.

In this new context, the State propaganda ceased to use the Holocaust theme. All of Tolkachov’s exhibitions were cancelled and his participation in collective exhibitions was significantly restricted. Some of the repressions also affected the author’s fate, which was marked by social isolation and difficulty to find employment. Because of the harassment organised by the authorities, Tolkachov could not get prestigious positions, such as, for instance, returning to a management role in the department at the Art Institute. He was forced to work as a cartoonist for the magazine Peretz and as an illustrator for the children’s magazine Pioneria. According to biographical data,32 despite the harassment of the authorities, Tolkachov was still allowed to participate in exhibitions – annually in one or more exhibitions – except for 1949, when after a condemnation in the press and the Union of Artists, he miraculously avoided arrest. But the “quality” of the exhibitions had changed: they were no longer prestigious international expositions in London, Bern, Zurich, or Venice. In addition, the “filters” of the committees that created the exhibitions only allowed “neutral” works of the author to be exhibited – book illustrations and portraits. The contrast with previous years of success was significant.

Tolkachov’s Works Beyond Propaganda

At the end of the 1950s, thanks to another turn in Soviet policy, Tolkachov’s restrictions on his profession were eased. But it was only as of 1965 that he was able to exhibit some of the works from the series “Oswiecim” (participation in the exhibition of projects for the memorial to the victims of Babi Yar, Kyiv, 1965). Works of the series “Majdanek,” “Flowers of Oswiecim,” “Oswiecim,” and other cycles were only exhibited by relatives of the artist six years after his death – “Exhibition of works by Z. Tolkachov” (Kyiv, 1983). Soviet propaganda no longer used these works for its own purposes and, for the first time, they were exhibited not as political arguments, but as works of art and evidence of history. It was in this capacity that Tolkachov's graphics and paintings were presented at exhibitions such as “Beyond Borders of Understanding. The Catastrophe of European Jewry through the Eyes of Artists” (Kyiv, 2003) and “Tolkachov at the Gates of Hell at Majdanek and Auschwitz: An Artist’s Testimony” (Yad Vashem Auditorium, Art Museum, Har Hazikaron, Yerushalim, 2002–2003). Thus, Tolkachov's works continued to be appreciated as important testimonies to the brutal truth of the Holocaust in very different eras with different generations of viewers.

However, the unsightliness of the events depicted in the drawings and the starkness with which they are reproduced can lend to significant confusion to the viewer who is be used to seeing art images evoking the aesthetic category of the beautiful. Indeed, the drawings of the series “Majdanek,” “Flowers of Oswiecim,” and “Oswiecim” were created for a completely different purpose, it is difficult to imagine them as interior decorations in a residential house. They are meant to awaken consciousness and disturb society. In her essay “In Plato’s Cave,” Susan Sontag described the feelings of the viewer when confronted with such images.33 She writes about the painful rejection, discomfort, and unwillingness to look at a photograph of the place where mass shootings took place in the Dachau camp. She writes about the feeling of complicity of the beholder in the event that took place. A similar discomfort accompanies the viewer in the presence of Tolkachov’s drawings. Often the artist achieves this effect not by directly depicting the event, but by forcing the viewer to speculate on what he has seen. Nevertheless, some plots can traumatise the psyche of viewers. For example, the drawing entitled “The Story of the Rope” (which turns into a noose) depicts just the moment of “insight” of children’s consciousness into what awaits them in the near future. The state of the children crosses the acceptable boundary of the viewer’s emotional equilibrium. This composition, as well as many other works, such as “Patent No. 67,353,” “The Boot,” and “God with Us,” raises the question of the conventionally acceptable boundaries when it comes to the depiction of violence (Figures 10–11).

