Workings of Postmemory in Twenty-First Century Argentina

Cecilia Kang’s PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME (2023) and HIJO MAYOR (2017–in progress)

Table of Contents

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Introduction

Beginning in the second half of the nineteenth century, massive transatlantic human displacement from European countries to the Americas shaped twentieth-century Argentine cultural scenes ranging from literature, music, and sport to cinema as well as the politics and economy of the country.1 During the latter half of the twentieth century, migration and cultural exchanges within the Americas became more pronounced than overseas ones while transpacific migration also started to weigh in on the Argentine demography.2 The South Korean community in Argentina began forming during this relatively recent wave of migration after the first government-sanctioned migration from South Korea in 1965. The second, also government-sanctioned and now large-scale migration started around 1985. South Korean migrants have consisted of less than 0.1 percent of the current Argentine population since the late 1990s.3 Cecilia Kang, born in Argentina in 1985 as part of this ethnic minority group, has been making films featuring stories of people around her, while navigating challenges common to contemporary Argentine filmmakers in their early careers under the current economic climate of the country. Kang is the first woman director from the South Korean community in Argentina with professional training from the country’s film schools.4 Due to her ethnicity, Kang faces several unique challenges and opportunities in the national and international film industries. This essay focuses on her two projects, PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME (Argentina 2023) and HIJO MAYOR (Argentina in development since 2017). PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME is a feature-length documentary on remembering the atrocities of war and imperialism during the 1930s and 1940s through testimonies by women survivors of WWII, known as ‘Comfort Women.’ HIJO MAYOR is a feature film based on Kang’s family’s migration and settlement in Buenos Aires since the mid-1980s. By examining these two projects, this essay will present an example of transpacific postmemories emerging in contemporary Argentine society. This will show what discourses and resources are available in the current film industries when an Argentine filmmaker like Kang strives to depict her postmemory, which she hopes will become collective and cultural in nature after dissemination.5

Postmemory in Twenty-First Century Argentina

Postmemory is a useful concept for understanding cinematic approaches taken in PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME and HIJO MAYOR. In these projects, Kang traces other people’s memories based on testimonies, personal stories, and old pictures. This concept has been widely used since its conception in the early 1990s to explicate artistic and literary representations of the Holocaust. According to Marianne Hirsch, who coined this term when analyzing Maus (1980–1911) by Art Spiegelman, postmemory is a form of memory that does not come from first-hand experience, which gives the word its prefix ‘post,’ showing its mediated nature. The original, often traumatic, experience comes from an earlier generation, transmitted by “stories, images, and behaviors.”6 This concept has also been used to analyze Argentine films based on memories of traumatic events of state violence experienced by filmmakers’ family members or acquaintances. The best-known examples in this regard would be Albertina Carri’s LOS RUBIOS (AR 2003)7 and Benjamín Ávila’s INFANCIA CLANDESTINA (2011).8 There have been critiques that question the suitability of postmemory for analyzing Argentine films by the second generation of the “disappeared (desaparecidos), especially for interpreting innovative documentaries produced in the early 2000s like LOS RUBIOS.9 Similar critiques may apply to this essay. However, I use the concept in its broadest sense to generally refer to the mediated memories that pass down through generations, regardless of their means, and end up being constitutive of one’s identity.

The original experience that Kang represents in HIJO MAYOR is based on her family members’ migration from South Korea to Argentina. Kang began working on this feature-length project in 2017. According to the film’s original script, which has suffered substantial changes due to limited funding sources, the experience is narrated in reverse chronological order, starting from her own memory during her teenage years in early 2000s Argentina, then, her mother’s in mid-1980s South Korea before Kang was born, and lastly her father’s in mid-1980s Paraguay. In PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME, the mediated experience stems from the systematic and state-run sexual violence committed during the 1930s and 1940s. In this hybrid feature-length documentary, Kang does not directly represent or exhibit the atrocities of colonialism and war. Instead, the film stresses the mediated nature of the stories presented to the audience with the camera following the daily life of a contemporary Argentine girl in the Korean community in Buenos Aires, who was asked to recite testimonies by the director.

Even though Argentine audiences are being exposed to scenes that have been or are becoming part of contemporary Argentine society since the 1980s, the two films present very different images from those of other Argentine films set during the same time period. The narratives that the two films introduce may sound familiar to common Argentine moviegoers due to their main thematic concerns: migration and war atrocities. However, at the same time, the cinematic representation of these narratives may seem very foreign to most audiences from any region due to its transpacific perspective that deviates from the dominant transatlantic narratives and representations common in Latin American films set in Buenos Aires. Now we have Cecilia Kang’s Buenos Aires and her mapping of the global connection between Latin America and other continents that came into existence mainly during the second half of the twentieth century. This global connection gave birth to postmemories in contemporary Argentine society, ranging from domestic and war violence to patriarchal structures of human displacement that PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME and HIJO MAYOR address.

