How it works

The interactive article has an open non-linear structure. It is focused on four video essays that outline current research on the presented audiovisual materials. The video essays can be controlled by the four large buttons Start, Usage, Media, and Conclusion. By clicking on the previews, the user can get detailed information about the shown audiovisual materials. The menu items Usage and Media allow targeted filtering and sorting of particular objects.

The Auschwitz Tattoo in Visual Memory

The circulation of images is one premise for gaining an iconic status. The circulation, however, depends on a selection process. Not everything that was once recorded was later also used. Specific visual representations correspond to a certain situation better than others, while some depictions recall earlier—already iconic—compositions, and others seem to add symbolical meaning. For that reason, specific photographs or film sequences were selected for representing historical events, and in many cases those depictions are used again and again, sometimes even becoming metonymic placeholders for what had happened.

Digitisation intensified the circulation of historical photographs and film footage. This included the use of such footage as direct quotes, as well as indirect and implicit references to iconic images in filmic recreations or artistic works. By identifying and examining visual connections between liberation footage and its various visual manifestations, we can define networks of visual relations between historical imagery and their contemporary representations. We better understand why specific images or sequences become iconic. We can analyse how they are used and reused. We discover specific compositional patterns. We can reveal processes of de-contextualisation and iconisation, as well as attempts to re-contextualise and examine the historical origin of such footage.

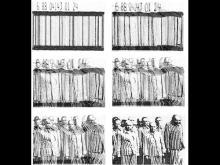

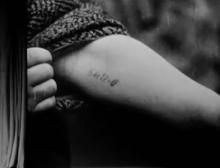

In this interactive audiovisual article, we explore this phenomenon by focusing on a specific example, namely the depiction of Jewish child survivors from the concentration and extermination camp at Auschwitz showing the numbers tattooed on their forearms. The three shots depicting the children in Auschwitz presenting their tattooed arms to the Soviet film camera are by no means the only visual documentation of Number Tattoos in the visual archive of the Holocaust. The first film compilations of liberation and atrocity footage that were edited in 1945 and 1946 contained also various other scenes with similar motifs.

We can think of many reasons why the particular shots of the children in Auschwitz circulated so widely, not only in the early atrocity films but also in later documentary and even fiction films, such as Stanley Kramer’s JUDGMENT AT NUREMBERG from 1961. The group of children, on the one hand, seemed to perfectly symbolize the innocent (not necessarily Jewish) victims of what was then perceived as ‘Nazi’ atrocities. The number, on the other hand, became a meaningful symbol for the process of dehumanisation, and finally turned into a metonymy for the transformation of humans into numbers. The gesture of presenting the Number Tattoo to the camera clearly recalled the presentation of Christ’s stigmata in the history of art. Furthermore, this gesture was inherently cinematic and corresponded perfectly to the revealing nature of the close-up shot. Finally, the children’s interaction with the camera seemed to directly address the audience as sympathising witnesses. Hence, it is no surprise that this particular sequence became a visual icon of the Holocaust.

As such, sequences like that of the children with the Number Tattoo started migrating into contemporary popular culture. Resembling what Marianne Hirsch (2012) has described as “postmemory”, those images “are migrating into popular culture as emblematic images” (Ebbrecht 2010). As part of 20th century commemorative culture—which constituted a significantly visual memory of the Holocaust—such migrating images became not only iconic for the Holocaust as a “master moral paradigm” (Ebbrecht 2010) for describing atrocity, they also established a rather ahistorical iconography that tended to be continuously dissociated from its historical origins. In doing so, the visual patterns of these representations are de-contextualized and inscribed into different histories and even totally fictional and dystopian settings. As emblematic images, however, migrating images are actually not memory cues without memory. On the contrary, they inherit particular relations to other images. That said, migrating images are significantly characterised by relationality and interconnectivity.