These boundaries are notoriously fluid and depend on the type of art and the state of society. For example, documentary cinema, poster graphics, and especially reportage photography or performance art, allow for a much greater thematic breadth and a more powerful influence on the psyche of viewers through scenes of violence. At the same time, and in accordance with the tradition widespread in the USSR in the second half of the twentieth century, easel art, with all its ideological load, still did not break the link with the aesthetic category of the beautiful (the exception being the works of non-conformists). But Tolkachov’s works remind us of the relativity of such traditions. They take the viewers out of their “comfort zone” and induce certain inner transformations. As a consequence, they cause either reflection or decisive rejection, similar to what art historian Alexander Kamensky expressed in 1948 about the series “Flowers of Auschwitz”: “a series of nightmares, compared to which the darkest fictions of Goya's inflamed imagination pale in comparison.”34

Thus, in his series of drawings of the death camps, the artist developed a different artistic tradition from that of the post-war period. It was one that existed in the 1920s, when the function of art was considered not to be the creation of conditions for aesthetic contemplation, but an ideological influence, even a form of revolutionary pressure on the viewer to prompt him into action. These were the tasks that avant-garde artists, especially muralists, set themselves when working on propaganda trains and when they decorated workers’ demonstrations, painted frescoes in factories, Komsomol clubs, and soldiers’ barracks.

Following his creative intuition, Tolkachov chose the most appropriate way of making an artistic statement about the tragedy of the Holocaust. It would have been unacceptable, even offensive to the memory of the victims, if the artist had tried to limit the terrible and sinister scenes of SS crimes against humanity to the aesthetic category of the beautiful. The last decades have seen significant changes in the consciousness of Ukrainian viewers. Restrictive norms in art have been blurred, leading Tolkachov’s works to be perceived without prejudice. It is helpful to see in Zinoviy Tolkachov’s legacy, the main things that previously remained obscured by politics, “norm” conventions or bias – the basic things that are works of art and testimonies of history.

- 1

The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine. https://www.judaicacenter.kyiv.ua/en/archive/.

- 2

For a detailed biography see: Glib Vysheslavsky, Svidok Holokostu: Artist Zinoviy Tolkachov (Kyiv: Dukh i Litera, 2022).

- 3

Vysheslavsky, Svidok Holokostu.

- 4

Certificate dated 21.09.1943, written out in Tashkent by the commander of the Okremoye Rifle Battalion. Certificate on granting leave to Z. Tolkachov. 21.09.1943. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, d. 3, file 3, p. 1.

- 5

Pirogov A. To the chief of the Lublin garrison. Command instruction, 1944. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, d. 3, file 12.

- 6

N. Matveeva, T. Savitskaia. eds., Zinovii Tolkachov: Osventsim: Albom [Zinovii Tolkachov: Oswiecim: Albom] (Moscow: Izobrazitelnoe iskusstvom, 1970).

- 7

After the capture of Poland by the troops of the Third Reich, authentic names were changed to German ones. The town of Oswiecim between Kraków and Katowice was renamed Auschwitz and became part of Upper Silesia's Prussian administration. On the outskirts of the city, the old brick barracks dating back from the times of the Austro-Hungarian Empire were completed and converted into a concentration camp; “Auschwitz-I” (in the literature printed in the USSR, it was called “Oswiecim”). It now houses The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Memorial Museum. Three kilometres from it, during the years 1941–1942, “Auschwitz-II” was built on a huge territory. Nearby there was a settlement with the Polish name Brzezinka, which the administration renamed Birkenau. In the literature of the USSR, it was also referenced as “Oswiecim” (hence the confusion), and in post-war Poland, “Auschwitz-Birkenau”, in order to distinguish Polish names from the negative associations of the past. Now there is a memorial to the Auschwitz-II-Birkenau camp. In addition, there was a whole conglomerate of more than 45 “Auschwitz-III” camps in the region, the largest of which was the camp near the village of Monowitz (or Monowice in Polish).

The modern name of the former camp “Auschwitz-I” and “Auschwitz-II” recorded in the literature as “Auschwitz-Birkenau” is more appropriate than “Oswiecim,” as it allows to distinguish between the terrible past of the occupation and the peaceful life of the Polish city of Oswiecim.

- 8

N. Matveeva, T. Savitskaia. eds., Zinovii Tolkachov: Osventsim: Albom [Zinovii Tolkachov: Oswiecim: Albom] (Moscow: Izobrazitelnoe iskusstvom, 1970), 19–22.

