Soviet Footage from the 1940s and the Holocaust at Babyn Yar, Kyiv

Table of Contents

Soviet Film Footage and Professional Practices (1941–1945)

Towards a History of Soviet Film Records (Kinoletopis')

A Travelling Archive

Zinovii Tolkachov’s Graphics from the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek Death Camps

People with Disabilities as Nazi Victims on Screen and Paper

Forgotten: Film Documents from the Liberated Camps for Soviet POWs

Depicting Atrocities

Reflections on the Geography of the Holocaust Based on Soviet Film Footage

Soviet Footage from the 1940s and the Holocaust at Babyn Yar, Kyiv

Filming Auschwitz in 1945: Osventsim

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Berkhoff, Karel. “Soviet Footage from the 1940s and the Holocaust at Babyn Yar, Kyiv.” Research in Film and History 6 (2025): 1–54. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/23568.

In the 1940s, film footage was recorded at the ravine of Babyn Yar, the main Holocaust site in Kyiv. This article presents the first systematic attempt to describe this footage, while excluding some material that appears to show the ravine but in fact does not. As I shall discuss, a substantial quantity of footage was shot, partly showing visiting foreign correspondents. In one case, sound was added on site. Camera operators also filmed inside the sand quarry where the Jews were forced to undress, and there was even a reenactment of the massacre.

The spatial and visual history of this killing site has been very challenging to reconstruct because the landscape has changed so radically — the ravine is no longer there. During my time as chief historian of the NGO Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center from 2017 to 2020, I pushed for an in-depth study of the matter, and in 2019 the centre’s supervisory board finally approved a budget. We assembled a team that included Ukrainian specialists Alexander Kruglov and Mykhailo Kalnytsky, and discussed much of the visual and supporting textual evidence, including some from my own collection. We also acquired and analysed German aerial photographs, whereby crucial contributions were made by Wacław (Willy) Godziemba-Maliszewski. In conjunction with textual sources, these visual materials served as the basis for the persuasive conclusions reached by the team’s leading researcher on this topic, historian Martin C. Dean. His findings were presented after I had departed from the memorial centre, most recently in Investigating Babyn Yar, a monograph that is essential reading for anyone interested in the topic.1

The catalyst for this spatial research on Babyn Yar was my discovery that various photographs from the post-Nazi period depict what appears to be the same lone tree on the distant horizon of the slopes of Babyn Yar; Figure 1 is just one example.2

This raised the question of how this vista could be reconciled with a now almost iconic photograph taken by the professional German photographer Johannes Hähle in early October 1941, which shows a wide ravine spur but seemingly not the lone tree3 (see Figure 2).

Dean established beyond doubt that these two photographs do indeed show two different spurs: a long, narrow spur in the black and white image, and a wide spur located further to the west and running less far into the distance in Hähle’s colour photograph. The lone tree is present in the latter image, but largely “hidden” against the background of other trees located further back (in the marked area in Figure 2). Dean also concluded that the site where Jews were shot and then buried (still alive, in some cases) on September 29–30, 1941 probably did not extend into the long, narrow ravine spur that can be seen in various Soviet photographs, but was limited to the wide “Hähle” spur to the west. The slopes of this spur that are visible in Hähle’s photograph were clearly steeper in places, because they had been blown up (to cover the corpses).4

There are also, however, other sources that have not yet been studied, including a few additional photographs and some film footage. No amateur film was ever made at Babyn Yar in the 1940s that we know of. But Soviet camera operators did record footage, some of which appeared in documentary (propaganda) films and, in one case, a fiction film. As long as they are studied alongside other sources, these kinds of visual materials can improve our understanding of the Holocaust killing site. Firstly, films are of enduring importance to those with an interest in commemorating the events in Babyn Yar, including people who lost relatives there. Secondly, they further clarify the site’s wartime history and early postwar appearance. Knowing what it looked like in the 1940s, based on film footage, strengthens our knowledge of what happened where and why precisely it happened there (since the location’s geographical features imposed certain restrictions). Thirdly, there is value in examining, if only in order to reconstruct Soviet memory politics, what Soviet camera operators filmed and which footage Soviet authorities allowed to be used.

This article presents the first systematic attempt to describe the relevant footage of Babyn Yar from the 1940s that exists, while simultaneously excluding footage that may appear to depict the ravine but in fact does not. The research would not have been possible without the support of French colleagues who worked on the project Le cinéma en Union soviétique et la guerre, 1939–1949 (CINESOV, 2012–2016), the related exhibition Filmer la guerre (Filming the War) that was held at the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris in 2015 and, later, the Visual History of the Holocaust project (launched in 2019).5 Their expertise was very helpful, as were the comments received from Martin C. Dean. My research on Babyn Yar was also supported by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s J. B. and Maurice C. Shapiro Senior Scholar-in-Residence Fellowship, by the Canadian NGO Ukrainian Jewish Encounter and by the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation.

This essay shows that a substantial quantity of footage was recorded, partly during a visit by foreign correspondents, and that there was even a reenactment of the massacre. In one case where sound was added on site (or rather, in one case where it is known to have been added — with archival records from the period stored in Russia, there is always a lingering doubt), this was done at the request of a Russian director. It also turns out that camera operators filmed inside the sand quarry, a hellish place where the Jews were forced to undress. The footage I analyse in this article was recorded at four different points in time: in November 1943, in early 1944, in late October 1944 (shoots for a fiction film) and in August 1946. I shall mostly discuss the material in that order, with a focus on questions of spatial history.

Footage from November 1943 Used in VICTORY IN RIGHT-BANK UKRAINE (1945)

Most or all of the footage recorded at Babyn Yar in November 1943 appears to have been part of a larger film project by the famous directorial couple Oleksandr (Alexander) Dovzhenko (Ukrainian, 1894–1956) and Iuliia Solntseva (Russian, 1901–1989). Dovzhenko was able to see Babyn Yar very early on; he flew into Kyiv with Politburo member Nikita Khrushchev on November 6, 1943, the very day the Red Army retook the city.6 By that time, Dovzhenko was on the verge of losing his standing with Stalin’s inner circle, which accused him of Ukrainian nationalism, and the planned film about Kyiv and Ukraine west of the Dnipro River was under strict ideological control right from the start.7

Certain segments of footage filmed at Babyn Yar ended up in Dovzhenko and Solntseva’s Soviet Russian-language documentary film VICTORY IN RIGHT-BANK UKRAINE AND THE EXPULSION OF THE GERMAN INVADERS FROM UKRAINIAN SOVIET TERRITORY / POBEDA NA PRAVOBEREZHNOI UKRAINE I IZGNANIE NEMETSKIKH ZAKHVATCHIKOV ZA PREDELY UKRAINSKIKH SOVETSKIKH ZEMEL', which was released in early 1945. Babyn Yar is seen for nineteen seconds.8 The Soviet paper trail is sparse, but this footage seems to have been filmed by camera operator Valentin Orliankin (1906–1999), very likely in mid to late November 1943. The voice-over that was added does not mention Jews.9 The footage starts with a three-second shot in which we can see nine people, viewed from behind, walking up to an edge. Slopes are visible in the background, but only very indistinctly, and the exact geolocation remains elusive10 (see Figure 3).

The second shot lasts eight seconds and begins with the camera tilting down. In this shot, thirteen onlookers, some in uniform, are seen from the front. They are representatives of the Soviet Extraordinary State Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes (ChGK). The shot ends deep down to reveal dead bodies, which had evidently not been exhumed during the SS’s secret Operation 1005 earlier that year11 (see Figure 4).

A picture taken by an unknown photographer and held in the ChGK archives in Moscow supports my supposition that this shot was indeed from Babyn Yar. Possibly taken nearby (but from another position), the picture in question has the Soviet caption “The corpses of Jews, inhabitants of Kyiv, shot in the ‘Babyn Yar’ ravine in 1943”12 (see Figure 5).