Transpacific Memories and Transatlantic National Culture

PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME is a documentary about Melanie, a girl in her twenties in the Korean community in Argentina who experiences an unexpected effect upon the reading of written testimonies narrated by comfort women, Asian girls and women who were forced into sexual slavery by the imperial Japanese army during the 1930s and 1940s. Melanie prepares for the role in her daily life, practicing with her mother, friend, and mentor. Through this experience, Melanie sees how people around her react to her performance and what kind of different personal memories the testimony evokes in each person. However, after days of practice, when she has a chance to share her reading experience and performance with a larger audience at an open microphone event in her city, Melanie cannot read even a word from the testimony. She seems to fear potential misunderstandings and misinterpretations by the audience who do not know the horrific history she wants to share. Around the incident at the open-mic event,

Melanie dives deeper to reconnect with this dark history. She decides to travel to South Korea for her research. She visits the House of Sharing in the city of Gyeonggi, an organization that serves as a museum and home for some of the survivors. If, from their testimonies, these women were able to transfer all that pain to her, perhaps she can help to shed light on the untold stories back in her own country, where so little of this is known, even in the Korean community there.10

During the second half of the film set in South Korea, Melanie meets her older brother and a friend who are also from the Korean community in Argentina and now planning to settle in South Korea. After visiting the House of Sharing, Melanie participates in the Wednesday Demonstration, a weekly protest to seek justice for the Comfort Women issues. This time, she speaks up for justice not only for war victims but also for victims of domestic violence, reminding the audience of Melanie’s conversation with her mother in the earlier sequence, where the mother talks to her daughter about her past as a victim of domestic violence. The following sequence starts with a piece of pensive non-diegetic music during which Melanie appears to spend time by herself. After meeting her brother and his partner, in the last sequence, Melanie has a “bad, lovely girl” tattooed on her shoulder which she says shows her character.

The title, PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME, makes it clear that the documentary is anchored in Argentine cultural memory by using part of a line from a poem by Alejandra Pizarnik (1936–1972), a widely read Argentine poet. During her lifetime, Pizarnik was a prolific poet and writer and left works of poetry and other writings such as diaries, short stories, and short novels. After dying young at the age of 36 by suicide, she became a mythic figure as an “enfant terrible” in Argentine literature.11 Pizarnik was born in 1936 in Argentina to Jewish immigrant parents who migrated from a city currently located in Western Ukraine. With self-esteem issues and having a stutter, she had a difficult childhood, which might have affected her decision to change her given name, Flora, by adopting the name Alejandra as a teenager. The original line of the poem, Árbol de Diana (1962), is:

13

explicar con palabras de este mundo

que partió de mí un barco llevándome12

(to explain with words from this world

that a boat left from within me, taking me away)13

The line describes a figurative image of a person who has left behind her past self and feels something is permanently missing. It also suggests a literal image of a person leaving behind her homeland for an unknown territory. By leaving, she also leaves behind part of her own self. The boat carries part of her away from the other part, which also belongs to her. For Pizarnik, who was born to a migrant family in Argentina in the 1930s, “this world” was a place where lots of people have memories of a boat.14 This is where the Argentine audience can see a sign of the convergence of transatlantic and transpacific postmemories expressed by women artists of the second generation.

Julio Chávez (b. 1956), a renowned Argentine actor and filmmaker, plays an important role as an interviewer and mentor in PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME to have the Argentine audience relate to the main character, Melanie.15 In the sequence where Melanie recites one of the survivors’ testimonies before him,16 the Argentine audience can readily identify themselves with the familiar Argentine actor who listens to an unfamiliar story and whose eyes brim with tears. According to Kang, this sequence was much criticized for disrupting the film’s rather tranquil style and rhythm that centers on a girl’s everyday life by introducing a national movie star. Despite criticism, Julio Chávez broaches critical points or challenges that Melanie has to cope with when sharing transpacific experiences in Argentine society, where transatlantic memories are dominant. First, he compares the testimony, recited by Melanie, to Holocaust survivors, which is an expected reaction from anyone who grew up watching Hollywood films on the Holocaust. As Aleida Assmann aptly points out, over the last five decades, throughout the proliferation of cultural products and institutional supports, “the reference to the Holocaust in the shape of a global icon and cultural symbol is easily disseminated around the world and used for all kinds of purposes.”17 However, the Argentine context that Kang invokes through Pizarnik’s poem and the conversation with Julio Chávez is not a de-contextualized or de-territorialized reference as both Pizarnik and Chávez identify themselves as of Jewish descent. With the largest Jewish population in the Southern Hemisphere, Argentina is a member state of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, formerly the Task Force for International Cooperation on Holocaust Education, Remembrance, and Research, or ITF. For Melanie, there exists a huge discrepancy in her education regarding war crimes during WWII. As an Argentine citizen, she learned much about what happened to her fellow citizens of European descent, but as a citizen of Korean descent, she was not taught about an important part of WWII, which she thinks might account for what she, her family and friends, and other acquaintances have experienced as Asian women in Buenos Aires.

