Reel Life: Memory and Gender in Soviet Estonian Home Movies and Amateur Films. A Case Study of the Estonian TV Series 8 MM LIFE (2014–2015)

Table of Contents

Liberated on Film: Images and Narratives of Camp Liberation in Historical Footage and Feature Films

Mexican Public Health History through Film: The Riches of a Film Archive, 1945–1970

Reel Life: Memory and Gender in Soviet Estonian Home Movies and Amateur Films. A Case Study of the Estonian TV Series 8 MM LIFE (2014–2015)

Film as Instrument of Social Enquiry: The British Documentary Film Movement of the 1930s

Visibility and Torture: On the Appropriation of Surveillance Footage in YOU DON’T LIKE THE TRUTH

Trapped in Amber: The New Materialities of Memory

Be Part of History: Documentary Film and Mass Participation in the Age of YouTube

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Jõhvik, Liis: Reel Life: Memory and Gender in Soviet Estonian Home Movies and Amateur Films. A Case Study of the Estonian TV Series 8 MM LIFE (2014–2015). In: Research in Film and History. Research, Debates and Projects 2.0 (2019), No. 2, pp. 1–10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14798.

Introduction

There is a global boom in personal accounts, autobiographies, and memoirs telling the stories of real individuals and their experiences, including first-person blogs, vlogs, videos, and other forms of online self-expression, as well as documentaries and television series. This phenomenon can in part be attributed to widening access to technology, but more abstract and philosophical causes have also contributed. The desire to be subjects of documentary can be seen as a reflection of the fragmentary, decentered, and fluid subjectivity of the postmodern world as well as of the need to find ways to represent and address this fragmentary subject. Accordingly, the self-reflexive texts look to create unity in a life that is perceived as increasingly disjointed.1

A notable surge in autobiographical forms could already be observed back in the 1980s and 1990s, which had an impact on documentary films: public history was written through the lens of the private and the associational.2 It is therefore unsurprising that autobiographies and other forms of personal documents would become an important source for rethinking history in former Soviet and socialist states as well. In Estonia and other Baltic states, grassroot organizations began collecting memories in the late 1980s. These memories were considered crucial in order to uncover the true history of ordinary people. The autobiographical accounts were used to rethink the national past and oppose official Soviet historiography. Recently, this phenomenon has assumed the different, more visual form of documentary films3 and TV series. These projects make use of footage from people’s home archives, and thus claim to be truthful depictions of the past.

In 2014, Estonian Public Broadcasting collected home movies and amateur films from people’s home archives and produced a TV documentary series, 8 MM LIFE [8 MM ELU] (2014–2015), based on the footage that was submitted. The 8 mm reels of silent, scarred, and scratched images mostly contain happy, personal accounts of episodes such as family day trips to car races or the zoo, holidays in the remote countryside or by the sea, visiting grandparents, milestones of children’s growing up, participating in Song Festivals, or protesting against the Soviet Union. They also show Estonian men telling the people to unite as a nation and fight for freedom. Despite the wide-ranging dates and contexts of these images, they can all be understood as evidence of the past events. In the TV series, the footage is reappropriated, and provided with context and narration. The series seems to bring the past closer to the audience, offering a glimpse of a world that has now changed and been left behind. It allows viewers not just to understand the past but to experience it, which is something that no written account can quite offer.4

The aim of this article is to explore how the era of late socialism5 is remembered in 8 MM LIFE. I discuss how the Soviet past in Estonia is reconstructed through the illusion of watching home movies together. I look at how “watching together”6 and interviewing the people shown in the series enables us to trace the memory dynamics of then and now, and consider how the framework of the series plays a role in reinterpreting the images, as watching the films evokes both shame and happiness. I analyze how the happiness inherent to the home movies produces ideals of the past and of the present, and how it intertwines with the narrative of the Soviet past as a dull, gray era of national rupture. Finally, I examine the ways in which gender, memory, and nation are reconstructed in the practices of reframing home movies and amateur films on TV.

My study is situated at the intersection between memory and gender studies. I use textual analysis to explore the depictions of home movies on TV, and apply the concept of personal cultural memory coined by José van Dijck, which she defines as “the acts and products of remembering in which individuals engage to make sense of their lives in relation to the lives of others and to their cultural context, situating themselves in time and place.”7 Home movies contain moments whose importance has been ingrained in people’s cultural consciousness. For example, they often depict rituals or symbolic highlights of people’s lives. The footage allows us to make sense of the world around us and to construct an idea of continuity between the (gendered) self and others.8 Hence, having people comment on their personal films on TV – thus changing the films’ original intended context – alters not only the personal act of remembering but also the cultural and national understanding of the past. In the series, the personal acts and products serve to reconstruct a coherent national self-image.