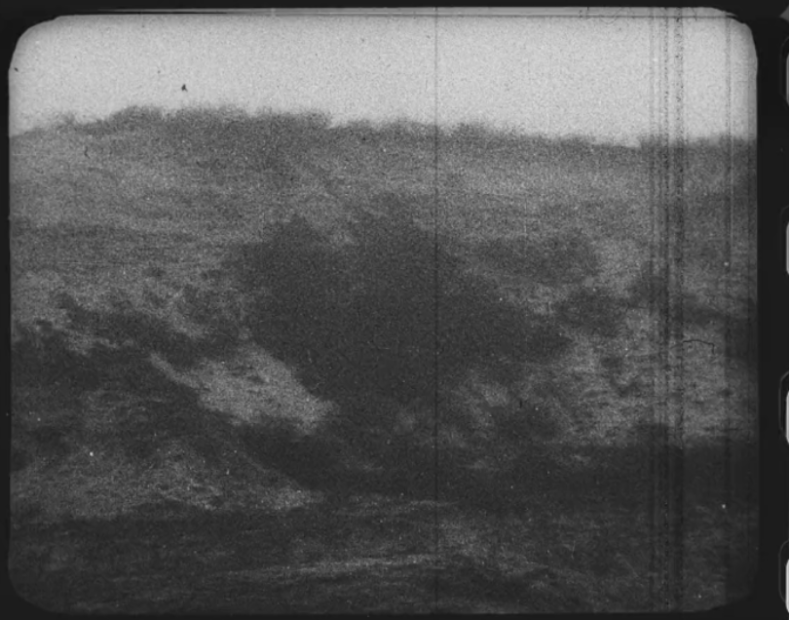

Orliankin’s third and final shot at Babyn Yar, also lasting eight seconds, was filmed from inside the wide western spur where the killings took place. He was standing at the bottom, which explains why the lone tree is seen on the horizon, unlike in Hähle’s photograph that shows the same spur from the same easterly direction (see Figure 6; compare with Figure 2).

Orliankin’s camera then pans from the right to the left, while also tilting down. Finally, it looks back, possibly capturing in the distance the spot where Hähle had stood two years earlier (see Figure 7).

Footage from November 1943 Used in FILM DOCUMENTS OF THE GERMAN FASCIST INVADERS’ ATROCITIES (1945)

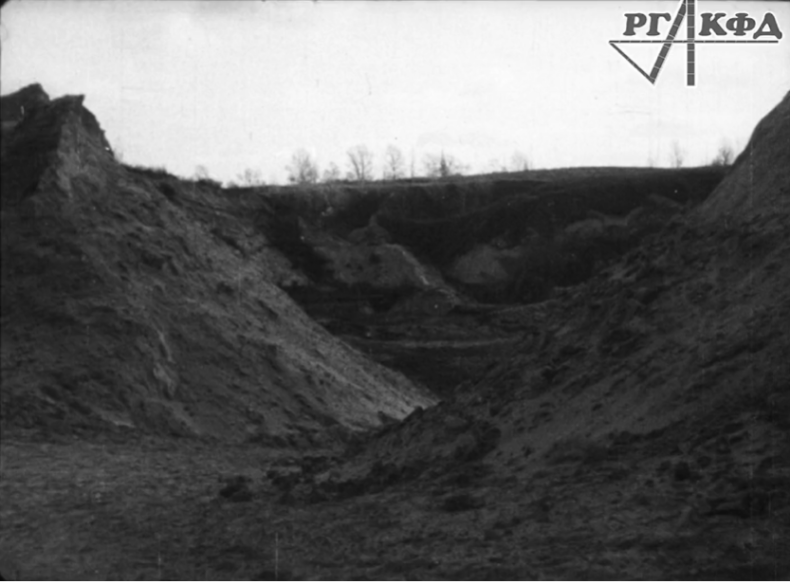

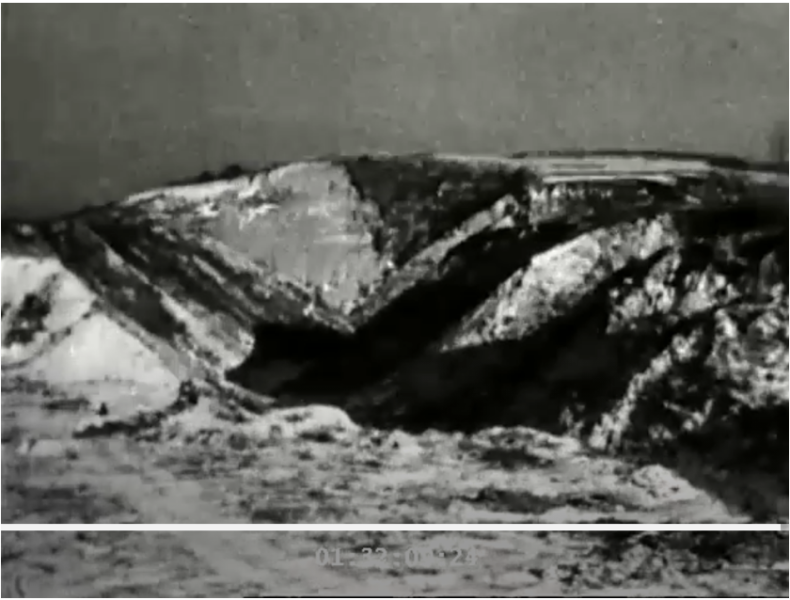

The long documentary FILM DOCUMENTS OF THE GERMAN FASCIST INVADERS’ ATROCITIES / KINODOKUMENTY O ZVERSTVAKH NEMETSKO-FASHISTSKIKH ZAKHVATCHIKOV was prepared in 1945 for the Nuremberg Tribunal of the Major War Criminals before the International Military Tribunal, where it was shown on February 19, 1946.13 It includes less than half a minute of footage of Babyn Yar, comprising two shots.14 By contrast with VICTORY IN RIGHT-BANK UKRAINE, it begins with a panning shot, which rapidly turns left and lasts ten seconds. During this rather dark shot, some distinctive patches of vegetation come into view. As we shall see in a moment when we turn to some unused footage, this suggests that the filming took place inside the sand quarry (see Figures 8–11).

Thanks to Dean’s research, the exact location and significance of the sand quarry is now clearer. It was close to the point where the two spurs mentioned above met. The Nazis made use of it on two occasions. In September 1941, it became what Dean calls the “antechamber of death” – the site where the Jews were forced to strip before being chased into the shooting area on the wide western spur. In August and September 1943, the Nazis then used the site to house selected prisoners in bunkers. These prisoners were forced to exhume and burn the corpses buried in the ravine.15

The ten seconds inside the quarry are followed by a five-second shot that slowly tilts downwards, revealing dead bodies. We can recognise this shot from VICTORY IN RIGHT-BANK UKRAINE, but here the beginning, with the visitors standing high above the site, is omitted. The footage continues with images of exhumed corpses in neat rows being observed by visitors, but these were almost certainly not filmed in the ravine but rather at the Syrets camp near Babyn Yar. The often chaotic way that the materials were archived and annotated does not help to resolve this question.16

Raw Footage from November 1943

Another piece of footage does not appear to have ended up in any documentaries or newsreels in the 1940s. As with all the Soviet footage recorded at Babyn Yar in late 1943, there is no original sound. Film scholar Irina Tcherneva has established that this footage was filmed by camera operator Grigorii Mogilevskii on November 22, 1943.17 It begins with a stationary shot lasting less than ten seconds (see Figure 12).

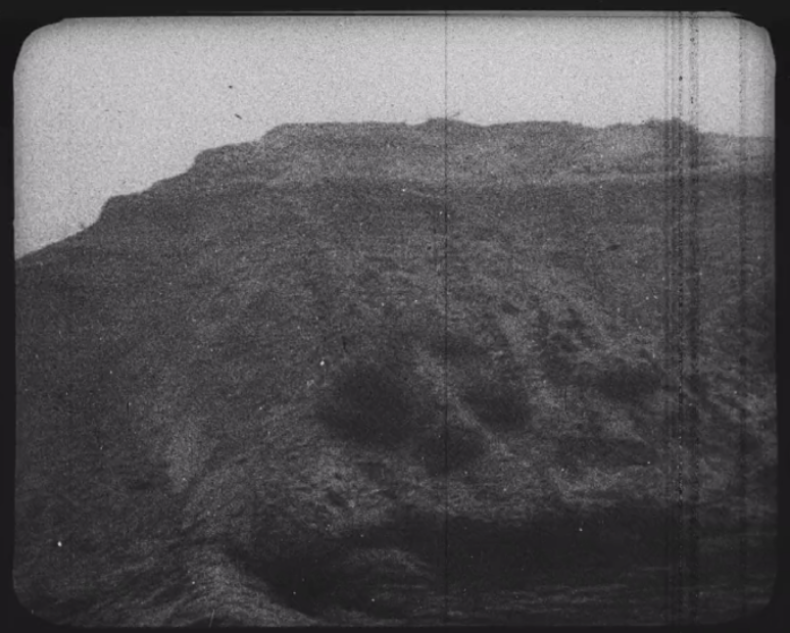

This is followed by an eleven-second pan from right to left, the third panning shot of Babyn Yar from this period that we know of. We get a clear view of the lone tree (on the left) and also of a large tree in the distance (on the right), which also appears in many photographs (see Figure 13; compare with Figures 1 and 2).

