Indelible

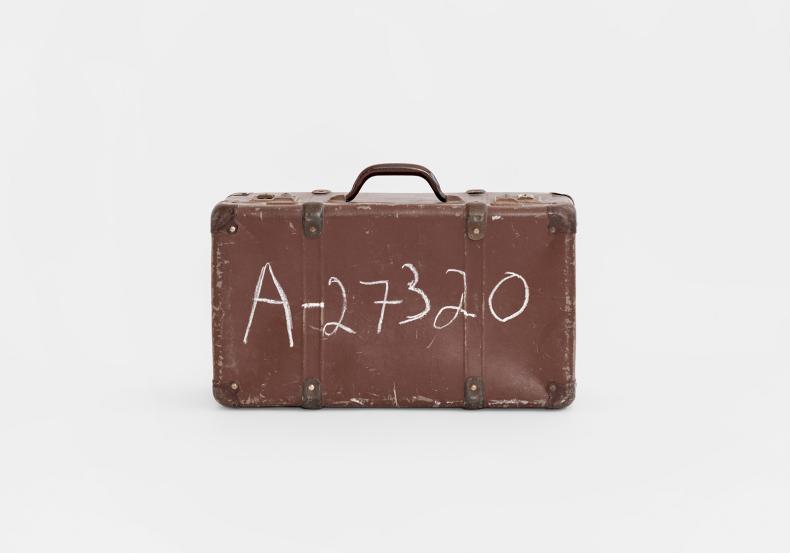

Debbie Morag, Indelible, 2020. Courtesy of the artist

Debbie Morag’s art is transformative; her camera functions as a healing tool. Born in Bergen Belsen Displaced Persons camp in 1948 (the year in which the State of Israel was founded) to Holocaust survivor parents, she is well acquainted with the “incomplete family, the great rift, the ‘no’ grandparents, the shadow that obscures the joy of life, the childhood that ranges from ‘normal’ to role reversal.” At home, as in the homes of other Holocaust survivors, there was a deafening silence about her parents’ wartime experiences. Reflecting on her own childhood, Morag sought out women who, like her, are the daughters of Holocaust survivor parents, of whom at least one parent was in Auschwitz during the war. Each woman (including the artist herself) was asked to dress in white and to hold an object belonging to at least one of her parents.

In A1479 (image no. 2), Shoshana Botvin holds a suitcase on which her parent’s ‘Auschwitz number’ was written in chalk. A ribbon is tied over her eyes; her gaze is directed inward. For Shoshana, as for the other ‘daughters of Auschwitz’, the Number Tattoo is – as Marianne Hirsch famously explained (in "The Generation of Postmemory") – a visual figuration of the transmission of the trauma to the children of the survivors; the number’s imprint is indelible, no matter how much one tries to erase it. Accordingly, the Number Tattoo image is more than simply a painful reminder of the atrocities the parental generation was forced to endure. Weaving together life and death, the portable and the stationary, memory and forgetfulness, Morag’s work reflects on both the ‘after life’ of the Number Tattoo image and the ‘life after’ the period in which the atrocities captured by the historical footage occurred.