The two-season, 28-episode series was screened on Estonian Public Broadcasting in 2014 and 2015, airing on Channel 2 on Friday evenings before the news. The episodes could also be viewed on the website for at least 28 days, and are now available in the Estonian Public Broadcasting online archive.9 A Facebook page, where the episodes were advertised and clips were shown that attracted lots of likes, played an important role in the public reception of the series. Notably, an episode showing a clip that criticized the double burden of Soviet women was discussed in a feminist group on Facebook. Overall, while the series was well received, it did not provoke much public discussion, but did have the effect of encouraging more people to digitize their old films.10 There has not been any previous academic study of the series, nor much reflection in other media.11

The Cultural Form and Context of 8 MM LIFE

Estonian Public Broadcasting operates three TV stations, five radio stations, and a news website.12 It seeks to set itself apart from the commercial broadcasters and provide the audience with a cultural program with national content.813 Estonian Public Broadcasting is the only TV broadcaster to have produced historical documentaries and drama series about Estonia’s Soviet past, such as THINGS OF THE OLD TIME [VANA AJA ASJAD] (2004) and ESTONIAN SSR [EESTI NSV] (2010–2019).[14]14 In Estonian films and TV series, the era of late socialism has often been looked at with irony and laughter, ridiculing the Soviet system and seeing Estonians as separate from it. By featuring home movies and focusing on the lives of specific individuals, 8 MM LIFE seems to offer audiences a different kind of historical series, with more emotional, unmediated material. Kaidor Kahar,15 one of the series’ creators, was filmed by his uncle in the 1980s, and the idea for the series came out of his own footage.[16] 16

Estonian historiography about the last century relies to a notable extent on autobiographical texts. Collected life stories from the late 1980s onwards contributed to the Estonian historical discourse of the 1990s. In these accounts, the Soviet era was seen in terms of destruction of the nation’s natural way of life. At that time, the dominant narrative of Estonian history revolved around the concepts of “rupture” and “repression,” as well as “restoration of” and “continuity with” the prewar era. However, the turn of the millennium brought along changes in social memory, with more emphasis on the continuity of everyday life.17 This could be because the people who had grown up in the Soviet era and spent their most active years in the late socialist period began to “present themselves as socially competent individuals who had established normality in the era of late socialism,”18 whose stories needed to be heard. On the one hand, the dominant narrative of the past still upholds the idea of repression and resistance. On the other hand, the depoliticization of everyday life provides positive identification for the individuals who came of age during that period.

Although the series’ makers received home movies from various age cohorts, the vast majority of the invited studio guests were born between 1965 and 1980. These people were, with a few exceptions, unknown to the general public. They were usually depicted in the footage, and shared their memories about the films and about growing up in the Soviet era. Sometimes, the guests were families or parents with their now grown-up children, who talked, agreed, or had to be convinced by the other guest(s) about what life was like back then, thus bringing to the fore the act of generational remembering.

The series offered a platform for sharing audiovisual memories and stories from and about the era of late socialism in Estonia. The framework of the series and of the public broadcasting organization lends it a national undertone. However, the ways in which the past is communicated depend not only on national circumstances but also on transnational social and political situations.

Kirsti Jõesalu has pointed out that changes in political situations impact on the ways that different ethnic, social, and cultural groups interpret the past.19 The series was first aired in 2014, at the time when Russia had just occupied and annexed Crimea. Due to Estonia’s historical relationship with its neighbor Russia, sociopolitical changes in the country influence how the Soviet past is seen among the wider public and by researchers. It may have been the charged political atmosphere that prompted the makers of the series to stress that their intention was not to promote the idea that the Soviet era was idyllic, but rather to add a personal touch to history and see who we (as a nation) used to be and how we (as a nation) used to live.20 The series’ makers thus attempted to distance 8 MM LIFE from nostalgic interpretations of the Soviet past, which have sometimes been seen as a threat to democracy.21 I suggest that the reason for the series’ approach met with approval from audiences may have been due to the fact that in the Estonian cultural memory “home” used to be perceived as a sacred place, immune to the Soviet ideology, where Estonianness was preserved.22 However, that idea is now contested.23 Showing home movies on TV, as if peeking into someone’s home, seemed a safe way to talk about the Soviet past.