At the end of this pan, we see distinctive patches of vegetation on a steep wall (see Figure 14). As Dean has pointed out to me, the wide ‘Hähle’ spur to the west would not have been visible in a pan to the left from inside the narrow, long spur. We can therefore conclude that this pan probably ends with a view of the sand quarry. And because the patches of vegetation look like those shown at the beginning of the ten-second pan in FILM DOCUMENTS (Figure 8), this suggests that, as noted earlier, those ten seconds were filmed entirely from inside the quarry. The raw footage of the stationary shot (captured in Figure 12) was likely filmed there as well.

Following these shots in which no people appear, a group of visitors is shown for a few seconds standing down below on the base of the western spur. As in Hähle’s photograph, the lone tree is “hidden” by the trees behind it (see Figure 15; compare with Figure 2).

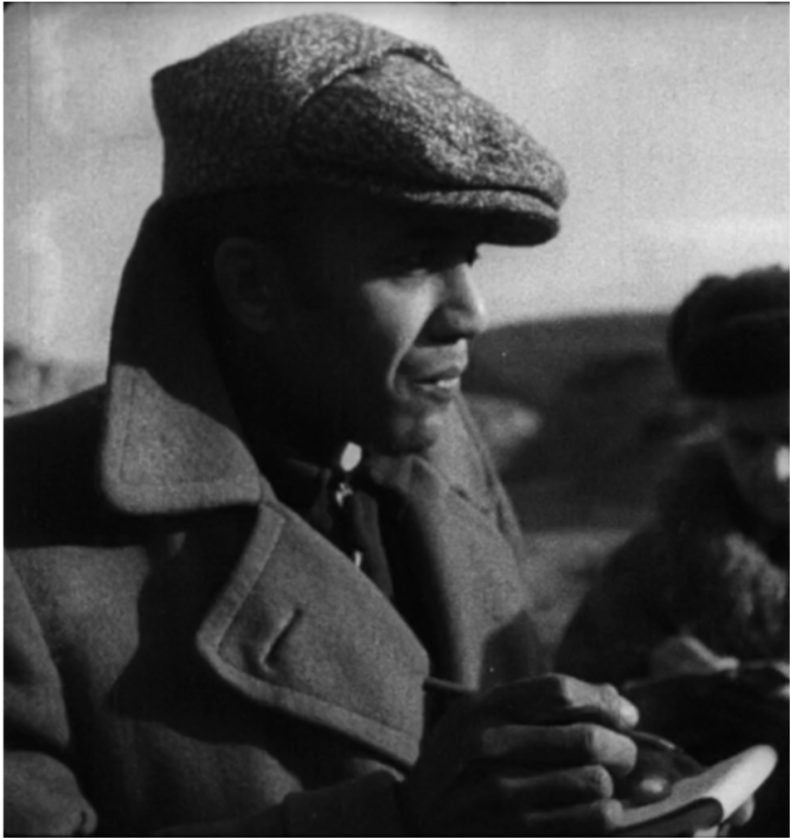

The visitors who appear in the shot were journalists and their entourage. They were being filmed during their second visit to the site on November 23, 1943. Though it has been neglected in previous research, this visit was a key moment in the global history of the Holocaust: at a time of intense scepticism about Soviet reports, journalists from abroad set foot for the first time on the site of a mass shooting of Jews. They were able to walk around, observe and touch human remains, take photographs and speak with locals – albeit under the watchful eyes of supervisors. Their first visit to the site took place the day before, on the date of their arrival in Kyiv. No survivors were brought to that first visit, but ahead of the second visit the journalists had requested to be able to speak with them.

In the footage, a civilian man with a cap, the survivor Vladimir Davydov (b. 1915), can be seen pointing at something. The conclusion of the shot strongly suggests that in that moment he and the group were standing on a slope of the long, narrow spur (see Figures 16 and 17).

During most of the filming, the group of visitors can be seen standing elsewhere, namely atop the wide western spur that is also visible in Hähle’s colour photograph. Although this is not absolutely clear from the footage (in which sometimes no horizon is visible), any lingering doubt is dispelled by a Soviet photograph taken on the same occasion, which shows (just as Figure 13 does from a different vantage point) both the lone tree and the large tree in the distance18 (see Figure 18).

There are also brief stationary shots of streets that the Jews were forced to march down on their way to Babyn Yar, including (probably) Dorohozhytska Street and Melnikova Street, and one of the gates of the Jewish Cemetery.19 These shots add to the cumulative weight of the other visual and textual sources documenting the route taken by the Jews.20

Babyn Yar Survivor Fima Vilkis (early 1944, with sound)

Efim (Fima) Abramovich Vilkis (b. 1910), a survivor of the Babyn Yar exhumation, can also be seen in the long-unused footage from November 1943. He was filmed at the site again, this time with sound, in February 1944 or slightly afterwards. Vilkis has sometimes been misidentified as Davydov, for instance in the first Soviet documentary to use this footage, the Russian-language BABYN YAR: THE LESSONS OF HISTORY / BABII IAR: UROKI ISTORII, which was broadcast on Soviet television in 1981.21 We know the man in the footage is Vilkis because of the original Russian caption to a photo portrait by Aleksei Ioselevich of him and two other survivors that was distributed to the visiting correspondents in 1943.22

One might gain the impression that this footage was filmed in November 1943, as Vilkis is wearing the same clothes (see Figure 19).

But this was not the case. The CINESOV project located the footage in the Russian archives and dated it to 1944.23 It is relevant to the spatial history of Babyn Yar.

Moreover: unless other materials are still hidden somewhere, Efim Vilkis appears to be the only person who survived Babyn Yar – or rather the only person known to have been in its vicinity while Kyiv was under Nazi rule (including all Kyivans and all perpetrators) – for whom we have any sound recording dating to the war years.24

This little-known survivor preferred to be called Fima rather than Efim. As records from the former NKVD archives reveal, he was born in Odessa in 1910, and before 1941 he used to live at 15 Gorkoho Street, Kyiv. He became known to the Soviet authorities of recaptured Kyiv at quite an early stage, on November 12, 1943, when he submitted a “statement” (zaiavlenie) to the NKVD. According to the statement, that same day he had “apprehended” on the street two men who had been prisoners of the Syrets camp near Babyn Yar and had been allowed to perpetrate sadistic beatings and random killings there. How Vilkis was able to arrest two people is unclear.25

At the time he met the correspondents, it would appear he had not been formally questioned. That happened on November 28 and December 2.26 According to the records of his questioning, he was a Jewish worker with seven years of education, was not a member of the Communist Party and had lived in Kyiv before 1941. Moreover, he had family there but did not know their whereabouts. He said he became a POW in the Poltava region on September 30, 1941 and described how as a prisoner at the Syrets camp, he narrowly escaped being buried alive in April 1943. He originally claimed that he had been a prisoner there since October 2, 1941. But that is not possible, since the camp did not yet exist at that point. He revealed more in the questioning on December 2: he had arrived at the camp (with three others) “from 48 Melnikova Street, where I worked as a prisoner at the police school.” The police school was a barracks housing German, ethnic German and Ukrainian camp guards, located very close to Babyn Yar.27 Vilkis said (and other survivors corroborated this claim) that he was among those who managed to escape from Babyn Yar in the early hours of September 29, 1943.