The migration of the Auschwitz Number Tattoo, for instance, reveals numerous multilayered relations. It demonstrates the iconic as well as the metonymic status of the motif, refers to it as an explicit expression as well as an implicit trace, introduces it as an individual mark and as a universal sign, evokes it in different historical contexts, emphasises specific compositional and gestural characteristics, and reflects on universal memory as well as on particular historical experiences.

Given the many visual manifestations of the Number Tattoo— a still image or as part of a sequence, a gesture, or a fragmented symbol—this section displays a diverse collection of usages of the Number Tattoo in a wide range of media environments. These examples are split between direct and indirect uses of the Number Tattoo. While the first refers to the appropriation of the archival material into a new (re)creation, the latter involves the use of the historical footage as a source of inspiration that does not form a direct indexical relation between the archival material and its later recreation.

The works presented in this section all show the Number Tattoo, therefore allowing us to examine the direct or indirect use of this motif as a migrating image. While many of the visualisations presented here are probably familiar to the viewer, they have not yet been shown together as part of a ‘Number Tattoo collection’. The ability to view them both individually and as part of a collection makes it possible to explore, compare, and identify the differences, as well as any similarities and hidden patterns that emerge from the various uses of this image as part of a larger network of image relations significantly characterised by relationality and interconnectivity. As befits migrating images (at least in the context of Holocaust imagery), the visual richness of the uses of the Number Tattoo thus allows viewers a glimpse into the mechanism of this visual and mnemonic phenomenon.

Direct usage

The actual historical sequence or parts of it are edited into another film or appropriated as a film sequence or film still into an artwork or installation.

When the actual historical sequence of the liberated children from Auschwitz presenting their tattooed forearms to the camera or parts of it is edited into another film or appropriated as a film sequence or film still into an artwork or installation, we consider this a direct use. This direct use constitutes explicit indexical relations to the actual visual source. This does not mean that the historical source material has to be utilised unaltered. In some cases, documentary and feature films include only parts of the three shots in their narrative. The original footage can also be cropped or visually transformed in various ways. For instance, the documentary THE LAST DAYS (USA 1998), for instance, superimposes the close-up of the Number Tattoo from Auschwitz with a panning shot along the forearm of a female survivor from Hungary who was interviewed for the film.

Most documentary films mediate the entire or parts of the sequence by editing it with other historical footage or testimonies. Some use voice-over or music in order to explain context or intensify the effect of the iconic images. Fiction films using the historical images often have a meta-mediating approach and present the sequence with the children as part of a film-in-film sequence.

Indirect usage

The images of the liberated children from Auschwitz showing their Number Tattoos are being recreated.

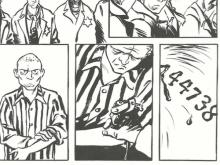

If the iconic images of the liberated children from Auschwitz are recreated, we define this as indirect use. The closest relation to the original footage would be a mimetic reenactment of content, composition and shot types as in THE NUMBER ON GREAT GRANDDAD’S ARM (2018), in which the sequence was accurately transformed into an animated film. In most cases, however, not the actual sequence but the motive of the Number Tattoo or the specific visual depiction in close-up are depicted in graphic novels, fiction films or artworks. This constitutes an analogy, referencing the historical source material. Such analogies can be manifold. Most artworks and graphic novels that are included in our collection evoke the Number Tattoo within the context of the memory of the Shoah. We see, however, that the motive was slightly detached from its original context and became a visual index of the Shoah survivor and his/her trauma. In those cases we can identify a rather generic use that utilises the visual icon for a general representation of survivors without paying attention to the historical fact that only prisoners in Auschwitz received a Number Tattoo.

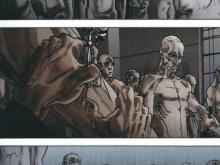

This generic use, however, can also lead to a more decontextualized appropriation of the motive, for instance as part of dystopian visions of future lives as in THE TERMINATOR (USA 1984), implicit references to related forms of humiliation and abuse as in the case of the medical experiments in STRANGER THINGS (USA 2016), or as resonating images in different historical contexts such as in the case of the graphic novel Palestine (1993).