Julio Chávez acknowledges Melanie’s stereotypical view towards Koreans as concentrated in the garment and textile industry. As Melanie shares her deep impression during her first trip to South Korea when she saw Koreans working in different fields to her astonishment, Julio Chávez chimes in by mentioning that her experience disrupted the caste that exists in Argentine society. Among other South Korean migrants, those who arrived in Buenos Aires in the 1980s filled the vacancy in the garment industry left by Jewish people fleeing from the anti-Semitic Argentine military regime between 1976 and 1983, especially after the Falkland Conflict, or Guerra de las Malvinas, in 1982.18 As part of East Asian communities in the Americas, Korean Argentines in Argentina are not free from the relatively recent stereotypical images of East Asian migrants as hardworking ‘model minorities’ created by mainstream North American media and cultural products, nor from the generalization of personalities tied to one’s occupation. In the perception of common Argentines from Buenos Aires, los chinos (the Chinese and Taiwanese), run grocery stores; los coreanos (the Koreans), sell clothes; and los japoneses (the Japanese), who used to be laundrymen, are now quite well assimilated into Argentine society and distinguish themselves from other East Asian migrant groups. According to Junyoung Verónica Kim, these imaginaries of East Asian migrants have been shaped also by the existing hierarchy between countries. In short, among East Asian countries, Japan belongs to the advanced and civilized ‘First World,’ while South Korea is still working to catch up.19 Migrants and their descendants from China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, which outnumber those from South Korea and Japan, also have complex and diversified identities and lie beyond the scope of this essay. However, one thing is clear: filmmakers of East Asian descent in Argentine society have increased the visibility of their communities not only through their work but also under the influence of the changing perceptions about those countries within contemporary Argentine society. As pointed out by the contributors of Imagining Asia in the Americas (2016), those perceptions are closely tied to Eurocentric imaginaries of world geography, each country’s current economic and cultural influence on the global market, and whether that influence is perceived by the U.S. and European media on positive or negative terms. With Kang’s cinematic intervention, Argentine audiences are invited to ponder the historical foundation of national imaginaries and stereotypes that permeate all levels of society with a transpacific perspective alongside their existing knowledge of transatlantic discourses.

With all these external factors at play, PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME and HIJO MAYOR evoke the fact that Argentina along with other Southern Cone countries has been one of the final destinations for migrants for more than a century.20 As part of the global film community, Argentine filmmakers of Kang’s generation are well aware of the recent challenges of climate change, which gave birth to the concept of ‘climate refugees’ as well as more traditional political and economic issues, all of which cause unsought-for human displacement.21 Before this recent political redefinition of ‘refugee’ became legally established and culturally settled, on February 24, 2022, with the Russian invasion of Ukraine, films representing or harking back to wars of the past centuries, mostly those waged in European countries that caused transatlantic migration, obtained room for allegorical interpretation.

PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME belongs to this group of films reminiscent of war atrocities and postmemories held by later generations, but with a transpacific focus. In this sense, regarding its aesthetics and approach, the film has more affinity with DRIVE MY CAR (JP 2021) by Ryusuke Hamaguchi than with other feature films or documentaries that address the issues of comfort women. In Hamaguchi’s film, a stage actor and director who is in mourning for his late wife accepts a directing job in another city, Hiroshima, and works with staff and actors to stage a play. Due to the pandemic in 2020, Hamaguchi had to change the location from Busan to Hiroshima, which granted the film unintended meanings of 1) cinematic mourning for collective memories against Japanese imperialism over characters’ home countries and 2) a criticism against Russian irredentism as a new form of imperialism, which began three months after the film’s release in the US on November 24, 2021.22 It is telling that both Kang’s documentary and Hamaguchi’s feature film focus on the practice or rehearsal of mourning in a multilingual setting rather than seeking excellence or consummation of a piece of work. In DRIVE MY CAR, actresses and actors from different countries rehearse in Hiroshima to stage Uncle Vanya (1899) by Anton Chekhov (1860–1904). Most of them hold postmemories regarding Japanese imperialism. In this historical backdrop, performing a play together in their respective languages earns an ethical and political meaning.23 PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME is in three languages: Spanish, Korean, and English. English is used as a link language not only for the audience with subtitles but also for Melanie, the main character of the film, when she visits Korea. Both films value the time that a process of mourning and learning requires. What cinema does here is give rhythm and style to its repetition.

Cuts, Changes, and Deletions in HIJO MAYOR, the Earlier Version of PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME, and Other Projects

MI ÚLTIMO FRACASO (AR 2016), Kang’s first feature-length documentary on women in the South Korean community in Buenos Aires, was screened at various film festivals in 2016. The following year Kang began working on her first fiction film based on her family’s migration, HIJO MAYOR, and finished writing the script in 2020. While searching for funding sources to film HIJO MAYOR, in 2019, Kang embarked on another project, which became PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME (2023). When these three projects about human displacement were conceived and carried out, the metaphoric configuration of migrants in society as zombies, aliens, monsters, animals, or ghosts had already been common in contemporary cinematic representations. In films from the 1990s to 2010s Americas, mostly set in large US cities, this narrative strategy was mainly used to depict those who migrated due to economic reasons, internal conflicts, or climate change rather than due to international war affairs. Thus, the accelerated globalization over the last several decades and its backlash turned the interregional migration of working-class people into a new symbol of an unwanted, traumatizing experience to be shunned by citizens in societies receiving newcomers. Following this movement of globalized capital that affects the labor market at national and international levels, most South Korean migrants came to Argentina not as refugees but due to economic reasons as a potential workforce.