He was filmed with sound at Solntseva’s request. As the CINESOV project discovered, in a note from early February 1944 Solntseva sought to strengthen the case for making sound recordings of individuals like Vilkis by arguing that “the Americans who visited Babyn Yar [in November 1943] were stunned by the spectacle, but they said, ‘You can’t write about this in our newspapers. It’s so beyond human understanding that even if we wrote about it, no one would believe us.’”28 This still does not explain why only sound recordings of Vilkis exist. (Meanwhile, Soviet publications for internal consumption from the 1940s appear to have been silent about him, probably in part because Vilkis was the subject of an ongoing investigation.) We do not know what kind of instructions he received. The stilted language and phrases such as “our Soviet Kyiv” show that at the very least he was strongly influenced by Soviet officialese.

Talking in Russian to the camera, Vilkis says, as he had done when questioned in late 1943, that “in all, during our work here, we were forced to burn about 100,000 Soviet citizens.”

The speaker is standing on the left edge of the spur shown in the “Hähle” photograph. Stretching his arm towards it, Vilkis provides important spatial evidence when he says that the bodies were exhumed and burned right there:

Here in this area which in Kyiv is called Babyn Yar, we, prisoners of war who were captured by the Germans in 1941, were forced by the German fascist Gestapo authorities under threat of being shot to dig up these corpses and to burn them on bonfires, on pyres, which the fascist monsters forced us to build ourselves. Here at Babyn Yar there was a stench, a sinister stink. We, working here, [...]29

He stops talking. Then another, longer recording was made, in which he says:

Here in this place, which in Kyiv is called Babyn Yar, we prisoners of war were forced by the fascist monsters, we who happened to be prisoners in 1941, to burn the corpses of our Soviet citizens of Kyiv, whom the German monsters had shot here during the two years of their occupation. Here at Babyn Yar there were pyres, there was stench and stink. We were forced to pull out and, under threat of execution, stack the corpses on the stove.

Here they brought people, naked women and children in soul-destroyers [dushegubki],30 who suffocated in a gas van. All in all, during the time we worked here we were forced to burn about 100,000 Soviet citizens.

The Germans wanted to hide their – the traces of their crimes, and wanted to destroy us too after the end of our work. But they did not succeed. Of the three hundred people who worked here, twelve managed to escape. We escaped and so we will tell the whole world and our homeland about the barbarities that the fascist bastards committed in our native Kyiv.31

Little else is known of what happened to Vilkis after November 1943. Yad Vashem’s Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names contains relevant information and forms (list svidetelskikh pokazanii).32 A Kyivan, Liudmila Gart, who identified herself as a relative of “Efim Naumovich Vilkes,” testified in 1995 that he was born in 1914 and was married to “Sara Abramovna Vilkes,” who was murdered at Babyn Yar in 1941 together their son Abram (born in 1937). A second Kyivan named Zakhar Ostrovskii, who described himself as Vilkes’s “neighbour,” wrote in 2007 that “Efim Vilkes” was born in 1915 and worked at the rail station. His wife Sara and their only child, Abram (born in 1937), both died in the “punitive action” (karatel’naia aktsiia, a typical Soviet term for a massacre) of September 1941. According to Gart, Vilkis “perished at the front while fighting the fascists” in 1943. Ostrovskii says that he died in 1944, without adding details.

The family of three also appears in the list of names prepared by the Jewish Council of Ukraine, with a more precise home address (51 Gorkoho Street, apt. 3) but with the name misspelled as Vilkes.33 The Russian-language Memory Book of Ukraine, an online database, lists Vilkis as a native of Odessa who was born in 1910, and says he “perished in June 1944” while serving in the Red Army.34 But Soviet materials published on the Russian Ministry of Defence’s website Memory of the People do not confirm this: Vilkis appears only in a document dated June 4, 1944, a list of “former Red Army servicemen who escaped from enemy imprisonment and encirclement and have been sent by the 38th Army’s sanitary assembly point to various units.” According to this document, Fima Abramovich Vilkis, born in Odessa in 1910, was recruited in Kyiv’s Kahanovytskyi district as a lieutenant. Before that, he had commanded a rifle corps of the 97th Rifle Division. No information about his death is given.35 In conclusion, where and when Vilkis died is unknown. He must be considered missing in action.

The priceless audiovisual recording is all the more remarkable given that both Solntseva and Dovzhenko often expressed extreme hostility towards Jews during the war. This antisemitism went quite far, as revealed by Dovzhenko’s diary and, in particular, by recently published surveillance records from NKVD informers. For example, the informant and painter Mykola Hlushchenko, known abroad as Nicolas Gloutchenko, once (on December 9, 1943, according to his recollection) mentioned to the couple that the Germans had exterminated the Jews. They responded that they were pleased; after all, the Jews were dangerous enemies. Dovzhenko also expressed his approval of Hitler’s murder of Ukraine’s Jews in conversations with other people.36

Having discussed all the footage from 1943 and the Vilkis recording from 1944, we shall now turn to an entirely different kind of material: scenes with actors that were included in a film shown in Soviet cinemas for a few weeks in October and November 1945.

Footage from October 1944 Included in the Film THE UNVANQUISHED (1945)

On November 2, 1944, the press agency TASS reported the production of the first film by Kyiv Studios since the city’s liberation from the Germans. The footage had already been edited and the plan was to have the film ready before Red Army Day on February 23, 1945:

In recent days two mass film shoots took place: of the scene of the execution of the peaceful population in Babyn Yar and the meeting of two processions – a group of elderly people headed by Taras, going to the burial of their comrade who was killed by the Germans, and a group of peaceful inhabitants, being taken to their execution.

Several thousand people took part in the filming. The site in Babyn Yar and the streets next to the film studio at the Brest–Litovsk Highway, where some footage was also recorded, overflowed with people. Kyivans who had witnessed the bloody massacre by the Germans gave the director several valuable suggestions.37

This means that the filming took place in late October and perhaps also on November 1, 1944. It seems incredible that a mass shooting was reenacted in the same ravine where it had actually taken place just a few years earlier, but other sources confirm it. The British film scholar Jeremy Hicks obtained a photograph of the filming process from the personal archive of the director’s assistant, Emma Malaia. The site would be difficult to geolocate today, but the background looks like one of the slopes of Babyn Yar.38 No one appears to have expressed any concern about reenacting the massacre there.

THE UNVANQUISHED / NEPOKORËNNYE was the first fiction film anywhere in the world to show a procession of Jews being led away to be massacred in what today is often called the “Holocaust by bullets.” It premiered in Moscow in October 1945. That same month, director Mark Donskoi (or Donskoy, 1901–1981) wrote the following in Cinema Chronicle, a publication by the USSR Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries:

When we were filming the scene showing the shooting of Jews at Babyi-Yar we received consultation on this scene from people who had miraculously lived through this butchery, people who had been shot down on this very spot. They had been wounded and in the dead of night, they had crawled out from under the mounds of dead bodies among which were their own kith and kin. They escaped alive, and these witnesses of the monstrous nazi [sic] atrocities now helped us to reproduce the appalling truth for the annals of history.

Leah Gershman is not a fictitious person. Leah Gershman was one of those who lived through experiences that no words can describe. These people not only helped us to re-create this ghastly scene in all its truth and fearsomeness, they also fired our emotions.39

Nevertheless, it is not clear whether Donskoi, a Jew from Odessa, actually intended to realistically reproduce the Babyn Yar massacre. Evidently inspired by the Odessa Steps sequence in Sergei Eisenstein’s BATTLESHIP POTEMKIN / BRONENOSETS POTEMKIN (1925), the killers are depicted as a line of advancing soldiers. The Jews they shoot are standing on the same level and facing them. Unlike the reality of Babyn Yar in September 1941, Donskoi’s film has Jews wearing armbands and not forced to undress, while the guards are in the uniforms of the Ukrainian police. It is very unlikely that any of the Kyivans Donskoi spoke to would have described the massacre in this way.

In the short Babyn Yar segment, the images of murder alternate with shots of dark clouds (accompanied by loud music). There is around half a minute of footage that is relevant to the site’s spatial history; it is interspersed with close-ups of individuals that were possibly not filmed at the same location and do not show the surrounding space. The relevant footage comprises one long shot and six short ones lasting twenty-seven seconds in total. In the longer shot, the camera follows an actor playing a uniformed German as he walks from left to right. Behind him we can see a section of a brightly lit, sharply descending slope with a horizontal strip of vegetation. It seems to be the left (northern) side of the western spur that we are familiar with from Hähle’s photograph (see Figure 20).