In most cases, the Number Tattoo became a metonymy for the dehumanisation and objectification process imposed by the Nazis as well as for surviving persecution and humiliation.

- FilmBurger, Hanus1946Direct

- Filmn.a.1946Direct

- FilmLerski, Helmar1947Indirect

- FilmBlack, George R.1949Indirect

- FilmMaetzig, Kurt1950Direct

- ImageBezem, Naftali1953Indirect

- FilmHeynowski, Walter1961Direct

- FilmMorin, Edgar; Rouch, Jean1961Indirect

- FilmKramer, Stanley1961Direct

- ImageHoffman, Moshe1966Indirect

- FilmFruchtmann, Karl1969Indirect

- FilmGolan, Menahem1977Indirect

- FilmJarvik, Laurence1981Direct

- ImageFux, Pál1982Indirect

- FilmSchwartzman, Arnold1982Indirect

- FilmCameron, James1984Indirect

- Filmvon zur Mühlen, Irmgard1986Direct

- ImageSpiegelman, Art1986Indirect

- ImageBrenner, Frédéric1991Indirect

- ImageKahana, Vardi1992Indirect

- ImageSacco, Joe1993Indirect

- ImageStojka, Ceija1994Indirect

- ImagePassow, Beate1995Indirect

- FilmMoll, James1998Direct

- ImageSchechner, Alan2000Indirect

- FilmSinger, Bryan2000Indirect

- ImageKubert, Joe2003Indirect

- Żmijewski, Artur2004Indirect

- ImageEisenstein, Bernice2006Indirect

- FilmThalheim, Robert2007Indirect

- ImageHeuvel, Eric; van der Rol, Ruud & Schippers, Lies2007Indirect

- ImageMaor, Haim2008Indirect

- ImagePak, Greg & Di Giandomenico, Carmine2009Indirect

- ImageJacobsen, Sid & Colón, Ernie2010Indirect

- FilmCohen, Rob L.2012Direct

- FilmDoron, Dana; Sinai, Uriel2012Indirect

- ImageKichka, Michel2012Indirect

- ImageKichka, Michel2012Indirect

- FilmPetzold, Christian2014Indirect

- ImageKleist, Reinhard2014Indirect

- ImageKleist, Reinhard2014Indirect

- FilmMachineGames2014Indirect

- FilmEgoyan, Atom2015Indirect

- ImageIsraeli, Erez2015Indirect

- FilmDuffer, Matt2016Indirect

- ImageMastragostino, Matteo & Ranghiasci, Alessandro2017Indirect

- FilmSchatz, Amy2018Indirect

- ImageMorag, Debbie2020Indirect

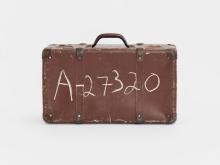

Häftling [prisoner]: I have learnt that I am Häftling. My number is 174517; we have been baptized, we will carry the tattoo on our left arm until we die.

The operation was slightly painful and extraordinarily rapid; they placed us all in a row, and one by one, according to the alphabetical order of our names, we filed past a skillful official armed with a sort of pointed tool with a very short needle. It seems that this is the real, true initiation: only by “showing one’s number” can one get bread and soup. Several days passed, and not a few cuffs and punches, before we became used to showing our number promptly enough not to disorder the daily operation of food-distribution; weeks and months were needed to learn its sound in the German language. And for many days, while the habits of freedom still led me to look for the time on my wristwatch, my new name ironically appeared instead, a number tattooed in bluish characters under the skin.