According to James Moran, the technology used for home movies emphasizes control and selection. By way of contrast with videos, the limited length of the reel and the impossibility of reshooting made home movie makers choose carefully what to film. The films thus steer clear of random moments and instead focus on ritualized events and special occasions. The absence of sound on 8 mm films further reinforces the “iconographic visual postures and tendencies to stereotyping.”24 The footage in 8 MM LIFE evokes warm, blissful memories. However, the films express both the filmmaker’s intentions and the material constraints of the equipment. While the footage of happy memories offers an escape from the everyday, the limits and costliness of the technology also reminds us that the films tend to depict the good lives of better-off people in Soviet Estonia.

Although there were well-established state-sponsored amateur film workshops in the Soviet Union, filmmaking remained expensive for individuals.25 In the series, the films are presented as found footage from people’s home archives, and not further contextualized within the history of amateur filmmaking in the Soviet Union. In Estonia, this history dates back to 1957, when the first amateur filmmaking club was opened. The amateur films were made for public screenings and for submission to competitions. The expectations for the films changed over the years. Early on, the focus was on the technical aspects of cinematography, while from the 1970s onwards the content of the films began to matter more. The films were often criticized for failing to conform to Soviet ideology, as they focused too much on artists and too little on workers’ experiences.26 8 MM LIFE also shows some amateur narrative films that deal (critically) with everyday issues in society and the workplace.27 However, the series focuses primarily on the point of view of the ordinary individual, thus leaving aside issues relating to Soviet institutions.

The films are accompanied by contemporary music and live commentary, either by studio guests,28 usually the people shown in the footage, or by professional TV presenter Tambet Tuisk.29 To further recreate the sense of the past, the studio is set up like a retro living room, complete with Soviet-era furniture and an old projector on the table.

This creates an illusion of watching the home movies together with the studio guests and viewers. Originally, when the films were watched together, those watching added voice and sound to the otherwise silent footage, opening up alternative ways of seeing: for instance, by pointing out omissions or things not visible on screen. Watching the films collectively was a special event, not only for the family but often for the whole community: the neighbors in the apartment building would be invited over, something that the series draws attention to. The smallness of Estonia played a role in the reception of the series, as viewers were more likely to have the feel-good moment of recognizing places. Together, the design of the studio and the series enhance the credibility of the footage and create a close connection to the (collective) past.

This immediate relation to the firsthand memories makes the audience feel they are seeing things the way they were seen back then. It also brings the “lived reality of the Soviet past” closer by focusing on singular moments in a particular individual’s life. In their study of Soviet photography, Oksana Sarkisova and Olga Shevchenko show that domestic photographs “represent a valuable resource for groups seeking to authenticate their perspectives on the past.” 30 I argue that the amateur films and home movies shown on TV function similarly – they validate and normalize the Soviet past by normalizing the life of the ordinary (Estonian) people, but not the Soviet Union.

“The happiness is all around us”

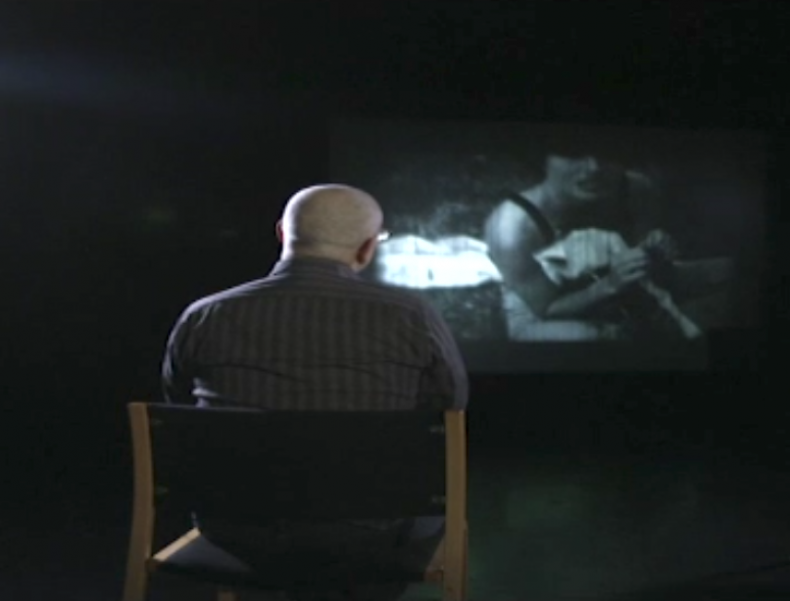

The series categorized the films thematically and included clips of diverse activities in each episode. There were moments of escaping the everyday and events with a national undertone, e.g. Estonia’s struggles to regain its independence and maintain its Estonianness. Some footage shows emblematic events from the late 1980s, such as the Song Festivals and the flying of the national flag in public.