The camera then tilts to an elevation from which other people are observing something further to the right (see Figure 21). It later turns out they are looking down at the site where the massacre is about to begin. The elevated spot may be on or near to what several German witnesses referred to as “Generals’ Hill,” a high vantage point from which the organisers of the massacre could issue orders or simply watch.40

As the camera moves to the right and downwards, a building comes into view that is not visible in ground photographs and was not previously known41 (see Figure 22).

The shot ends with a view of an area of level ground filled with people (see Figure 23).

Where this was filmed is not clear; one possibility is that it was on the long, narrow spur. The shot is followed by three close-ups of actors, which do not contain any spatial information, intermixed with more panorama shots.

A Visit by UN Representatives, August 1946

The final footage I shall discuss here is an unpublished segment showing people walking to the edges of Babyn Yar, which appears between footage of a drive through Kyiv and footage of a plane taking off. I was able to study this segment in 2013 thanks to the CINESOV project, which located it in the Russian film archives under the title “Arrival of La Guardia in the City of Kyiv (1946).”42 The subject of the footage is Fiorello La Guardia (1882–1947), a former mayor of New York who at that time was Director General of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, which also had a small office in Kyiv. La Guardia held this position for nine months up until December 1946. According to the UN archives, La Guardia arrived by plane from Moscow on August 26, 1946, met Soviet dignitaries and, “in a tour of Kiev and its environs […,] visited the famous Lavra Monastery, the Kiev-Pechersky Monastery, the grave of Soviet war hero General Vatutin and other historic spots.”43 Notably, the visit to Babyn Yar is not mentioned. The few Americans who accompanied La Guardia have not shared any recollections of the visit.

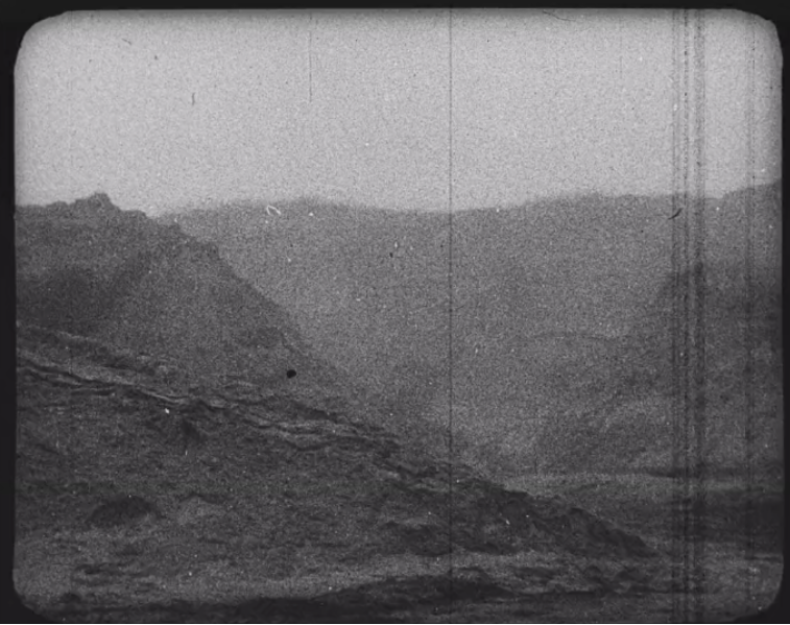

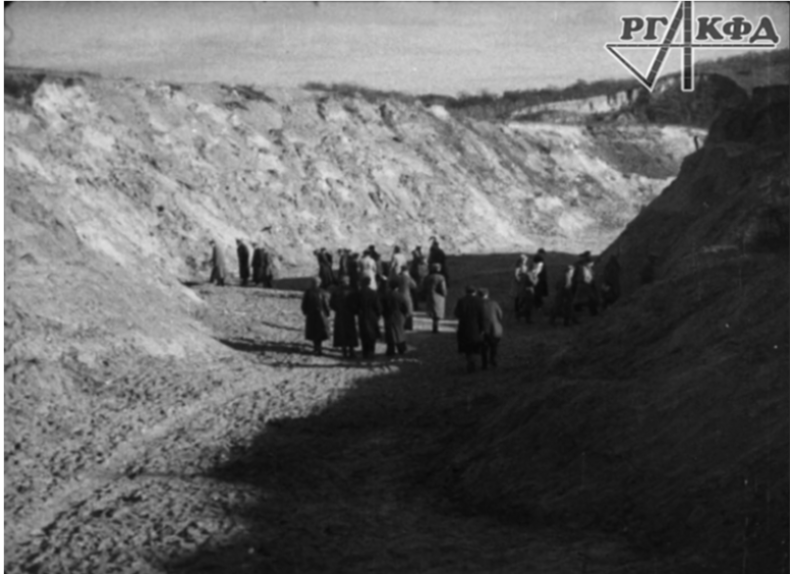

The footage at Babyn Yar, also employed by Dean, consists of three panning shots lasting a total of seventeen seconds.

It first shows the wider area, including the approaches to the ravine, and we can see the large tree on the right in the distance as well as the by now familiar lone tree on the ravine edge (in the centre) (see Figure 24).

The lone tree is still visible in the final shots. Based on other sources, we can conclude (in agreement with Dean) that the end of this footage shows the long, narrow spur and, notably, the sand quarry on the left (see Figure 25). Also on the left, we can see houses on the northern horizon; further research is needed to determine their identity. It should be emphasised that this particular footage mostly leaves out the western “Hähle” spur, the main site of the massacre.

Individuals on Film

Many of the individuals shown in the various pieces of footage discussed above have not yet been identified by name. In VICTORY IN RIGHT-BANK UKRAINE, this applies to the members of the ChGK delegation. In the footage with the correspondents, a tall, grim-looking Soviet man is always standing close to the speakers; he also appears in films from other Kyiv sites and may have been an NKVD official. Mykola Bazhan (1904–1983), deputy chair of the government of Soviet Ukraine, can be recognised in the crowd.

The group of visitors in November 1943 included eight American and five British newspaper correspondents, all male. The camera rests for a moment on the Americans William (Bill) H. Lawrence (on the left) and David Nichol, who worked for, respectively, the New York Times and the Chicago Daily News.44 Possibly visible in that same moment is the Ukrainian architect Pavel Aleshin (1881–1961), who acted as the foreigners’ informal guide45 (see Figure 26).

Another recognisable figure is Homer Smith (1909–1972), a journalist who, notably, was the first African American ever to set foot in Babyn Yar (see Figures 27–28). Having lived in the Soviet Union since 1932 and become a Soviet citizen, Smith’s official non-Soviet affiliation was with the Associated Negro Press. His published memoirs contain just one sentence about Babyn Yar, which does not make clear that he had been there.46 I was alerted to his presence at the site by a report in a wartime Soviet Ukrainian newspaper. His name is also mentioned in caption sheets.47

The footage with people is also of interest because of the way the visitors conduct themselves. One former prisoner bares his leg to show the correspondents the wounds from his shackles. In the footage with La Guardia, who had a Jewish mother (a fact he preferred not to emphasise), there is no solemnity at all, at least until the visitors reach the edge of the ravine. La Guardia is smoking, walking at a brisk pace and seemingly engaged in conversation.

Conclusion

This article has not been able to answer all the questions that the footage raises. It remains unclear how the spatial footage relates to the work of Soviet investigators (the NKVD and ChGK). Perhaps it was unclear at the time as well. Experts who specialise in Soviet footage of atrocity crimes have found a pattern of haziness about the intended audience of the filming.48 In the specific case of Babyn Yar, some oddities merit closer attention. As we saw, some of the key footage of the murder site, including clips with sound of a survivor addressing “the whole world and our homeland,” was filmed at the instigation of film directors who regarded Jews as enemies and said in private conversations at the time that they were pleased that the Germans had exterminated them. Conversely, a Jewish film director had a massacre of Jews reenacted at the very ravine where that mass murder had actually taken place only three years earlier. It is possible that outtakes from that film still exist somewhere.