- 9

Zinovii Tolkachov, “Z notatok khudozhnyka [From the artist’s notes]” in Zhyvi tradytsii: Ukrainsky radiansky khudozhnyky khudozhnyky pro sebe i svoiu tvorchist [Ukrainian and Soviet Artists about themselves and their work], eds L.V. Vladich, I.M. Blumina (Kyiv: Mystetstvo, 1985), 129.

- 10

Anon. Zinovii Tolkachov : Osventsim : Albom [Zinovii Tolkachov : Oswiecim : Albom], 23.

- 11

Tolkachov, Z notatok khudozhnyka [From the artist’s notes], 129.

- 12

Anon. Zinovii Tolkachov : Osventsim : Albom [Zinovii Tolkachov : Oswiecim : Albom], 13.

- 13

Anon. Zinovii Tolkachov : Osventsim : Albom [Zinovii Tolkachov : Oswiecim : Albom], 11.

- 14

Zinovy Tolkachov to the Head of the Military Mission of the SRSR in Poland. [Reporting note], 1945. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, spr. 3, file 15. 3, file 15.

- 15

Vysheslavsky, Svidok Holokostu.

- 16

The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine. https://www.judaicacenter.kyiv.ua/en/archive/.

- 17

Zinovy Tolkachov. “The Flowers of Auschwitz.” Book of Reviews. Poland. 1945. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, pl. 8, no. 4, l. 28.

- 18

Zinovy Tolkachov. “The Flowers of Auschwitz.” Book of Reviews, l. 28.

- 19

Zinovy Tolkachov. “TheFlowers of Auschwitz.” Book of Reviews, l. 28.

- 20

Zinovy Tolkachov. Reviews of the exhibition Majdanek. Poland. 1945. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, spr. 8, no. 3, l. 2.

- 21

Dorota Jarecka. “Artist Among the Ruins. Art in Poland of the 1940s and Surrealist Subtexts,” in A Reader in East-Central European Modernism 1918–1956, eds. Hock B., Kemp-Welch K. and Owen J. (London: The Courtauld Institute of Art, 2019), 372–386, DOI: 10.33999/2019.40.

- 22

Tolkachov. “The Flowers of Auschwitz.”

- 23

Zinoviy Tolkachov. Letter without an envelope. Xerox copy. April, 1945. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, d. 2. folder 1, file 38, fol. 1.

- 24

From the information note of the Political Department of the 1st Ukrainian Front on the attitude of the Polish population to the Red Army in the areas of Poland liberated by the front's troops since 12 January 1945. Original. Typewritten text.: Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation [online] (1945). Home: Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation. URL: https://mil.ru/winner_may/parad/his_docs/more.htm?id=20187@cmsPhotoGall….

- 25

Telegram from the Chairman of the Polish-Soviet Friendship Union to the Supreme Commander-in-Chief expressing deep admiration and sympathy for the Red Army, dated 24 February 1945. Copy from telegraphic tape. Typescript: Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation [online] (1945). Home: Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation. URL: http://mil.ru/winner_may/parad/his_docs/more.htm?id=20190@cmsPhotoGalle….

- 26

Tolkachov, “The Flowers of Auschwitz,” l. 60.

- 27

Shatilov S. Credentials. 1945. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, cf. 3, file 14, fol. 1.

- 28

Zinovy Tolkachov. Letter to the Deputy Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars V. M. Molotov [on the back of the report to the member of the R.G.V. Council, Lieutenant-General Shatilov vid 3.10.1945] 1945. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, cf. 3, file 17zv.

- 29

Zinovy Tolkachov. Reporting note to a member of the radius of the R.G.V. Lieutenant General Shatilov. 1945. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, cf. 3, file 17.

- 30

Press service of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance “26 January – presentation of Zinoviy Tolkachov’s art works and digital museum collection “Ukratna. Kiev. Babin Yar.” (2017). Main: Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. 23 sichnia. https://www.kmu.gov.ua/events/249683014.

- 31

Paschenko. To the artist Tolkachov. Letter from the Committee for Arts under the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR dated 8 April 1946. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14. Op.1. Sp.3. File 21, fol. 1.

- 32

Drobyazko N. The main exhibitions of Z. Tolkachov. 2003. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, cf. 7.