These films are combined with patriotic songs and commentaries praising men for being hard-working, brave, and strong and standing up for the nation.31 Even though the footage seems to depict the past objectively, it presents a specific point of view and imposes a particular interpretation of the films. I argue that the undertone emphasizes the nation’s resilience in resisting the Soviet system and retaining its Estonianness. Since men – and not women – are often depicted as active participants in the historical processes and in regaining independence (waving the flags and speaking up in public), the national framework of the series takes a masculine form.

According to Meike Penkwitt, gender is a product of cultural memory and of the process of creating tradition. It results from iterative practices, through which memories become gendered.32 The questions of who remembers, what is remembered, and how, why, and for whom are therefore central to our inquiry. Keeping this in mind, home movies always imply an “I” – the person behind the camera – who crucially influences what is being remembered and for whom. The films sent to the studio were mainly shot by men (fathers, uncles, relatives, friends) and so carry a sense of male gaze. This is not to say that the series omits women: it does include women’s memories and voices; moreover, some of the footage shot by men was sent to the studio by women and also commented on by them. Still, it is the male narrator who has the power and voice to guide viewers through the “documents of the past,” hence reproducing male-centered historiography in Estonia.

According to Ann Rigney, aesthetics has the power to make stories more memorable and accessible.33 I suggest that the analogue aesthetics, with its imperfections and the “aura of human mistakes,” can prompt critical reflection on dominant memory practices. The footage in the series occasionally disrupts the prevalent understanding of the past, and is thus at odds with what has been seen and said about the films. One example of this is a clip of a family day trip to a small town. The voice-over says the town was decayed in the Soviet era, because it was dominated by the Russian Army.34 The footage, however, presents the town as harmonious and summery, and this impression remains intact in the recontextualization. By alternating between “Soviet” and “Russian,” the ethnic tensions are brought to the fore, as the latter is identified as “foreign” and “other.” At the same time, the commentary, through the othering, appeals to national unity.

Throughout the series, Russians are either omitted or represented as the invisible Other. The films were, with only one exception, shot by ethnic Estonians. The exception is the footage by Sergei Didyk, a Russian photographer who shot for a clothes factory in the 1970s. He is shown in the studio watching and commenting on his work,

which consists of erotic images of female models by the sea and at a picnic [Figure 5]. For him, this footage recalls good old times. He explains that they were all good friends and were having fun by the sea and at the picnic, which was to celebrate his graduation. Didyk seems happy to see the films and is astonished to see they are still sharp and in good condition.35 Showing him watching his films of models in the studio reinforces the male gaze of the episode and the series. Didyk also submitted a film reel that contained personal, happy moments from his private family life.36 Focusing on his professional rather than his private life further stresses the invisibility of Russians in everyday life. Moreover, showing footage of a Song Festival and patriotic songs after his clip brings to the fore the national undertone of the series’ version of history; this functions like a damage control mechanism, by presenting stories that do not subvert the coherent national self-image.

According to Neringa Klumbyte and Gulnaz Sharafutdinova, in the era of late socialism the state became more focused on pragmatic, day-to-day issues. It promoted private life and material consumption. It also encouraged creativity, individuality, and self-fulfillment among its citizens through education and various state-sponsored activities. Late socialism was thus a dynamic era where different values coexisted. The symbolic communist events mingled with nationalist ideals, the fascination of the imaginary West mingled with the hope of a fulfilling career in Soviet state institutions. These practices did not necessarily exist in opposition but instead synchronized with each other.37 The series depicts the era as more stable and as having more luxurious lifestyles than is normally assumed. It also shows footage of people conforming to the Soviet ideology, making it possible to identify layers of memory and see the attitudes of people commenting on the footage in the present.

The clash in remembering becomes evident in commentary on the films that show people conforming to the Soviet way of life. The people in the studio often deny that they did so, as this evokes shame today. One film shows the warm welcome given to a leading member of the Estonian Communist Party when he visited a small town in the 1970s. The people in the village are shown to be excited and looking forward to the guests: there are children wearing folk costumes and a woman with flowers. The man who shot the film claims that he and the other nine men from the town have no memory of the event having taken place at all. The footage is combined with music, in the style of an action film.38 The way the footage is presented undermines the popular narrative scheme of Estonian history according to which there is a clear divide between communists and “true” Estonians.