It was also possible to make two more discoveries. Four seconds of historical footage that was included in the Soviet documentary mentioned above, BABYN YAR. THE LESSIONS OF HISTORY, could have been filmed in November 1943. For three seconds, we see the western spur filmed from the northern side. The origin of this footage still requires further research49 (Figure 29).

I recently discovered that two panning shots of the ravine spur known from the lone tree photographs, which last just over half a minute, appear in Vladimir Dvinskii’s little-known documentary film PEACE BE WITH YOU, SHOLOM! / MIR VAM, SHOLOM!, released in 1989.50 The footage looks old, but its date and provenance are unclear.

It has been possible to provide some definite answers, however. We can conclude that the western spur, the main site of the massacre seen in Hähle’s colour photograph in 1941, appeared in footage filmed in November 1943 and early 1944, and possibly in footage from October/November 1944. We can also conclude that only a small part of that spur was captured on film in 1946 when representatives of the United Nations visited the site. It also turned out that there exists more footage of the sand quarry than just the few seconds filmed from a distance in 1946, and that this material was captured by a camera operator who was standing inside the quarry. Finally, I have increased clarity by excluding adjacent footage that could be very easily misattributed to Babyn Yar. More studies should be carried out to investigate footage from Kyiv (for instance, of the Syrets camp) through a spatial history lens. Hopefully, the findings presented here will provide a basis for further research on this challenging and socially relevant topic.

- 1

Martin [C.] Dean, “Explaining the Location of the Mass Shootings at Babyn Yar on September 29–30, 1941,” Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, dated September 28, 2020, published June 30, 2021, https://ukrainianjewishencounter.org/en/explaining-the-location-of-the-…; Martin C. Dean, Investigating Babyn Yar: Shadows from the Valley of Death (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2024).

- 2

Source: Tsentral’nyi derzhavnyi audiovizual’nyi ta elektronnyi arkhiv (Kyiv), odynytsia zberihannia 0-004243, https://avd.archives.gov.ua/files/foto-doc.php?name=109369. A slightly cropped version is available at Babyn Iar: Liudyna, vlada, istoriia. Dokumenty i materialy. Elektronne vydannia, ed. V. Nakhamanovych, http://history.kby.kiev.ua/publication/illu_b48.html.

- 3

Archiv des Hamburger Instituts für Sozialforschung, Bild 008,015 (PK-Fotograf Johannes Hähle). The image can be found online at https://history.kby.kiev.ua/publication/illu_b15.html.

- 4

Dean, Investigating Babyn Yar, 36–37, 153. Dean speaks either of two separate ravines or, elsewhere, of the main ravine and the western spur. Historical documents and scholarly publications have tended to speak of a single ravine with multiple spurs (Rus. otrogy; Ukr. vidrohy).

- 5

The list includes Marie Moutier-Bitan, Sophie Nagiscarde, Valérie Pozner, Alexandre Sumpf, Irina Tcherneva, and Vanessa Voisin.

- 6

Aleksandr Dovzhenko, Dnevnikovye zapisi 1939–1956, Shchodennykovi zapysy 1938–1956 (Kharkiv: Folio, 2013), 265.

- 7

Vanessa Voisin, “De la paix à la guerre, de la fiction au documentaire: Alexandre Dovjenko et Youlia Solntseva,” Conserveries mémorielles: Revue transdisciplinaire 24 (2020): 18.

- 8

It is important not to mistake other scenes for Babyn Yar, such as the vivid images of German POWs exhuming corpses at the former camp of Darnytsia.

- 9

Jeremy Hicks, First Films of the Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 1939–1946 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012), 130.

- 10

In a version available online at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u8nBwmW_8rQ, the footage begins at 13:50.

- 11

The conduct of Operation 1005 in Kyiv is described in Andrej Angrick, “Aktion 1005”: Spurenbeseitigung von NS-Massenverbrechen 1942–1945: Eine “geheime Reichssache” im Spannungsfeld von Kriegswende und Propaganda, vol. 1 (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2018), 346–399.

- 12

Gosudarstvennyi arkhiv Rossiiskoi Federatsii (GARF), f. 7021, op. 128, d. 200, l. 21 (“tela evreev, zhitelei Kieva, rasstreliannykh v ovrage ‘Babii Iar’,” available online at http://victory.rusarchives.ru/index.php?p=31&photo_id=789. A cautious approach is needed. For instance, due to a Soviet cataloguing error, an image of the long death pit Drobytskyi Yar near Kharkiv is usually misattributed to Babyn Yar; one example can be seen in David Shneer, “Ghostly Landscapes: Soviet Liberators Photograph the Holocaust,” Humanity 5, no. 2 (Summer 2014): 245. A scan of the image can be found at https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/photos/61981 (Yad Vashem Archival Signature 3521/129). This same pit is seen in Dovzhenko’s film BITVA ZA NASHU SOVETSKUIU UKRAINU / THE BATTLE FOR OUR SOVIET UKRAINE / UKRAINE IN FLAMES (released in October 1943); for discussion see Hicks, First Films of the Holocaust, 118–119.

- 13

On the documentary, see Hicks, First Films of the Holocaust, 186–195. The CINESOV team discovered that the documentary was prepared in haste to be ready in time for the tribunal.

- 14

The film is filed in the Russian State Archive of Film and Photographic Documents (RGAKFD) in Krasnogorsk under the slightly different title OTOMSTIM! KINODOKUMENTY O CHUDOVISHCHNYKH ZLODEIANIIAKH I NASILIIAKH NEMETSKO-FASHISTSKIKH ZAKHVATCHIKOV, reel 4, shots 18–19, https://www.vhh-mmsi.eu/mmsi/objects/45308/summary (shots 20 and 21 seem to be the Syrets camp). The footage is available online under the title SOVIET FILM OF ATROCITIES SHOWN AT NUREMBERG TRIALS, reel 4, 1:31, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn616417.

- 15

See Dean, Investigating Babyn Yar, 11, 47–52, 55–63, 107–108, 110, 112, 115–124.

- 16

Information received from Irina Tcherneva.

- 17

THE CITY OF KYIV / GOROD KIEV (1943), from RGAKFD 8591, reel 7, shots 2–15, https://www.vhh-mmsi.eu/mmsi/objects/61316/summary/media/13842. The original is held in RGAKFD as items 5204 and 2593. The footage with the foreign correspondents is also held in the Tsentral’nyi derzhavnyi audiovizual’nyi ta elektronnyi arkhiv in Kyiv, as Zbirnyk kinosiuzhetiv no. 2593.

- 18

Taken by Kazimir Lishko, reproduced from Dmytro Malakov, Kyïv: 1939–1945: Post scriptum, 2nd rev. ed. (Kyiv: Varto, 2010), 187. At present, there is only one known photograph taken on this occasion by any of the foreign correspondents (specifically, by the correspondent for the Associated Press). See Eddy Gilmore, “Liberated Ukraine,” National Geographic Magazine 85, no. 5 (May 1944): 521; also reproduced in Dmytro Malakov, Kyïv 1939–1945: Fotoal’bom (Kyiv: Vydavnytstvo ‘Kyi’, 2005), 394.

- 19

GOROD KIEV (1943), from RGAKFD 8591, reel 12, shots 3–11, https://www.vhh-mmsi.eu/mmsi/objects/61317/summary. Some of this footage appears in BABI YAR: CONTEXT (Sergei Loznitsa, 2021), from 1:12:58. As well as showing fourteen photographs by Johannes Hähle, Loznitsa’s film depicts the ravine with the following footage from the 1940s: the visiting correspondents, with imagined spoken words by survivor Vladimir Davydov and the female interpreter (at 1:13:20–1:14:11); the stationary shot captured above in Figure 12 (at 1:14:12–1:14:20); and a compilation of the two recordings of survivor Efim Vilkis, who is not identified by name (at 1:14:21–1:15:40). I discuss Vilkis below. I cannot explain why in Loznitsa’s film the audio of Vilkis’s first sentence replaces the original Russian word my (we) with tut (here). That produces the following result: “Вот здесь на этой площади, которая называется в Киеве Бабьим Яром, здесь вот, среди этого, тут, военнопленные …” The film ends with footage of Babyn Yar presumably from the 1960s (at 1:55:04–1:58:48).

- 20

For a recent account of Dorohozhytska Street’s place in the history of the massacre, see Dean, Investigating Babyn Yar, 83–91.