- 33

Susan Sontag, “In Plato’s Cave,” in On Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977), 1–22.

- 34

Aleksandr Kamensky, “Artists of Ukraine,” Soviet Art 1095, no. 7 (Moscow, 1948): 3.

Drobyazko N. Main Exhibitions of Z. Tolkachov. 2003. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, spr. 7. 7.

From the information note of the Political Department of the 1st Ukrainian Front on the attitude of the Polish population to the Red Army in the areas of Poland liberated by the front's troops since 12 January 1945. Original. Typewritten text.: Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation [online]. (1945). Home: Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation. https://mil.ru/winner_may/parad/his_docs/more.htm?id=20187@cmsPhotoGallery.

Kamensky, Aleksandr. “Artists of Ukraine.” Soviet Art 1095, no. 7 (1948): 3.

Matveeva, N., Savitskaia, T. eds. Zinovii Tolkachov : Osventsim : Albom [Zinovii Tolkachov : Oswiecim : Albom]. Moscow: Izobrazitelnoe iskusstvom, 1970.

Jarecka, D. “Artist Among the Ruins. Art in Poland of the 1940s and Surrealist Subtexts.” In A Reader in East-Central European Modernism 1918–1956, eds. Hock B., Kemp-Welch K. and Owen J., 372–386. London: The Courtauld Institute of Art, 2019. DOI: 10.33999/2019.40.

Paschenko. To the artist Tolkachov. Letter from the Committee for Arts under the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR dated 8 April 1946. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14. Op.1. Sp.3. File 21, fol. 1.

Pirogov A. To the head of the Lublin garrison. Command instruction, 1944. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, d. 3, file 12.

Press-service of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory. “On 26 June – presentation of Zinoviy Tolkachov’s artworks and digital museum collection “Ukraine. Kiev. Babin Yar.” Home: Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. 23 January 2017. URL: https://www.kmu.gov.ua/events/249683014.

Shatilov S. Credentials. 1945. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, cf. 3, file 14, fol. 1.

Sontag, Susan. “In Plato’s Cave.” In On Photography, 1–22. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977.

Telegram from the Chairman of the Polish-Soviet Friendship Union to the Supreme Commander-in-Chief expressing his deep admiration and sympathy for the Red Army, dated 24 February 1945. Copy from telegraphic tape. Typescript: Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation [online] (1945). Home: Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation. URL: http://mil.ru/winner_may/parad/his_docs/more.htm?id=20190@cmsPhotoGallery.

Tolkachov, Zinovii. “Flowers of Auschwitz.” Book of Reviews. Poland. 1945. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, p. 8, no. 4.

Tolkachov, Zinovii. “From the artist’s notes.” In Ukrainian and Soviet Artists about Themselves and Their Work, eds. L.V. Vladich, I.M. Blumina, 127–133. Kyiv: Mystetstvo, 1985.

Tolkachov, Zinovii. “Z notatok khudozhnyka [From the artist’s notes].” In Zhyvi tradytsii: Ukrainsky radiansky khudozhnyky khudozhnyky pro sebe i svoiu tvorchist [Ukrainian and Soviet Artists about themselves and their work], eds. L.V. Vladich, I.M. Blumina, 127–133. Kyiv: Mystetstvo, 1985.

Tolkachov, Zinovii. Reviews of the exhibition Majdanek. Poland. 1945. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, spr. 8, no. 3, l. 2.

Tolkachov, Zinovii. Letter without envelope. Xerox copy. April, 1945. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, d. 2. folder 1, file 38.

Tolkachov, Zinovii. Letter to the Deputy Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars V. M. Molotov [on the back of a report to Lieutenant-General Shatilov, a member of the R.G.V. Council, dated 3.10.1945] 1945. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, cf. 3, file 17zv.

Tolkachov, Zinovii. Reporting note to Lieutenant-General Shatilov, a member of the R.G.V. radius. 1945. The Centre for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Centre). Archives of the Jewish heritage of Ukraine, f. 14, op. 1, cf. 3, file 17.

Vysheslavsky, Glib. Svidok Holokostu: Artist Zinoviy Tolkachov. Kyiv: Dukh i Litera, 2022.