Primo Levi, Survival in Auschwitz. 1959 [1947]

In these powerful words, Primo Levi, one of the most famous of Auschwitz’s ‘Häftlings’, describes the humiliating experience of exchanging one’s personal identity for a serial number—just one of the series of dehumanising acts Nazi officials carried out on the deportees upon their arrival to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Requiring use on daily to satisfy the most basic needs, the Number Tattoo, as Levi explains, always brought with it the accompanying gesture of “showing one’s number”. Underlining the experience of life in the camp, this coupling—the serial number and its accompanying performative gesture—moved the Soviet liberating forces so that they took care to record it on film and in drawings almost as soon as Auschwitz was liberated. To raise awareness of the magnitude of the horrors they unveiled, the Red Army soldiers decided to focus specifically on revealing the stigmatised body of the (Jewish) child survivor. Thanks to its symbolic meaning and material visibility, the Number Tattoo has established itself in the post-war years as an emblematic image of the Auschwitz survivor, even of Auschwitz as a whole. Operating in this manner in a post-Holocaust era, with the circulation of the Soviet footage in post-war popular culture, the Number Tattoo has become a migrating image used and re-used by artists and filmmakers worldwide, thereby functioning as a visual model for depicting atrocities, both in explicit reference to the Holocaust and in other contexts. As a result, a network of connections has been, and continues to be, forged between the various manifestations of this migrating image, although each artist using the image naturally gives it a unique expression.

In this section we would like to draw your attention to media specificity; that is, the appearance of the Number Tattoo in various media environments. You are invited to reflect on the role media has played in the migration process of the Number Tattoo; does the choice of a specific medium also impact how the Number Tattoo is utilised? Is it possible to identify trends in visual manifestations that are unique to a specific medium?

Documentary Film

The iconic Number Tattoo sequence, consisting of the three shots including the close-up, was first used in the Soviet compilation film OSWIECIM/AUSCHWITZ (1945). Better known, however, is the first utilization of this sequence in the Soviet film KINODOKUMENTY O ZVERSTVAKH NEMETSKO-FASHISTSKIKH ZAKHVATCHIKOV: a one-hour film produced by the Soviet prosecution team screened in the courtroom at the Nuremberg Trials on 19 February 1946. Other early postwar films, such as DIE TODESMÜHLEN, integrated the sequence into a narrative of exposing the Nazi crimes to the German and international public.

Over the decades many documentary films used and appropriated the motive of the Number Tattoo. The constant reuse of the sequence with the liberated children from Auschwitz turned this scene into an iconic image of the Holocaust that was attributed first to Auschwitz and Auschwitz survivors and later to the trauma of the Holocaust in general. Only a few films tried to properly contextualise the sequence and mark it as liberation footage recorded by Soviet camera men after the liberation of Auschwitz. However, not all documentaries used the three consecutive shots showing the children and the close-up of the Number Tattoo. Some only appropriated two of the three shots or focused solely on the most recognizable—but less contextualising—close-up shot.

Turning it into a visual mark of survival, some documentary films shifted from the actual use of the historical footage from Auschwitz or other liberated camps to depictions of tattooed numbers of survivors. An early depiction can be found in CHRONIQUE D’UN ÉTÈ (France 1961), in which the camera suddenly reveals the tattoo on the arm of the young Auschwitz survivor Marceline Loridan during a conversation with students from African countries. The canonical documentary GENOCIDE (USA 1981) even used the motive of the tattooed forearm as an eye-catching symbol in its opening credits. The Israeli documentary NUMBERED (2012) solely focused on the Number Tattoo and features several artistic black-and-white depictions of the Auschwitz survivors’ numbers.

Fiction Film

Fiction films about the history and memory of the Shoah often use the image of the Number Tattoo as evidence symbolising the dehumanisation process imposed by the National-Socialists on their Jewish victims and marking the aftermath of the trauma of persecution. Some films even included the actual historical footage into their narrative; in most of these cases the sequence with the liberated children from Auschwitz is presented as a mise en abyme, a film-within-a-film projecting the evidence from the camps. Such is the case in JUDGMENT AT NUREMBERG (USA 1961) when the American judge and the German defendant can be seen witnessing the atrocities projected on the wall of the court-room that had transformed into a cinema. This is also present in a similar scene from RAT DER GÖTTER (GDR 1950), in which the courtroom evolves from the close-up of the indictment and then transforms into a cinema hall that presents the visual evidence from the camps, including the sequence with the Number Tattoo.