- 21

On this documentary, see Karel C. Berkhoff, “Babyn Yar in Cinema,” in Babyn Yar: History and Memory, ed. Vladyslav Hrynevych and Paul Robert Magocsi (Toronto: University of Toronto Chair of Ukrainian Studies, 2023), 327–350.

- 22

“1943: The Babyn Yar Massacres,” July 3, 2023, https://www.billdownscbs.com/2013/07/blood-at-babii-yar-kievs-atrocity-story.html, accessed January 16, 2024. When the same portrait was published by the Soviet embassy in the US, Vilkis was again precisely identified. “Only Three Survived …” USSR Information Bulletin 4, no. 11 (January 27, 1944): 1. In 1945, the American magazine Collier’s even carried a story about his life that was illustrated with a drawing of him by William Auerbach-Levy, which was evidently based on the same photograph. See George Creel, “The Heroes: Yefim Vilkis,” Collier’s, May 15, 1945, 38.

- 23

Valérie Pozner et al., eds, Filmer la Guerre 1941–1946: Les Sovíetiques face à la Shoah (Paris: Mémorial de la Shoah, 2015), [42]–43. The footage is titled THE POW CAMP IN DARNYTSIA; BABYN YAR / LAGER’ VOENNOPLENNYKH V DARNITSE; BABII IAR (1943), RGAKFD 9119, reel 1, shots 17 and 18, https://www.vhh-mmsi.eu/mmsi/objects/47507/summary. The camera operator is unknown.

- 24

This does not mean that the search for sound recordings relating to Babyn Yar should stop. A. M. Spasskii (b. 1910) was a radio technician for Radiofilm during the war. Afterwards, he headed All-Union Radio’s sound recording department. Writing in 1982, he recalled that “after the liberation of Kyiv our group made recordings for the commission that investigated the circumstances of the demise of thousands of people at Babyn Yar. We recorded the stories of some survivors of the massacre, the reports and conclusions of the experts who carried out the exhumations and also imprisoned German soldiers who had participated in that beastly execution.” To date, no attempt appears to have been made to find out what happened to these recordings. Boris Spasskii, “Po dorogam voiny: Zapiski frontovogo zvukooperatora,” in Radio v dni voiny: Ocherki i vospominaniia vidnykh voenachal’nikov, izvestnykh pisatelei, zhurnalistov, deiatelei iskusstva, diktorov radioveshchaniia, ed. M. S. Gleizer and N. M. Potapov, 2nd exp. and rev. ed. (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1982), 167–168; biographical information from T. M. Goriaeva, ed., Istoriia sovetskoi radiozhurnalistiki: Dokumenty. Teksty. Vospominaniia 1917–1945 (Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Moskovskogo universiteta, 1991), 415.

- 25

Tatiana Evstafieva and Vitalii Nakhmanovich, eds, Babii Iar: Chelovek, vlast’, istoriia, vol. 1: Istoricheskaia topografiia: Khronologiia sobytii (Kyiv: Vneshtorgizdat Ukrainy, 2004), 328–329; see also http://history.kby.kiev.ua/publication/doc_66.Zayava_v_NKVS_kolishnogo_v’yaznya_Siretskogo_kontstaboru_F._Vilkisa.html.

- 26

A transcript of the first round of questioning can be found in Evstafieva and Nakhmanovich, Babii Iar, 340–341; see also http://history.kby.kiev.ua/publication/doc_72.Z_protokolu_dopitu.... The text of the questioning on 2 December 1943 is available at http://history.kby.kiev.ua/publication/doc_2164.html#Vilkis.

- 27

For details, see Dean, Investigating Babyn Yar, 199–201.

- 28

Pozner, Filmer la Guerre 1941–1946, 42.

- 29

In the original Russian: “Вот здесь на этой площади, которая называется в Киеве Бабьим Яром, здесь вот, среди этого, мы, военнопленные, которые попали в сорок первом году в немецкий плен, под угрозой расстрела заставлялись немецкими фашисткими органами Гестапо раскапывать эти трупы, и сжигать их на кострах, на печах, которые фашистские изверги заставляли нас самих строить. Здесь на этом Бабьем Яру стоял смрад, стоял зловещий вонь. Мы, работая здесь, [...].”

- 30

“Soul-destroyers” [dushegubki] during and after war in the Soviet Union became a common way of referring to Nazi gas vans.

- 31

This segment, except for the final sentence, is also available in open access on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website: RG-60.3150 (film ID: 2489), BABI YAR (from 00:29), https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1002639; and at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xweszTTL-Ow#action=share. In the original: “Вот здесь в этом месте, которая называется в Киеве Бабий Яр, нас военнопленных заставили фашистские изверги, которые [sic] мы случайно в тысяч девятсот сорок первом году попали в плен, сжигать трупы наших киевских советских граждан, которых немецкие изверги за два года своей оккупации здесь расстреляли. Здесь вот в этом Бабьем Яру стояли печи, здесь стоял смрад и вонь. Нас заставляли вытаскивать и под огрозой расстрела складывать это трупы на печку.

Сюда же привозили в душегубках людей, голых женщин и детей, задушенных в газовой машине. Всего за время нашей работы здесь нас заставили сжечь около ста тысяч советских граждан.

Немцы хотели скрыть своих - следы своих преступлений, и хотели после окончании работы тоже нас уничтожить. Но это им не удалось. Из трехсот человек, которые здесь работали, двенадцати человек удалось спастись. Мы совершили побег и этим самим расскажем всему миру и нашей родине о тех варварствах, которые производили фашистские гады в нашем родимом Киеве.”

- 32

Yad Vashem, The Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names, https://yvng.yadvashem.org/.

- 33

Il’ia Levitas, ed., Babii Iar: Kniga pamiati (Kyiv: Izdatel’stvo “Stal’”, 2005), 92.

- 34

Kniga pamiati Ukrainy: Elektronnaia baza dannykh 1941–1945, https://memory-book.ua/search?s=%....

- 35

Pamiat’ naroda 1941–1945, https://pamyat-naroda.ru/heroes/.

- 36

Iurii Shapoval, Neproshchenyi: Oleksandr Dovzhenko i komunistychni spetssluzhby (Warsaw, Kyiv and Kharkiv: Instytut politychnykh i etnonatsional’nykh doslidzhen’ im. I.F. Kurasa NAN Ukraïny and Instytut Studiów Politycznych PAN, 2022), 198–200; Pavel Polian, Babii Iar: Reflektsiia (Moscow: Izdatel’skii Dom “Zebra E,” 2022), 527. On Hlushchenko, see also the exhibition published online in 2021: https://art.cdvr.org.ua/?hlushchenko.

- 37

TASS, “S’ëmki fil’ma ‘Nepokorënnye’,” Trud, November 2, 1944, 2.

- 38

Reproduced in Hicks, First Films of the Holocaust, 143.

- 39

For details on the film, see Berkhoff, “Babyn Yar in Cinema,” 329–334, which is partly based on Olga Gershenson, The Phantom Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and Jewish Catastrophe (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2013), 40–56; and Hicks, First Films of the Holocaust, 134–156 (the quotation from Cinema Chronicle can be found on p. 142).

- 40

Dean, Investigating Babyn Yar, 149–150.

- 41

When informed by me of this quandary, Dean again studied the German aerial photograph taken on September 26, 1943. He said that he has now noticed, on the right-hand edge of the sand quarry, close to the drop into the long, narrow spur and near the entrance, a spot that may be the shadow of a building.

- 42

PRIEZD LA GARDIIA V G. KIEV (1946) / ARRIVAL OF LA GUARDIA IN KYIV (1946), RGAKFD 6515-1, shots 1–6, https://www.vhh-mmsi.eu/mmsi/objects/61311/summary/media/13837.

- 43

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, “Resolutions on Policy: Fifth Session of the Council,” typescript (1946), https://search.archives.un.org/uploads/r/united-nations-archives/9/2/0/….

- 44

Handwritten caption sheets by the camera operator, obtained by Irina Tcherneva, date the footage to November 22, 1943, and identify Lawrence and Nichol.