The (self-)stigmatization of conforming to communist ideology is further intensified in the commentaries on footage showing people who enjoyed privileges in the system and had access to things that were not available to everybody. For example, there is a clip of two women traveling to Egypt in 1974. The black and white footage shows long, panoramic shots of the land- and cityscapes in Egypt – the River Nile, the pyramids, the cities of Cairo and Alexandria. The people in the group are artists, writers, and workers. At the end of the footage, the travelers return home and give presents to their families. The series juxtaposes black and white shots of Egypt with images in color showing the women in the studio recalling the events. They feel the need to justify themselves, pointing out that their plans were plagued by uncertainties and that until the day of the trip no one could be sure whether they had secured their place.39 Referring to the stereotypical pattern of social relations (“you had to know the right people”) yet feeling the need to justify oneself reveals shame and denial of their own involvement in the Soviet system. In these cases, the past is constructed in opposition to the present. Even though people could have a pleasant life back then, the framework of the system is perceived as immoral. One way of interpreting this would be to see the Estonians as separate from the Soviet system in that the Estonians had to adjust to, and make the best of, the absurd and inevitable present.

However, the home movies in the series are mainly about blissful moments in the past. Reframed in the studio, the films and commentaries represent what the guests believe the recorded events show. The series, thus, not only reveals to the audience what people actually did, but what they wanted to do and what they now think they did.40 The home movies and commentaries represent conventions, ideals, and images of a happy life in both the past and present. The concept of happiness describes a state of being, but it is at the same time normative. Sara Ahmed points out that it is associated with some, and not other, life choices and objects. For her, happiness consists in being oriented toward a promised good life, and the judgment about things that promise happiness is culturally made before we encounter them. Happiness is situated within normative social institutions such as heteronormative marriage and family, gender norms, and employment, thus concealing the inequalities of who gets to live a good life.41

By showing films of harmonious family events – day trips, get-togethers, intimate encounters, weddings, and even wedding nights – and then combining the images with shots of children’s smiles and calm, soothing music, 8 MM LIFE reveals the fantasies of a good life. One of the clips shown in the series is footage of a couple’s wedding night. The footage is accompanied by smooth saxophone music, and the camera shows a woman undressing and later making the bed, underscoring the romantic atmosphere. The camera zooms in on the woman’s breasts and the hand behind the camera touches her naked body; the interaction between the individuals in front of and behind the camera emphasizes the sensual intimacy of the scene. The footage ends with glimpses of the couple’s children and the mother smiling to the camera while putting groceries into the fridge.42 On the one hand, this framing creates a deeply sensuous experience. On the other hand, the footage not only shows the harmonious family within the privacy of their apartment, but also reveals the performativity of gender and reconstitutes traditional gender roles.

The images of blissful and joyous moments in the series do not simply represent the past as idyllic, but also paint the present as better and more liberal than the past by showing images that were taboo in the Soviet era. There is footage of a young couple spending time in the countryside, who go swimming nude.43 This footage disrupts the general perception of the Soviet era in Estonia on at least two levels. First, the TV host says that viewers will now see images that would not have made it to the TV screen back in the day. This creates a contrast with the past; the present is depicted as more liberal than the strict Soviet body politics. Yet the people in the studio feel the need to justify themselves, saying that they were always looking for secluded places to practice nudity. This highlights the taboos of both then and now. Second, the footage shows the people’s happiness, providing a form of self-representation and constructing identity through their family history. On a broader level, it celebrates the individuals for being able to lead a happy life under the repressive circumstances.

Conclusion

One of the objectives of this article has been to explore how the era of late socialism is remembered in the Estonian TV series 8 MM LIFE. The series reappropriated old home movies from people’s home archives to give a glimpse of past events and past happiness. The people in the studio both observe the past and engage with it. Studio guests often feel the need to justify themselves or feel shame when they are shown conforming with the communists and/or adapting to the Soviet system, as this subverts the hegemonic memory work that sees Estonians as victims of the repressive system. Even though the films function as if they were direct windows onto the past, the images are sometimes at odds with what is said in the studio, thus bringing the memory work to the fore. The films from the era of late socialism may paint a harmonious picture of history, but the studio comments occasionally bring the harmony into question, since the national narrative rejects seeing the era of late socialism in more positive terms.

Another, related aim was to analyze how the personal experiences compiled in the series create a sense of national commonality and unity. The framework of the series and of Estonian Public Broadcasting adds a national undertone. The individual happy encounters are intertwined with the national narrative of suffering and repression, and reconstruct a discourse of a happy national subject that conformed to the system only to the extent needed to have a decent standard of living. Moreover, the images of nudity, and other content that was presumably prohibited back in the Soviet era, are presented in order to depict the present as more liberal. The narrative structure of the series is masculine inasmuch as it stresses men’s role in fighting for independence. The blissfulness, however, creates an impression of a happy national subject. In summary: the TV series 8 MM LIFE reconstructs the national narrative through personalized stories. The first-person accounts form parts of the bigger picture, and hence create a seemingly more truthful narrative.