Most cinematic dramatizations, however, refer to the iconic image of the Number Tattoo by imitating the specific depiction of the tattooed forearm a in close-up. This can be seen, for instance, in IM LABYRINTH DES SCHWEIGENS (DE 2014), in which the close-up evokes the trauma of survival. Additionally, the opening sequence of the movie X-MEN (USA 2001) refers to it as an iconic sign indicating the personal background of one of the film’s protagonists, the mutant Magneto, as a survivor. Symbolising “the” survivor, the number can also become a misleading mark, for instance, in the film REMEMBER (CA 2015) that reflects the ambivalence of guilt and memory.

As a universal icon, the Number Tattoo also migrated into different narrative and historical contexts. It turned into a comprehensive reference indicating processes of dehumanisation, persecution, and abuse, for instance, in the science-fiction movie THE TERMINATOR (USA 1984) or in the TV-series STRANGER THINGS (USA 2016).

Art

Various artists work with the Number Tattoo, each of them engaging with its visual legacy in different contexts and through different mediums. Over the years, several famous artists have appropriated the Number Tattoo for their photographs, paintings, sculptures, videos, installations, and even performances. Some have used the image more provocatively than others (one is invited to reflect here on Artur Żmijewski’s iconic piece 80064 from 2004, or Claire-Fontaine’s 126419 from 2008). The examples presented in this section are a representative sample of various, sometimes surprising, visual manifestations and uses of the Number Tattoo in artworks created over the years.

Within art, the Number Tattoo sometimes undergoes fragmentation and reassembly. Some artists visually explore the gesture of the hand revealing the tattoo, while others focus on the number itself; a few artists draw upon personal memories and postmemories, while others ponder the collective meaning attributed to this well-known Holocaust icon. Occasionally, the viewer is offered a multi-layered meaning that goes beyond the historic event. However it is used, the aesthetics of the Number Tattoo present an invitation to consider how form complements content (and context), and how images supplement memories.

Graphic Novels

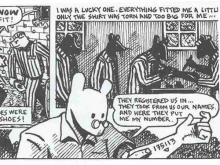

Since the publication of Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel “Maus – A Survivor’s Tale” (1980–1991) comics are increasingly acknowledged as acceptable media of commemorating the history of the Shoah, especially in its personalised and (semi-)biographical form. In “Maus”, Spiegelman tells the story of his father, an Auschwitz survivor, as a series of episodes. In the graphic novel Jews are presented as Mice and Germans as cats. Through this method, Spiegelman also introduced an approach to the (visual) history of the Shoah that is fundamentally based on the imitation and transformation of historical images and their adaptation to graphic illustrations. The Number Tattoo, however, is referenced by Spiegelman as a specifically corporal sign that indicates his father as a survivor, a symbol Spiegelman uses several times in contrasting ways. Similarly, Michel Kichka evokes the Number Tattoo in his graphic depiction of the story of his father in the book Deuxième génération (2012). For Kichka it is a mysterious sign that attracts the attention of his younger self.

The Number Tattoo became the expression of the authoritative voice of the survivor. This explains why the graphic novel Primo Levi (2017) opens with this motif. In this case, however, the number also serves as evidence of the process of humiliation and dehumanisation in the camps. Many graphic novels refer to this by recreating the actual moment of engraving the number in the forearms of the incoming prisoners.

Being significantly based on a sequential narration of segments that frame compositional patterns, graphic illustrations can also implicitly evoke the reference to the Number Tattoo as a migrating image. That is the case in the book Palestine (1993), which contains the close-up of a wounded forearm that resonates with the iconic footage of the liberated children in Auschwitz.