- 45

Malakov, Kyïv: 1939–1945: Post scriptum, 186, identifies him in Kazimir Lishko’s photograph based on a dark fur hat, but the person in the hat lacks the “long, flowing mustache” which the American Associated Press correspondent described him as having; see Eddie [sic; Eddy] Gilmore, “Writer Visits Spot Where Nazis Put Thousands of Jews to Death,” The State Journal, November 30, 1943, 3.

- 46

He recalled that upon meeting a Jewish man in Lublin in the summer of 1944, “I gave him all the information I possessed, including the slaughter of the Jews in Kiev when the Germans captured that Ukrainian city, with its large Jewish population.” Homer Smith, Black Man in Red Russia: A Memoir (Chicago: Johnson Publishing Company, 1964), 194. Compare with the portrait of Smith taken on his arrival in the Soviet Union in 1932: Malik Simba, “Homer Smith, Jr. (1909–1972),” BlackPast, January 14, 2018, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/smith-homer-jr-1909-….

- 47

“Kiev – v serdtsakh vsekh tsivilizovannykh liudei mira,” Sovetskaia Ukraina, November 26, 1943, 4.

- 48

Vanessa Voisin, “Soviet Footage of War Crimes, 1941–1946: Between Propaganda and Judicial Evidence,” in Defeating Impunity: Attempts at International Justice in Europe since 1914, ed. Ornella Rovetta and Pieter Lagrou (New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2022), 164.

- 49

Screenshot made from the English version, BABI YAR. LESSONS OF HISTORY (Vitaly Korotych et al., Kyiv, [1983?], available at United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, RG-60.4200, film ID 2677, online at https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1002768, at 31:24-31:28.

- 50

The film is available online at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=05RCBH98yUo; the segment in question is at 0:43:35–0:44:10. Dvinskii was assisted by German director Irmgard von zur Mühlen.

Angrick, Andrej. “Aktion 1005.” Spurenbeseitigung von NS-Massenverbrechen 1942–1945. Eine „geheime Reichssache“ im Spannungsfeld von Kriegswende und Propaganda. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2018.

[Anonym]. “Kiev — v serdtsakh vsekh tsivilizovannykh liudei mira.” Sovetskaia Ukraina. November 26, 1943, 4.

[Anonym]. “Only Three Survived…” Information Bulletin, Embassy of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics IV, no. 11 (January 27, 1944): 1.

“1943. The Babyn Yar Massacres.” Bill Downs, War Correspondent. Published 2013. Updated January 27, 2024. https://www.billdownscbs.com/2013/07/blood-at-babii-yar-kievs-atrocity-story.html.

Berkhoff, Karel C. “Babyn Yar in Cinema.” In Babyn Yar: History and Memory, ed. V. Hrynevych and P .R. Magocsi, 327-350. Toronto: University of Toronto Chair of Ukrainian Studies, 2023.

Dean, Martin [C.]. “Explaining the location of the mass shootings at Babyn Yar on September 29–30, 1941.” Dated September 28, 2020, published on June 30, 2021. https://ukrainianjewishencounter.org/en/explaining-the-location-of-the-mass-shootings-at-babyn-yar-on-september-29-30-1941/.

Dean, Martin C. Investigating Babyn Yar: Shadows from the Valley of Death. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2024.

Dovzhenko, Aleksandr. Dnevnikovye zapisi 1939–1956, Shchodennykovi zapysy 1938–1956. Kharkiv: Folio, 2013.

Creel, George. “The Heroes. Yefim Vilkis.” Collier’s, May 15, 1945, 38.

Evstafieva, Tatiana, Vitalii Nakhmanovich, eds. Babii Iar: Chelovek, vlast’, istoriia. Kniga 1: Istoricheskaia topografiia. Khronologiia sobytii. Kyiv: Vneshtorgizdat Ukrainy, 2004.

Gershenson, Olga. The Phantom Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and Jewish Catastrophe. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2013.

Gilmore, Eddie [sic; Eddy]. “Writer Visits Spot Where Nazis Put Thousands of Jews to Death.” The State Journal, November 30, 1943, 3.

Gilmore, Eddy. “Liberated Ukraine.” The National Geographic Magazine 85, no. 5 (May 1944): 513–536.

Goriaeva, T.M. , ed. Istoriia sovetskoi radiozhurnalistiki: Dokumenty. Teksty. Vospominaniia 1917–1945. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Moskovskogo universiteta, 1991.

Hicks, Jeremy. First Films of the Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 1939–1946. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012.

Levitas, Il’ia, ed. Babii Iar: Kniga pamiati. Kyiv: Izdatel’stvo “Stal’,” 2005.

Malakov, Dmytro. Kyïv 1939–1945. Fotoal’bom. Kyiv: Vydavnytstvo “Kyi,” 2005.

Malakov, Dmytro. Kyïv. 1939–1945: Post scriptum, 2nd rev. ed. Kyiv: Varto, 2010.

Polian, Pavel. Babii Iar. Reflektsiia. Moscow: Izdatel’skii Dom “Zebra E,” 2022.

Pozner, Valérie et al., eds. Filmer la Guerre 1941–1946. Les Soviétiques face à la Shoah. Paris: Mémorial de la Shoah, 2015.

Shapoval, Iurii. Neproshchenyi. Oleksandr Dovzhenko i komunistychni spetssluzhby. Warsaw, Kyiv, and Kharkiv: Instytut politychnykh i etnonatsional’nykh doslidzhen’ im. I.F. Kurasa NAN Ukraïny; Instytut Studiów Politycznych PAN, 2022.

Shneer, David. “Ghostly Landscapes: Soviet Liberators Photograph the Holocaust.” Humanity 5, no. 2 (Summer 2014): 235-246.

Simba, Malik. “Homer Smith, Jr. (1909-1972).” January 14, 2018, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/smith-homer-jr-1909-1972/.

Smith, Homer. Black Man in Red Russia: A Memoir. Chicago: Johnson Publishing Company, 1964.

Spasskii, Boris. “Po dorogam voiny. Zapiski frontovogo zvukooperatora.” in Radio v dni voiny: Ocherki i vospominaniia vidnykh voenachal’nikov, izvestnykh pisatelei, zhurnalistov, deiatelei iskusstva, diktorov radioveshchaniia, 2nd, exp. and rev. ed. M. S. Gleizer and N. M. Potapov, 167–168. Moscow: “Iskusstvo,” 1982.

TASS. “S”ëmki fil’ma ‘Nepokorënnye.’” Trud, November 2, 1944, 2.

Voisin, Vanessa. “De la paix à la guerre, de la fiction au documentaire. Alexandre Dovjenko et Youlia Solntseva.” Conserveries mémorielles. Revue transdisciplinaire 24 (2020): 1-31.

Voisin, Vanessa. “Soviet Footage of War Crimes, 1941–1946: Between Propaganda and Judicial Evidence.” In Defeating Impunity: Attempts at International Justice in Europe since 1914, ed. Ornella Rovetta and Pieter Lagrou, 146-173. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2022.

Archival Sources

Archiv des Hamburger Instituts für Sozialforschung, Bild 008,015 (PK-Fotograf Johannnes Hähle)

Babyn Iar: Liudyna, vlada, istoriia. Dokumenty i materialy. Elektronne vydannia, ed. V. Nakhamanovych, http://history.kby.kiev.ua.

Gosudarstvennyi arkhiv Rossiiskoi Federatsii, f. 7021, op. 128, d. 200, l. 21, online at http://victory.rusarchives.ru/index.php?p=31&photo_id=789.

Kniga pamiati Ukrainy. Elektronnaia baza dannykh 1941–1945, https://memory-book.ua.

Pamiat’ naroda. https://pamyat-naroda.ru/heroes/.

Tsentral’nyi derzhavnyi audiovizual’nyi ta elektronnyi arkhiv (Kyiv), odynytsia zberihannia 0-004243, https://avd.archives.gov.ua/files/foto-doc.php?name=109369.

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, “Resolutions on Policy. Fifth Session of the Council,” typescript, Geneva, Switzerland, 1946, 18–19, UN archives, 124.5 Resolutions, https://search.archives.un.org/uploads/r/united-nations-archives/9/2/0/920f5b03df0c1a4fe4ed8e45c4dd60a0e238f32f0c7f172deff9d8572e695657/S-1301-0000-1247-00001.PDF.

Yad Vashem, The Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names, https://yvng.yadvashem.org/.