The visual footage and the commentaries in the studio are rhetorically powerful. The series and the technology of 8 mm film may limit what we see and hear, but they do not limit how we think about the films.

- 1Laura Rascaroli, The Personal Camera: Subjective Cinema and the Essay Film (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014), 2–4.

- 2Michael Renov, The Subject of Documentary (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), 110.

- 3 Similar projects have emerged in other Eastern European countries too. For instance, in Latvia the filmmakers Romualds Pipars and Maija Selecka collected home movies and amateur footage shot between 1950 and 1980 in order to produce a full-length documentary, THE FLIPSIDE OF THE COIN (2008), about personal experiences under Soviet rule. The film juxtaposes home movies with official Soviet cinema reels, revealing the different realities of official ideology and lived experience.

- 4Jaimie Baron, The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History (New York: Routledge, 2014), 1.

- 5This era extends, roughly speaking, from the 1960s to the 1980s (i.e. the period following Stalinism and preceding Perestroika). See Kirsti Jõesalu, Dynamics and Tensions of Remembrance in Post-Soviet Estonia: Late Socialism in the Making (Tartu: Tartu University Press, 2017). Although technology, visual ideologies, and society itself changed considerably in the course of this period, I will not focus on the differences between films from different parts of the period. Instead, I study the films from the perspective of memory studies and look at how people relate to their old films in general; the difference that I am concerned with lies in between generations.

- 6 I was inspired by Martha Langford’s concept of “speaking the album,” which she coined while studying photo albums in a museum, with a focus on memory, orality, and the stories people told about their albums when the album’s environment of remembrance was radically changed. The home movies have been moved from homes to TV, hence changing their viewing environment. See Martha Langford, “Speaking the Album: An Application of the Oral-Photography Framework,” in Locating Memory: Photographic Acts, ed. Anette Kuhn and Kirsten Emiko McAllister (New York: Berghahn Books, 2008), 224.

- 7

José van Dijck, “Mediated Memories: Personal Cultural Memory as Object of Cultural Analysis,” Journal of Media and Cultural Studies 18, no. 2 (June 2004): 262.

- 8Van Dijck, “Mediated,” 263–4.

- 9Margus Sikk, 8 MM LIFE, Estonian Public Broadcasting, TV series (Tallinn, 2014–2015), https://arhiiv.err.ee/seeria/8-mm-elu/elu/31

- 10I rely here on my own observations and investigations, as well as on the comments by people on various platforms concerning the digitization of their films. Interestingly, on these platforms people never seem to disagree with the things said in the series. There are a few comments pointing out that the footage is of their home neighborhood or asking for advice about digitizing their films. Oddly, nonfiction TV programs, especially documentaries, are rarely reviewed or discussed in Estonian media. Neither are there any statistics available about how many people watched this particular series, either at the time of first broadcast or in the online archive. I therefore do not attempt to make generalizations about the wider reception, but only about my own.

- 11The present article is based on previous research carried out for my MA thesis, in which I also studied the series. Liis Jõhvik, Homemade Histories on TV: Gender and Memory in the Estonian TV Series 8 MM LIFE (2014–2015), master’s thesis (Vienna: University of Vienna, 2017).

- 12Eesti Rahvusringhääling [Estonian Public Broadcasting], accessed July 10, 2019, https://www.err.ee.

- 13Hagi Šein, “Rahvusringhäälingu kuvandi maastik: taustauuringud ja muud hüpoteesid,” Memokraat, February 10, 2010, http://memokraat.ee/2010/02/rahvusringhaalingu-kuvandiraamistik-taustat…

- 14For example, in 2004 Estonian Public Broadcasting aired a series, THINGS OF THE OLD TIME [VANA AJA ASJAD], that featured archival amateur footage and newsreels showing everyday life and things from the period 1960–1985. There was also a popular comedy series, ESTONIAN SSR [EESTI NSV] (2010–2019), that focused on fictional characters living in a communal apartment in the 1980s.

- 15The writer and producer of the series, Kaidor Kahar, was born in Estonia in 1980. He completed a degree in television scriptwriting at Tallinn University in 2002. He has been working for Estonian Public Broadcasting since 2003 as a TV presenter, producer, and direct

- 16“‘8 mm elu’ – tänu ajastu kroonikutele,” Maaleht, October 9, 2014, https://maaleht.delfi.ee/news/lehelood/koik/8-mm-elu-tanu-ajastu-krooni….