- FilmBurger, Hanus1946Non-Fiction Films

- Filmn.a.1946Non-Fiction Films

- FilmLerski, Helmar1947Fiction Films

- FilmBlack, George R.1949Non-Fiction Films

- FilmMaetzig, Kurt1950Fiction Films

- ImageBezem, Naftali1953Artworks

- FilmHeynowski, Walter1961Non-Fiction Films

- FilmMorin, Edgar; Rouch, Jean1961Non-Fiction Films

- FilmKramer, Stanley1961Fiction Films

- ImageHoffman, Moshe1966Artworks

- FilmFruchtmann, Karl1969Fiction Films

- FilmGolan, Menahem1977Fiction Films

- FilmJarvik, Laurence1981Non-Fiction Films

- ImageFux, Pál1982Artworks

- FilmSchwartzman, Arnold1982Non-Fiction Films

- FilmCameron, James1984Fiction Films

- Filmvon zur Mühlen, Irmgard1986Non-Fiction Films

- ImageSpiegelman, Art1986Graphic Novels

- ImageBrenner, Frédéric1991Artworks

- ImageKahana, Vardi1992Artworks

- ImageSacco, Joe1993Graphic Novels

- ImageStojka, Ceija1994Artworks

- ImagePassow, Beate1995Artworks

- FilmMoll, James1998Non-Fiction Films

- ImageSchechner, Alan2000Artworks

- FilmSinger, Bryan2000Fiction Films

- ImageKubert, Joe2003Graphic Novels

- Żmijewski, Artur2004Artworks

- ImageEisenstein, Bernice2006Graphic Novels

- FilmThalheim, Robert2007Fiction Films

- ImageHeuvel, Eric; van der Rol, Ruud & Schippers, Lies2007Graphic Novels

- ImageMaor, Haim2008Artworks

- ImagePak, Greg & Di Giandomenico, Carmine2009Graphic Novels

- ImageJacobsen, Sid & Colón, Ernie2010Graphic Novels

- FilmCohen, Rob L.2012Non-Fiction Films

- FilmDoron, Dana; Sinai, Uriel2012Non-Fiction Films

- ImageKichka, Michel2012Graphic Novels

- ImageKichka, Michel2012Graphic Novels

- FilmPetzold, Christian2014Fiction Films

- ImageKleist, Reinhard2014Graphic Novels

- ImageKleist, Reinhard2014Graphic Novels

- FilmMachineGames2014Fiction Films

- FilmEgoyan, Atom2015Fiction Films

- ImageIsraeli, Erez2015Artworks

- FilmDuffer, Matt2016Fiction Films

- ImageMastragostino, Matteo & Ranghiasci, Alessandro2017Graphic Novels

- FilmSchatz, Amy2018Non-Fiction Films

- ImageMorag, Debbie2020Artworks

This interactive article explored the migration of images, focusing specifically on the journey experienced by the Number Tattoo image as a representative case study: beginning with the liberation of Auschwitz in January 1945 and continuing through to contemporary popular culture. Because this migration process can be multi-directional—‘migrant images’ do not necessarily simply follow a one-way chronological trajectory—the article examined different directions in parallel. This examination has created a list of the primary reasons behind the transformation of this image into a migrant image. These include: the Number Tattoo as a symbol of the dehumanisation that the concentration camp inmates endured; the cinematic gesture of showing the hand in front of the cameramen (the origins of this gesture can be found in an earlier Christian iconography tradition, seen in the Christ’s stigmatised body); the children, as photographic subjects that evoke empathy; the special cinematic shot that ends in a close-up on a child’s tattoo. These reasons demonstrate the post-war appeal of the Number Tattoo image.

However, once an image begins circulating in the process of becoming a migrating image, it also takes on a (after)life of its own; as shown in this interactive article, a migrating image can appear in different media, can be used in different ways and for different reasons, or can even be assimilated into a different context. Nonetheless, deploying many representations simultaneously reveals the existence of an immense network of visual relations between the historical footage and its many later manifestations. This cannot be done without taking into account the images themselves; without this visual element, written text will struggle to explain the migration process that the image of the Number Tattoo went through.