HIJO MAYOR explores migration taken for economic improvement and shows the challenges that many families face worldwide as they settle, with a focus on a minority ethnic group, which is rarely the subject of this process within films. According to its original script, HIJO MAYOR requires filming in three different countries, Argentina, South Korea, and Paraguay. The film tells the family stories of Lila, the protagonist of the first part and alter ego of the director Cecilia Kang. The stories are framed within the historical context made by a protocol on Korean investment immigration between the Korean and Argentine governments around 1985, which attracted Korean immigrants from Paraguay and Bolivia to Argentina and gave those who had already settled in the city the opportunity to create a larger community. By reconstructing specific and personal moments that each character lived, the film presents those moments in a sensuous and cinematic way without presenting to the viewer the aforementioned historical context. According to Kang’s own words on HIJO MAYOR, she is constructing emotional maps (cartografía emocional) based on subjective memories that are shown in pictures and objects, that is to say, lived memories that can hardly be chronicled in a rigorously historical manner. However, from a bird’s eye view, their displacement was driven by the global history of the twentieth century that shaped the modern history of the two Koreas. This, in turn, cannot be explained without the major historical events during the so-called long twentieth century such as the nineteenth-century imperialism and competition between hegemonic powers, and the Cold War regimes, to name only a few.

MINARI (USA 2020) by Lee Isaac Chung can be a North American counterpart of Kang’s project in this regard, which proves how hard it can be to make a film like HIJO MAYOR in Argentina. MINARI is a low-budget film produced in a single location outside Tulsa, Oklahoma with a twenty-five-day shoot.24 Still the film cost two million USD, which is an inconceivable amount of money, considering the budget limitations that all Argentine filmmakers are experiencing with the dire economic situation in the country.25 As of May 2023, HIJO MAYOR was expected to be shot in October 2023, starting from locations in South Korea, with funding from three countries: Argentina, France, and South Korea. However, the film was not selected at the final stage of the competition for funding from the Korean Film Council, which was announced in June 2023; in the same year, the INCAA, a state-funded agency that supports cinema and audiovisual arts in Argentina, reduced its entire budget and cannot offer fund for Kang’s project at the moment. Despite such challenges with funding sources, which led to removing the Korean part of the original script, HIJO MAYOR won an award in March 2025 at the 37th Festival Cinélatino de Toulouse (Latin Cinema Festival of Toulouse). As of April 2025, it is in its post-production stage, awaiting release in 2025 or 2026.

PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME had shots and sequences that were not included in the final version, which could have changed or expanded the film’s focus. During her stay in Singapore between 2020 and 2021, Kang filmed places in the country, which served as “comfort stations” during the Japanese occupation of Singapore between 1942 and 1945.26 After due consideration, the sequence was removed so the sole focus on Melanie’s experience could help the audience follow the narrative and build emotion without distraction. Kang herself had not known about comfort women issues before she traveled to South Korea as an adult in 2013. In contrast, there had been such contentious political debates on the matter in South Korea, Japan, and Japanese and South Korean communities in California as documented in SHUSENJO: THE MAIN BATTLEGROUND OF THE COMFORT WOMEN (USA 2018) by Miki Dezaki (b. 1983), a Japanese American filmmaker. Consequently, she began thinking about the ways she could tell this story from her position as a Korean Argentine, not as an expert on the subject matter.27 This resulted in Melanie’s journey from Argentina to South Korea occurring within her family ties. She has other reasons to visit South Korea such as to meet her brother, his girlfriend, and her friend from Argentina. According to Rodrigo Piedra, “[Kang] takes distance from the historical record documentary and, instead, seeks to connect the subject to the local Korean community through a fake documentary (se aleja del documental de registro histórico y, en cambio, busca conectar el caso con la colectividad coreana local a través de un falso documental).”28 It is hard to draw a line between fiction and documentary with PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME. For Kang, it must have been an impossible project to make a period film about comfort women for practical and ethical reasons. Rather, Kang chose to represent the reading experience of a testimony, whose effects ripple through people around Melanie, which I argue makes Kang’s film relatable to a larger audience beyond Argentina and South Korea.

Given this socio-economic milieu in which Kang worked on her three feature-length films, it is not surprising Kang has collaborated with filmmakers from different continents to realize decolonial cinematic projects. Making a film that is non-commercial and does not fit into any national film industry is never an easy task. The importance of Lita Stantic, or Élida Stantic’s, roles as a producer for the New Argentine cinema is well known along with the support or investment other European producers and filmmakers have made in the Argentine film industry. For many film directors in their early careers who do not have their Lita Stantic, these networks form at international film festivals. Kang is no exception. So far, Argentina, France, Germany, and South Korea have supported her projects, all of which have their own cinematic tradition, industry, and audience. Be it national or international, in the film industry, creators must negotiate constantly with domestic capital represented as a national audience or with global capital, almost always synonymous with the Western world, to actualize their decolonial visions. Kang’s trajectory as a filmmaker illustrates this point well. As a filmmaker, Kang also has been on other directors’ projects. There are two international projects in which Kang was involved. One was to be shot in Mozambique. This project could not be carried out due to the pandemic and other reasons that are not hard to imagine. Mozambique is not a wealthy country and is a lot worse off than Argentina. Meanwhile, Kang has been working with Yeo Siew Hua (b. 1985), a director and writer from Singapore, on his projects since they met in 2019 at a residency program in Berlin. Yeo Siew Hua is taking a path that many directors who had commercial success in their careers have taken. He makes commercial TV series and films, for example, for HBO Asia, and with the money he earns, he then makes his own work. Kang’s delayed collaboration with filmmakers in Mozambique and continued work with those from Singapore show how the colonial differences keep creating inequality in representation and exemplify one of the many difficulties in making a so-called “south-south” collaboration successful. If the Mozambique project had been realized, we could have a very different type of transatlantic memories, or postmemories, from a region that used to be part of the Portuguese empire and is now a member of the Commonwealth of Nations without having been a colony of the British empire.