- 17Ene Kõresaar, “Life Story as Cultural Memory: Making and Mediating Baltic Socialism since 1989,” in Baltic Socialism Remembered: Memory and Life Story since 1989, ed. Ene Kõresaar (London: Routledge, 2018), 13.

- 18Uku Lember, “Temporal horizons in two generations of Russian–Estonian families during late socialism,” in Generations in Estonia: Contemporary Perspectives on Turbulent Times, ed. Raili Nugin, Anu Kannike, and Maaris Raudsepp (Tartu: Tartu University Press, 2016), 162–163.

- 19Jõesalu, Dynamics and Tensions of Remembrance, 11.

- 20“Tänu ajastu kroonikutele.”

- 21Jõesalu, Dynamics and Tensions of Remembrance, 13.

- 22Epp Annus, Soviet Postcolonial Studies: A View from the Western Borderlands (London: Routledge, 2018), 204–210.

- 23Andres Kurg argues that the Soviet subjectivity was formed not only in workplaces and other public institutions but through cultural engagement and socialization in all spheres of society, including the home (through home decoration, etc.). Andres Kurg, Boundary Disruptions: Late-Soviet Transformations in Art, Space and Subjectivity in Tallinn 1968–1979, doctoral thesis (Tallinn: Estonian Academy of Arts, 2014), 74.

- 24James M. Moran, There’s No Place Like Home Video (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), 41.

- 25Maria Vinogradova, “Between the State and the Kino: Amateur Film Workshops in the Soviet Union,” Studies in European Cinema 8, no. 3 (2011): 212.

- 26“Kokkuvõte amatööride töödest,” Rahva Hääl, January 1, 1963; L. Varik, “Meie amatöörfilm,” Rahva Hääl, May 19, 1973.

- 27For example, the series shows a clip of an amateur film from 1978 that criticizes Soviet society and family life. This clip juxtaposes footage of a child being fed by her mother and the mother doing other household chores with footage of the father queuing to buy alcohol and later drinking with his friends. This film is the only one of its kind; the rest of the footage is more cheerful. Parties with food and alcohol are included, but never really present a critique of the way of life. 8 MM LIFE, 1/2014.

- 28The series incorporates footage of both celebrities (politicians, artists, musicians) and “ordinary” people. Even though there are films by people from very different walks of life (doctors, shop assistants, engineers, taxi drivers, people from the countryside, etc.), not much attention is paid to social background. The most prominent person depicted in the series is the composer Arvo Pärt. He is shown in his apartment in 1965 painting the walls of his soundproof room and later partying with his friends and colleagues. The footage is accompanied by his music.

- 29Tambet Tuisk (born in 1976) is a stage and film actor, whose roles have included Schnaps in the Estonian–German coproduction THE POLLI DIARIES (2010) and several recent parts in TV dramas such as PANK (Tallinn 2018). “Tambet Tuisk,” Estonian Film database, accessed July 8, 2019, https://www.efis.ee/et/inimesed/id/3524/.

- 30Oksana Sarkisova and Olga Shevchenko, “Soviet Past in Domestic Photography: Events, Evidence, Erasure,” in Double Exposure: Memory and Photography, ed. Olga Shevchenko (London: Transaction Publishers, 2014), 148.

- 318 MM LIFE, 11/2014.

- 32Meike Penkwitt, “Erinnern und Geschlecht,” Freiburger Frauen Studien 16 (2006): 1.

- 33Ann Rigney, “Cultural Memory Studies: Mediation, Narrative, and the Aesthetic,” in International Handbook of Memory Studies, ed. Anna Lisa Tota and Trever Hagen (London: Routledge, 2016), 69.

- 348 MM LIFE, 6/2015.

- 358 MM LIFE, 2/2015.

- 36Sergei Didyk also sent reels to the studio containing moments from his family life, such as holidays with the children. There was also a clip of the same picnic with an image of Didyk cross-dressing and undressing on the beach in front of the models. But these clips were not shown in the series; the series instead preferred to show naked women.

- 37Neringa Klumbyte and Gulnaz Sharafutdinova, “Introduction: What Was Late Socialism?” in Soviet Society in the Era of Late Socialism, 1964–1985, ed. Neringa Klumbyte and Gulnaz Sharafutdinova (Plymouth: Lexington Books, 2013), 15; see also Jõesalu, Dynamics and Tensions of Remembrance, 22.