Against this background, this article sought to offer a new way to study the relations that exist between different images, with the Number Tattoo as a migrant image serving as the connecting factor. It presents a variety of works that use the Number Tattoo, while analysing in more detail a number of representative examples from across the spectrum of media, artists, and purposes. These examples are composed into an interactive montage of moving and still images, sounds, and texts. This choice endeavours to offer multiple voices, each—individually and in combination—inviting the viewer-reader-user to continue exploring the migration process as a process that not only remains somewhat open to new interpretations, but also does not end with this article. The Number Tattoo continues its journey.

Annotated bibliography

General History

Holocaust Encyclopedia, United Stated Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Tattoos and Numbers: The System of Identifying Prisoners at Auschwitz.” Last edited December 9, 2019. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/tattoos-and-numbers-the-system-of-identifying-prisoners-at-auschwitz.

As indicated by the title, this encyclopedia entry—part of a much larger database created by the United State Holocaust Memorial Museum—offers a short introduction to the Nazi’s system of identifying prisoners at Auschwitz by means of a numerical tattoo.

Davidson, Deborah, ed. The Tattoo Project: Commemorative Tattoos, Visual Culture, and the Digital Archive. Toronto: Canadian Scholars, 2016.

This multidisciplinary collection of articles provides an extended social and cultural history of tattoos, with special attention given to commemorative tattoos and their implications for memory. Supporting a collective endeavour to create a digital archive of commemorative tattoos, the collection offers a unique bridge between theory and practice.

Hicks, Jeremy. First Films of the Holocaust. Soviet Cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 1938–1946. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012.

One of the most important sources for the visual history of the Holocaust is the footage and photographs taken by the Allied liberation forces. In this book, the author underlines the contribution of Soviet filmmakers to the documentation of the Nazi atrocities, and traces the uses of this horrific material by the Soviet government.

Shneer, David. Through Soviet Jewish Eyes. Photography, War, and the Holocaust. New Brunswick, London: Rutgers University Press, 2011.

The story of Soviet Jewish wartime photographers and the establishment of photojournalism stands at the centre of this book. Focusing on an elite group of Jewish photographers working in the Soviet Union, the author draws attention to the visual significance of their work in our understanding of Nazi atrocities.

Media and Memory

Anderson, Mark M. “The Child Victim as Witness to the Holocaust: An American Story?” Jewish Social Studies 14, no. 1 (2007): 1–22.

Focusing on the key role played by the figure of the child victim, this article explores the representation of this figure in various media environments, contextualising it within post-war American memory culture.

Baum, Rob. “‘And Thou Shalt Bind Them as a Sign upon Thy Hand’: Eve’s Tattoo and the Holocaust Consumer.” Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies 28, no. 2 (2010): 116–138.

Following Emily Prager’s novel Eve’s Tattoo (1991), the author analyses the contemporary fascination with the figure of the Holocaust victim (and sometimes survivors), identifying the postmodern performative character of Holocaust consumption; that is, the visitation of a neo-trauma on the Jewish body.

Baron, Lawrence. Projecting the Holocaust into the Present: The Changing Focus of Contemporary Holocaust Cinema. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005.

This book discusses various examples of films dealing with the Holocaust and argues that the Nazi’s genocidal plan for Europe’s Jews (“the Final Solution to the Jewish Question”) has stimulated cinematic imagination over the years. Organized according to specific periods and films, the author analyses the shifts in Holocaust memory and their resonance in popular culture.

Bloch, Alice. “How Memory Survives: Descendants of Holocaust Survivors and the Progenic Tattoo.” Thesis Eleven 168, no. 1 (2021): 107–122.

The central theme of this article is the replication of the Number Tattoo among Israeli descendants of Holocaust survivors. Contextualizing this trend within the genealogy of the Number Tattoo, the article interrogates the progenic tattoo in relation to private and public memorialisation.