Conclusion

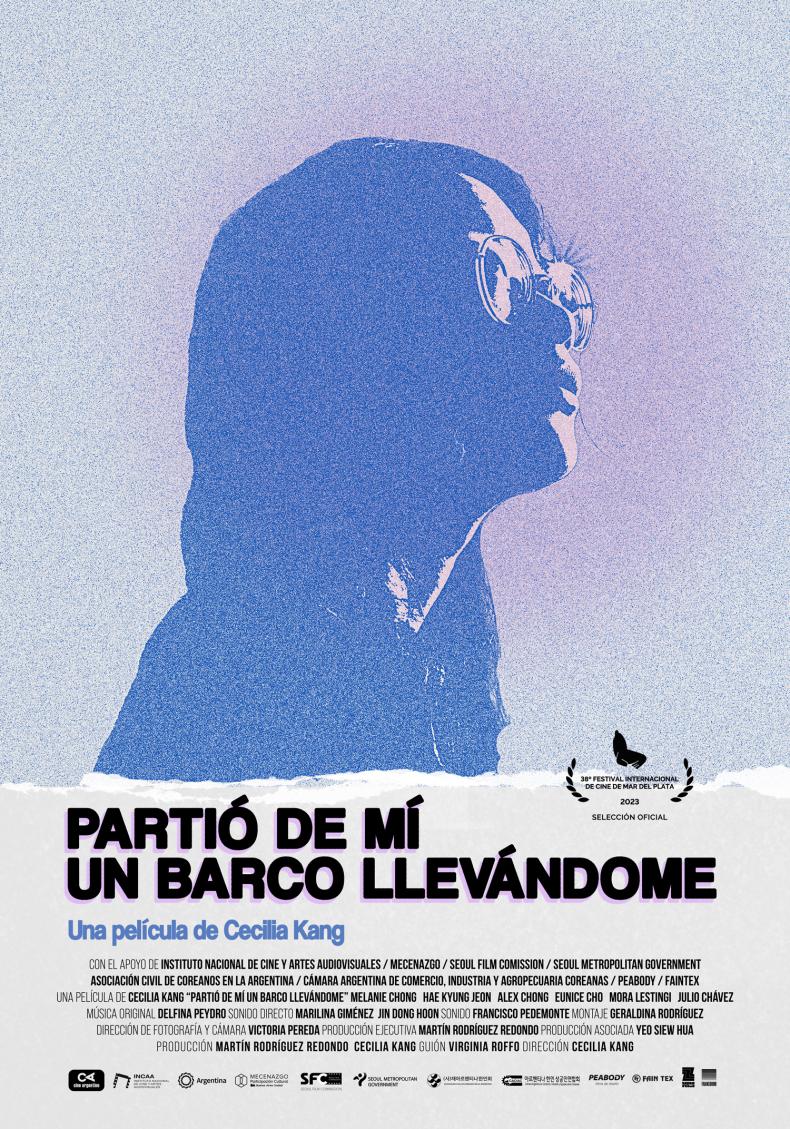

Kang’s trajectory as a filmmaker presents 1) common challenges that filmmakers in their early careers face and 2) possible breakthroughs found in the globalized film industry and its ideology, which shapes the range of each project’s audience and sometimes even the film’s aesthetics. So far, PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME has drawn more attention than her other two feature-length projects: MI ÚLTIMO FRACASO, which premiered in 2016, and HIJO MAYOR, which began in 2017 and is now, as of April 2025, in post-production and expected to be released by 2026 due to a limited budget that came from several different countries. PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME premiered on November 7, 2023, at the 38th Mar del Plata International Film Festival and won two awards out of six awards of international competition29: Special Jury Award (Premio Astor Piazzolla Especial del Jurado) and People’s Choice Award (Premio del Público).30 According to the jury’s comment,31 the jury award was given to Kang:

For building a powerful link between a search for identity, a family history, and violence against women in Korea during the Japanese War.

(Por la construcción de un potente vínculo entre una búsqueda de identidad, una historia familiar y la violencia hacia las mujeres en Corea durante la guerra japonesa.)32

The comment could have been more historically precise and ideologically broad if it had mentioned, instead of invoking a hackneyed ethnic binary, that the violence occurred mainly during WWII and was driven by the imperial fever that dates back to the late nineteenth century. All in all, it seems that Kang succeeded in articulating an unexpected but systemic interrelation between war crimes and the current gender issues within the Korean community by making the audience sympathize with Melanie, the main character of the film, who represents a small but important part of a younger generation in Argentine society. Kang says the People’s Choice Award was the best she could hope to receive as a filmmaker. In Argentina, it is common for commercially released films to be dubbed in Spanish, which is not an option for Kang’s film as it would mar the aesthetics of the film. Partly due to this, before the festival, Kang’s documentary had little expectation for release in theaters. With the awards, as of December 2023, the film is expected to be in theaters in Argentina in early 2024. With the success of PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME, which is now available online (filmin.es), Argentine audiences with transatlantic postmemories will have a chance to become more aware of the presence of people around them holding transpacific postmemories. Since its release in July 2024, the film has not only met Argentine audiences but has also reached Uruguay, Colombia, Peru, Spain, the Canary Islands, Germany, and Russia. If Kang’s projects can be distributed beyond Argentina to reach a wider audience, they will be cinematic examples for ongoing comparative discourses, which this essay cannot cover, regarding 1) capitalism, colonialism, and the recent trend of ‘return to Western’ and women’s views in films from the Americas; 2) imperialism, war, and women’s narratives; and 3) ‘latecomer communities’ and the issues of the ‘anthropological gaze’ in world cinema.