- 388 MM LIFE, 11/2015.

- 398 MM LIFE, 10/2014.

- 40Alessandro Portelli, “What Makes Oral History Different,” in The Oral History Reader, ed. Robert Perks and Alistair Thomson (London: Routledge, 1998), 67.

- 41Sara Ahmed, “Sociable Happiness,” Emotion, Space and Society 1 (2008): 12.

- 428 MM LIFE, 2/2014.

- 438 MM LIFE, 7/2014.

“‘8 mm elu’ – tänu ajastu kroonikutele.” Maaleht, October 9, 2014. https://maaleht.delfi.ee/news/lehelood/koik/8-mm-elu-tanu-ajastu-krooni….

Ahmed, Sara. “Sociable Happiness.” Emotion, Space and Society 1 (2008): 10–13.

Annus, Epp. Soviet Postcolonial Studies: A View from the Western Borderlands. London: Routledge, 2018.

Baron, Jaimie. The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History. New York: Routledge, 2014.

van Dijck, José. “Mediated Memories: Personal Cultural Memory as Object of Cultural Analysis.” Journal of Media and Cultural Studies 18, no. 2 (June 2004): 261–77.

Jõesalu, Kirsti. Dynamics and Tensions of Remembrance in Post-Soviet Estonia: Late Socialism in the Making. Tartu: Tartu University Press, 2017.

Jõhvik, Liis. Homemade Histories on TV: Gender and Memory in the Estonian TV Series 8 MM LIFE (2014–2015). Master’s thesis. Vienna: University of Vienna, 2017.

Klumbyte, Neringa, and Gulnaz Sharafutdinova. “Introduction: What Was Late Socialism?” In Soviet Society in the Era of Late Socialism, 1964–1985, edited by Neringa Klumbyte and Gulnaz Sharafutdinova, 1–14. Plymouth: Lexington Books, 2013.

“Kokkuvõte amatööride töödest.” Rahva Hääl, January 1, 1963.

Kõresaar, Ene. “Life Story as Cultural Memory: Making and Mediating Baltic Socialism since 1989.” In Baltic Socialism Remembered: Memory and Life Story since 1989, edited by Ene Kõresaar, 1–19. London: Routledge, 2018.

Kurg, Andres. Boundary Disruptions: Late-Soviet Transformations in Art, Space and Subjectivity in Tallinn 1968–1979. Doctoral thesis. Tallinn: Estonian Academy of Arts, 2014.

Langford, Martha. “Speaking the Album: An Application of the Oral-Photography Framework.” In Locating Memory: Photographic Acts, edited by Anette Kuhn and Kirsten Emiko McAllister, 223–46. New York: Berghahn Books, 2008.

Lember, Uku. “Temporal Horizons in Two Generations of Russian–Estonian Families during Late Socialism.” In Generations in Estonia: Contemporary Perspectives on Turbulent Times, edited by Raili Nugin, Anu Kannike, and Maaris Raudsepp, 159–87. Tartu: Tartu University Press, 2016.

Moran, James M. There’s No Place Like Home Video. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

Penkwitt, Meike. “Erinnern und Geschlecht.” Freiburger Frauen Studien 16 (2006): 1–26.

Portelli, Alessandra. “What Makes Oral History Different.” In The Oral History Reader, edited by Robert Perks and Alistair Thomson, 32–42. London: Routledge, 1998.

Rascaroli, Laura. The Personal Camera: Subjective Cinema and the Essay Film. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

Renov, Michael. The Subject of Documentary. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

Rigney, Ann. “Cultural Memory Studies. Mediation, Narrative, and the Aesthetic.” In International Handbook of Memory Studies, edited by Anna Lisa Tota and Trever Hagen, 65–79. London: Routledge, 2016.

Sarkisova, Oksana and Olga Shevchenko. “Soviet Past in Domestic Photography: Events, Evidence, Erasure.” In Double Exposure: Memory and Photography, edited by Olga Shevchenko, 147–74. London: Transaction Publishers, 2014.

Šein, Hagi. “Rahvusringhäälingu kuvandi maastik: taustauuringud ja muud hüpoteesid.” Memokraat, February 10, 2010. http://memokraat.ee/2010/02/rahvusringhaalingu-kuvandiraamistik-taustat….

Varik, L. “Meie amatöörfilm.” Rahva Hääl, May 19, 1973.

Vinogradova, Maria. “Between the State and the Kino: Amateur Film Workshops in the Soviet Union.” Studies in European Cinema 8, no. 3 (2011), 211–225.