Brouwer, Daniel C., and Linda D. Horwitz. “The Cultural Politics of Progenic Auschwitz Tattoos: 157622, A-15510, 4559, ...” Quarterly Journal of Speech 101, no. 3 (2015): 534–558.

In this article, the authors review the decision of descendants of Holocaust survivors to (re)tattoo their ancestors’ Number Tattoo on their own bodies. The authors explore the rhetoricity of this progenic tattooing phenomenon through semiotic, affective, and pedagogical registers.

Brutin, Batya. Etched in Flesh and Soul: The Auschwitz Number in Art. Berlin, Boston: de Gruyter, 2022.

This book focuses on the representation of Number Tattoo imagery in artworks created by various artists of different backgrounds and explores the ways the Number Tattoo is used by them to address contemporary issues.

Ebbrecht, Tobias. “Migrating Images: Iconic Images of the Holocaust and the Representation of War.” Shofar 28, no. 4 (2010): 86–103.

This article reviews historical footage from the liberation of the concentration camps, suggesting these should be understood as constituting visual models for later cinematic representations. Exploring the migration process undergone by liberation imagery, the author focuses on the decontextualized use of references to such iconic images in post-war popular culture.

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Tobias. “Preserving Memory or Fabricating the Past? How Films Constitute Cinematic Archives of the Holocaust.” Cinéma & Cie 15 (2015): 33–47.

In this article the author explores cinematic representations of the Holocaust within the framework of the archive, identifying different strategies for approaching the subject. Discussing feature films such as SCHINDLER’S LIST, THE PIANIST, EVERYTHING IS ILLUMINATES AND X-MEN, the author highlights the contribution of images, including the Number Tattoo, to this cinematic archive.

Erll, Astrid. “Travelling Memory in European Film: Towards a Morphology of Mnemonic Relationality.” Image [&] Narrative 18, no. 1 (2017): 5–19.

This essay deals with three recent ‘travelling memory-films’: AM ENDE KOMMEN TOURISTEN, WHOSE IS THIS SONG?, and CALAIS: THE LAST BORDER. These films address the transculturality of memory in Europe by showing or performing border-crossings on various levels. The essay introduces the concept of ‘mnemonic relationality’ and discusses three different processes of linking mnemo-cultural repertoires: dialogical, unreflexive and multidirectional. Emphasising the power of aesthetic forms in memory culture, the article demonstrates how plot-structures, the distribution of information, and editing techniques are forms that both represent and produce mnemonic relationality.

Hirsch, Marianne. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

A significant contribution to the field of memory studies, this book explores the transmission of traumatic memories to the ‘generation after’, which ‘remembers’ a past it did not experience, through the mediation of images, objects, stories, behaviours, and affects passed down within the family and the broader culture. Focusing on the work of post-generation artists and writers, the author dedicates a chapter to the image of the Number Tattoo (“Marked by Memory”).

Klik, Ella. “Customizing Memory: Number Tattoos in Contemporary Israeli Memory Work.” Memory Studies 13, no. 2 (2017): 6–49.

Concentrating on Israeli descendants of Holocaust survivors who decide to re-tattoo their relatives’ Number Tattoo, the author suggests a reference to the skin as a significant locus for postmemorial commemoration. This kind of bodily memorialisation, she argues, needs to be reflected on in the context of new media tools, socio-politics, and generational succession.

Schult, Tanja. “From Stigma to Medal of Honor and Agent of Remembrance: Auschwitz Tattoos and Generational Change.” In Entangled Memories: Remembering the Holocaust in a Global Age, edited by Marius Henderson and Julia Lange, 257–291. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter, 2017.

Based on some twenty examples of individuals who decided to replicate on their own bodies the number the Nazi forced upon their relatives at Auschwitz, this article explores the change in meanings of the Number Tattoo and the implications these have on our memory culture.