- 1

For European emigration between 1848 and 1875, see Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Capital (New York: Vintage Books, 1996), 193–207. For the influence of the California Gold Rush (1848–1855) in Latin American countries, see Tulio Halperin Donghi, Historia contemporánea de América Latina (Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1990), 216–219. For further information about the immigration to Argentina during the period of concern, see Blanca Sánchez-Alonso, “Making sense of immigration policy: Argentina, 1870–1930,” The Economic History Review 66, no. 2 (2013): 601–627, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2012.00671.x. For the influence of the European opera in the Argentine culture during these decades, see Gonzalo Aguilar, Episodios cosmopolitas en la cultura argentina (Buenos Aires: Santiago Arcos Editor, 2009), 37–57.

- 2

Maia Jachimowicz, “Argentina: A New Era of Migration and Migration Policy,” The Online Journal of the Migration Policy Institute (February 2006), https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/argentina-new-era-migration-and-migration-policy.

- 3

Carolina Mera, “Los migrantes coreanos en la industria textil de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Inserción económica e identidades urbanas.” Revue Européenne Des Migrations Internationales 28, no. 4 (2013): 67–87, https://doi.org/10.4000/remi.6221.

- 4

For Asian directors and the representation of Asian communities in Argentina, see Lucía Rud, “Representaciones de las migraciones y diásporas de Asia del Este en el audiovisual argentino,” Nuevo Mundo, Mundos Nuevos (2020), https://doi.org/10.4000/nuevomundo.80888.

- 5

For the definition of cultural memory that differs from social and political memory see, Aleida Assmann, “Memory, Individual and Collective,” in The Oxford Handbook of Contextual Political Analysis, ed. Robert E. Goodin and Charles Tilly (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 220–221.

- 6

Marianne Hirsch, “Postmemory,” accessed December 13, 2023, https://postmemory.net/.

- 7

Gabriela Nouzeilles, “Postmemory Cinema and the Future of the past in Albertina Carri's Los Rubios,” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies: Travesia 14, no. 3 (2005): 263–278, https://doi.org/10.1080/13569320500382500.

- 8

Sarah Thomas, “Rupture and Reparation: Postmemory, the Child Seer and Graphic Violence in Infancia clandestina (Benjamín Ávila, 2012),” Studies in Spanish & Latin-American Cinemas 12, no. 3, (September 2015): 235–254, https://doi.org/10.1386/slac.12.3.235_1.

- 9

For further detail, see Verónica Garibotto, Rethinking Testimonial Cinema in Postdictatorship Argentina: Beyond Memory Fatigue (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019), 116–128.

- 10

From the original, unedited synopsis by Cecilia Kang and Virginia Roffo. For the official synopsis, see “Partió de mí un barco llevándome,” see “Partió de mí un barco llevándome,” Wikipedia, accessed August 5, 2025, https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parti%C3%B3_de_m%C3%AD_un_barco_llev%C3%A1ndome.

- 11

Patricia Venti, La escritura invisible: El discurso autobiográfico en Alejandra Pizarnik (Barcelona: Anthropos Editorial, 2008), 10.

- 12

Alejandra Pizarnik, Árbol De Diana (Buenos Aires: Sur, 1962), 23.

- 13

Another version of the English translation by Yvette Siegert reads: “to explain with words of this world / that a ship set sail from me and took me with her.” Alejandra Pizarnik, Diana’s Tree, trans. Yvette Siegert (Brooklyn: Ugly Duckling Press, 2014), 15.

- 14

For further information about Pizarnik’s identity as the second generation of a Jewish migrant family, see Venti, La escritura invisible, 162–172.

- 15

This is not the first case that Kang’s film features well-known Argentine actors or actresses. Her first short, QUE VIVA EL AGUA (AR 2011), stars Rosario Bléfari (1965–2020) and Susana Pampín (b. 1964).

- 16

The testimony assigned to Melanie is from Hwang Geum Joo (1922–2013), who was active in seeking justice for war victims since 1992. “Cries of the Victims (피해자들의 외침),” War & Women’s Human Right Museum, accessed August 5, 2025, https://womenandwarmuseum.net/96/?bmode=view&idx=18187742.

- 17

Aleida Assmann, “The Holocaust – a Global Memory? Extensions and Limits of a New Memory Community,” in Memory in a Global Age: Discourses, Practices and Trajectories, ed. Aleida Assmann and Sebastian Conrad (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 114.

- 18

Consequently, many South Koreans in textile and garment industries in Buenos Aires work and live in competition and collaboration with Jewish people. See Ki-Hong Han, “Inmigración a Argentina, 45 años,” Weekly Kunghayng, September 26, 2022, https://m.weekly.khan.co.kr/view.html?med_id=weekly&artid=202209161450411&code=117#c2b.

- 19

Junyoung Verónica Kim, “Disrupting the ‘White Myth’: Korean Immigration to Buenos Aires and National Imaginaries,” in Imagining Asia in the Americas, ed. Zelideth María Rivas and Debbie Lee-Distefano (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2016), 41–42.

- 20

To address this century-long issues and recent challenges in migration, in 2019, the III Symposium of Southern Cone Studies, a section of the Latin American Studies Association, was held in Buenos Aires under the title of “Cuerpos en peligro: Minorias y migrantes (Bodies in Danger: Minorities and Migrants).”

- 21

During the first two decades of the twenty-first century, the tragic consequences of climate change became the most sought topic not only in global film communities but in all cultural products as epitomized in the title of a documentary premiered at the Sundance Film Festival: CLIMATE REFUGEES (USA 2010). This newly coined term “climate refugees” is a political term to raise awareness regarding the human rights of climate migrants, who do not hold traditional refugee status in any country yet.

- 22

Seungjoo Lee, “Ética y política en festivales de cine: Retos nacionales y vínculos transnacionales,” K-cine y k-drama desbordados, ed. Woo Suk-kyun, Bárbara Bavoleo, and Choi Jin-ok (Santiago de Chile: Ril Editores, 2024).

- 23

In the film, Japanese, Korean, Indonesian, German, Tagalog, Cantonese, Mandarin, Malaysian, and Korean Sign Language are spoken, and English is used as a link language. Nina Li Coomes, “Drive My Car Pushes the Limit of Language,” The Atlantic, March 5, 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2022/03/drive-my-car-hamaguchi-language/626561/.

- 24

Mia Galuppo, “Making of ‘Minari’: How Lee Isaac Chung Created a Unique American Story Rarely Seen Onscreen,” The Hollywood Reporter, January 21, 2021, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/making-of-minari-how-lee-isaac-chung-created-a-unique-american-story-rarely-seen-onscreen-4117397/.

- 25

As of December 2023, Kang expects 81,000 euros as the estimated budget for HIJO MAYOR, which is less than one-twentieth of MINARI’s.

- 26

Kevin Blackburn, “The Comfort Women of Singapore during the Japanese Occupation: A Dark Heritage Trail,” transcript of speech delivered at the National Museum of Singapore, February 22, 2019, https://www.nhb.gov.sg/nationalmuseum/-/media/nms2017/documents/publication-and-resources/historiasg-lecture-1-22-feb-2019--kevin-blackburn-transcript.pdf.

- 27

Pablo Mc Fly, “VideoEntrevista a Cecilia Kang – Directora de Partió de mí un barco llevándome,” November 18, 2023, interview, 11:38, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o6YCyvekJ2I.

- 28

Rodrigo Piedra, “Crítica de Partió de mí un barco llevándome: Mirar lo delicado en un mundo de tanta violencia,” Indie Hoy, November 10, 2023, https://indiehoy.com/cine/critica-de-partio-de-mi-un-barco-llevandome-mirar-lo-delicado-en-un-mundo-de-tanta-violencia/.

- 29

Following are the other four films awarded of international competition at the festival: Best Feature Film-KINRA (Peru) by Marco Panatonic; Best Director-Laura Basombío for LAS ALMAS (AR); Best Performance-Sara Summa in ARTHUR & DIANA (DE); Best Screenplay-Shane Atkinson for LAROY (USA). Overall, this list reflects the general tendencies observed in recent international film festivals such as the cinematic representation of indigenous people (KINRA and LAS ALMAS), social issues related to migration either from country to city or between countries (KINRA and PARTIÓ DE MÍ UN BARCO LLEVÁNDOME), and the return of the Western films (LAROY).

- 30

Kang also received another two ‘independent’ awards at the festival: Best Argentine Documentary (Mejor documental argentino de todas las Competencias) from ADN – Asociación de Directores y Productores de Cine Documental Independiente de Argentina and Best Film (Mejor película de la Competencia Internacional) SIGNIS – Asociación Católica Mundial para la Comunicación. See, “Conocé las películas premiadas del Festival Internacional de Cine Mar del Plata,” Buenos Airece Ciudad, accessed August 5, 2025, https://buenosaires.gob.ar/noticias/conoce-las-peliculas-premiadas-del-festival-internacional-de-cine-mar-del-plata.

- 31

The members of the jury are Prano Bailey-Bond (Wales), Celina Murga (Argentina), Mimi Plauché (US), Tara Schembori (Paraguay), and Charles Tesson (France).

- 32

“Premios Oficiales Mar 38,” accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.mardelplatafilmfest.com/39/es/noticia/premios-oficiales.

Aguilar, Gonzalo. Episodios cosmopolitas en la cultura argentina. Buenos Aires: Santiago Arcos Editor, 2009.

Assmann, Aleida. “Memory, Individual and Collective.” In The Oxford Handbook of Contextual Political Analysis, edited by Robert E. Goodin and Charles Tilly, 210–224. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Assmann, Aleida. “The Holocaust – a Global Memory? Extensions and Limits of a New Memory Community.” In Memory in a Global Age: Discourses, Practices and Trajectories, edited by Aleida Assmann and Sebastian Conrad, 97–117. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Blackburn, Kevin. “The Comfort Women of Singapore during the Japanese Occupation: A Dark Heritage Trail.” Transcript of speech delivered at the National Museum of Singapore, February 22, 2019. https://www.nhb.gov.sg/nationalmuseum/-/media/nms2017/documents/publication-and-resources/historiasg-lecture-1-22-feb-2019--kevin-blackburn-transcript.pdf.

Coomes, Nina Li. “Drive My Car Pushes the Limit of Language.” The Atlantic, March 5, 2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2022/03/drive-my-car-hamaguchi-language/626561/.

De los Rios Herández, Isabela. “‘Enough Already!’: The Challenges of Restorative Justice in War Crimes.” Harvard International Review, August 31, 2023. https://hir.harvard.edu/enough-already-the-challenges-of-restorative-justice-in-war-crimes/.

Galuppo, Mina. “Making of ‘Minari’: How Lee Isaac Chung Created a Unique American Story Rarely Seen Onscreen.” The Hollywood Reporter, January 21, 2021. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/making-of-minari-how-lee-isaac-chung-created-a-unique-american-story-rarely-seen-onscreen-4117397/.

Garibotto. Verónica. Rethinking Testimonial Cinema in Postdictatorship Argentina: Beyond Memory Fatigue. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019.

Halperin Donghi, Tulio. Historia contemporánea de América Latina. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1990.

Han, Ki-Hong. “Inmigración a Argentina, 45 años.” Weekly Kunghayng, September 26, 2022. https://m.weekly.khan.co.kr/view.html?med_id=weekly&artid=202209161450411&code=117#c2b.

Hirsch, Marianne. “Postmemory.” Accessed December 13, 2023. https://postmemory.net/.

Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Capital. New York: Vintage Books, 1996.

Jachimowicz, Maia. “Argentina: A New Era of Migration and Migration Policy.” The Online Journal of the Migration Policy Institute, (February 2006). https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/argentina-new-era-migration-and-migration-policy.

Kim, Junyoung Verónica. “Disrupting the ‘White Myth’: Korean Immigration to Buenos Aires and National Imaginaries.” In Imagining Asia in the Americas, edited by Zelideth María Rivas and Debbie Lee-Distefano, 34–55. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2016.

Lee, Seungjoo. “Ética y política en festivales de cine: Retos nacionales y vínculos transnacionales.” In K-cine y k-drama desbordados, edited by Woo Suk-kyun, Bárbara Bavoleo, and Choi Jin-ok. Santiago de Chile: Ril Editores, 2024.

Mc Fly, Pablo. “VideoEntrevista a Cecilia Kang – Directora de Partió de mí un barco llevándome.” November 18, 2023. Interview, 11:38. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o6YCyvekJ2I.

Mera, Carolina. “Los migrantes coreanos en la industria textil de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. inserción económica e identidades urbanas.” Revue Européenne Des Migrations Internationales 28, no. 4 (2013): 67–87. https://doi.org/10.4000/remi.6221.

Nouzeilles, Gabriela. “Postmemory Cinema and the Future of the Past in Albertina Carri’s Los Rubios.” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies: Travesia 14, no. 3 (2005): 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569320500382500.

“Partió de mí un barco llevándome,” Wikipedia, accessed August 5, 2025, https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parti%C3%B3_de_m%C3%AD_un_barco_llev%C3%A1ndome.

Piedra, Rodrigo. “Crítica de Partió de mí un barco llevándome: Mirar lo delicado en un mundo de tanta violencia.” Indie Hoy, November 10, 2023. https://indiehoy.com/cine/critica-de-partio-de-mi-un-barco-llevandome-mirar-lo-delicado-en-un-mundo-de-tanta-violencia/.

Pizarnik, Alejandra. Árbol de Diana. Buenos Aires: Sur, 1962.

Pizarnik, Alejandra. Diana’s Tree. Translated by Yvette Siegert. Brooklyn: Ugly Duckling Press, 2014.

Rud, Lucía. “Representaciones de las migraciones y diásporas de Asia del Este en el audiovisual argentino.” Nuevo Mundo, Mundos Nuevos (2020). https://doi.org/10.4000/nuevomundo.80888.

Sánchez-Alonso, Blanca. “Making Sense of Immigration Policy: Argentina, 1870–1930.” The Economic History Review 66, no. 2 (2013): 601–627. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2012.00671.x.

Thomas, Sarah. “Rupture and Reparation: Postmemory, the Child Seer and Graphic Violence in Infancia clandestina (Benjamín Ávila, 2012).” Studies in Spanish & Latin-American Cinemas 12, no. 3, (September 2015): 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1386/slac.12.3.235_1.

Venti, Patricia. La escritura invisible: El discurso autobiográfico en Alejandra Pizarnik. Barcelona: Anthropos Editorial, 2008.

War & Women’s Human Right Museum. “Cries of the victims (피해자들의 외침).” Accessed August 5, 2025. https://womenandwarmuseum.net/96/?bmode=view&idx=18187742.

38º Festival Internacional de Cine de Mar del Plata. “Premios Independientes.” Accessed August 5, 2025. https://www.mardelplatafilmfest.com/39/es/noticia/premios-oficiales.